This is a translation of “Cleachtaí agus Fotharaga na Nollag”.

The hustle and bustle of Christmas today derives primarily from the impact of the Victorian world and of American commercialism: The Christmas tree, for example, and the turkey, were not features of the tradition of Christmas in the past. The Irish, of course, had their own customs linked to the celebration of the Feast. They cleaned up their houses, both inside and outside, whitewashing the walls with lime, putting fresh sand on the floor, and placing a lighted candle in the window. It was, after all a time of renewal, a leaving behind of the depths of darkness and a movement towards a new period of light.

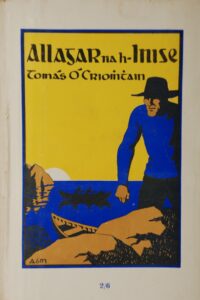

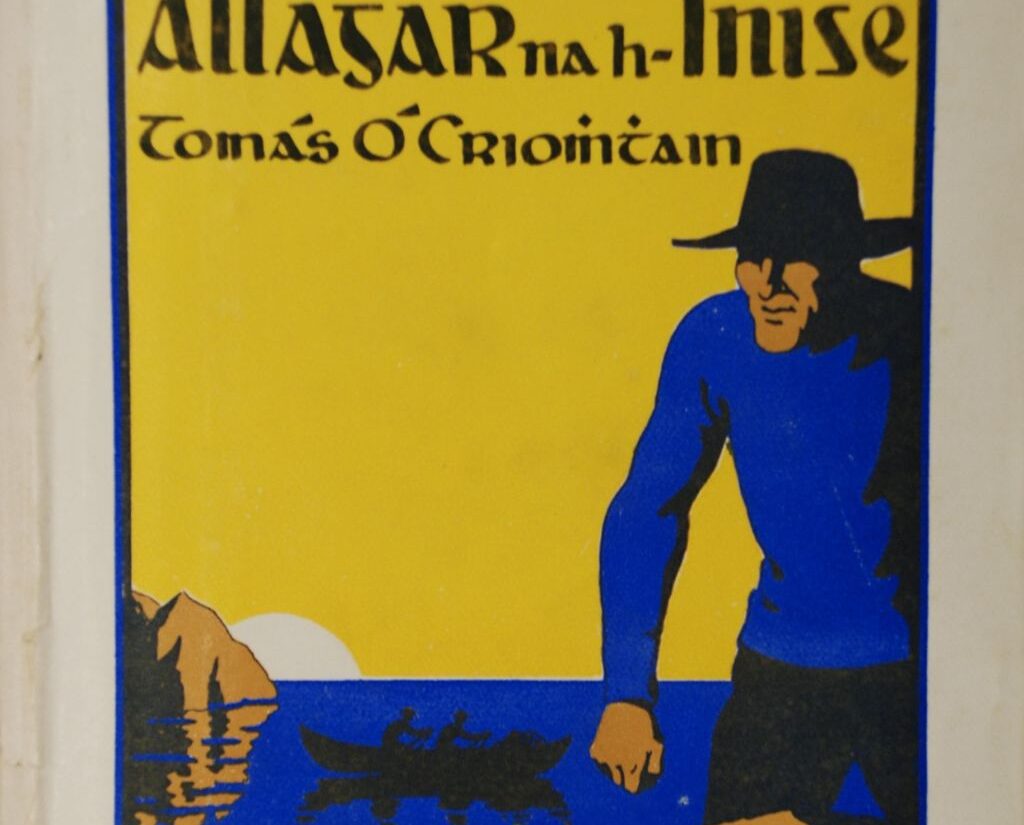

And here in the south of the country, there was, as well, as part of the tradition, the Wren Boys. Tomás Ó Criomhthain has a description of this custom in an account that he wrote in Allagar na hInise (1928, 1977). Six young lads burst through the door towards him, “Each with a stout stick in their hand, a mask on their face, a change of clothes, and their speech muffled as they pranced up and down the floor. They had the form of a small bird on the end of a pole and one of them was pointing towards it.” This was the St Stephen’s Day custom, the day after Christmas.

There is a valuable collection of these traditions in the collection of the Irish Folklore Commission which is available on microfilm in UCC Library.

