The Early History of Printing and Philanthropy in Cork

- Elaine Harrington

- March 13, 2018

The River-side welcomes Garret Cahill’s guest post on the early history of printing and philanthropy in Cork.

2018 marks European Year of Cultural Heritage and, relatedly, the Jubilee of Johannes Gutenberg (c.1440-1468), the father of European printing, who died 550 years ago last February 3rd. Though the famous Bible he printed dates from 1455, it was some decades before the new technology was diffused throughout Europe. The first text to be printed in English, The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, was produced by William Caxton in either Bruges or Ghent in 1473. Three years later he established a press at Westminster in London, bringing out many literary works, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and the first English translation of Aesop’s Fables.

Notwithstanding the successes of Caxton and others in England, printing was slow to spread to Ireland; though a ready market certainly existed for imported books. It was not until 1551 that Humphrey Powell established the first printing press in Dublin, having received £20 sterling from the Privy Council ‘towards his setting up in Ireland’ as royal printer. Developments in provincial Ireland took longer still, but by the 1640s presses had been established in Waterford, Kilkenny and Cork. Of course, collections of books had existed in Cork well before this date, and the beginnings of a diocesan library can be traced back to 1629 when Richard Owen, Prebendary of Kilnaglory, gave £20 towards its construction – the predecessor of the St Fin Barre’s Cathedral collection now held in the Boole Library. But the introduction of a printing press to Cork is largely related to the political situation in the mid-seventeenth century.

The Catholic rebellion of 1641 had left Cork