But life and values have changed since then. Change is, of course, a central part of culture. Certain aspects are set aside, and new elements brought in. Often, it is not clear what is at the root of such change. But in the case of Christmas it seems that it is primarily the materialism of the modern era that is driving the change. The Gaels of Ireland called Christmas night, “An Oíche Bheannaithe” or “The Blessed Night” and it is clear that the notion of “Blessed” is now gone, or at the very least, going and the night might be more accurately described as “The Night of profit” or the “Night of the Huckster”.

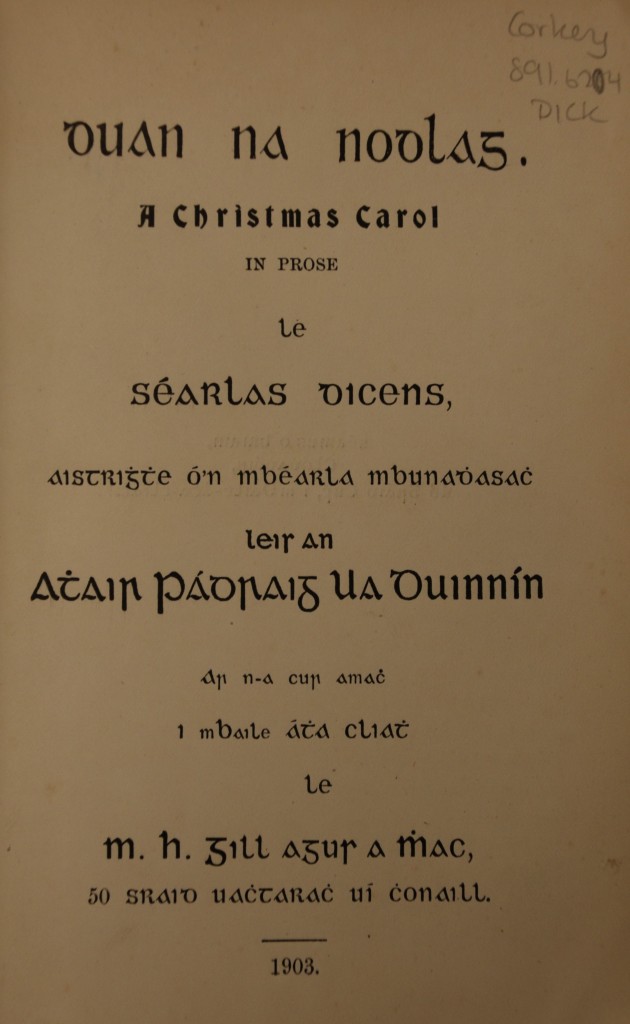

There is a fine example of the Victorian ideal in the novel by Dickens, The Christmas Carol and it is very interesting that this is one of the first modern translations that was made available in the early years of the Gaelic revival. Fr. Pádraig Ó Duinnín published Duan na Nodlag in 1903, a short novel for the modern era of the Irish language. Ó Duinnín said the following about it:

“A Christmas Carol,” by Charles Dickens, is here presented to the reader in an Irish dress. For the selection of this work my friend, Mr H.J. Gill, is responsible, and there are many considerations to commend his choice. Keen satire and melting pathos, well known characteristics of Dickens, are fairly represented in this piece, and these qualities are calculated to commend him to Irish readers. Besides, the sympathy with the poor and outcast, with which this story abounds, will ensure it a welcome in many an Irish home. If modern Irish is to strike deep literary roots it must be cultivated in the domain of translation from other modern languages, and a better selection could hardly be made to begin with than Dickens.” (Ó Duinnín, 1903)

A copy of Duan na Nodlag is held in UCC Library here in Cork.

References

Dicens, Séarlas. Duan na Nodlag. Translated from English by Fr. Pádraig Ua Duinnín. Baile Átha Cliath M.H. Gill 1903.

Ó Criomhtháin, Tomás. Allagar na hInise. Extracts from a diary. Edited by An Seabhac. Baile Átha Cliath: Ó Fallamhain i gcomhar le hOifig an tSoláthair, 1928.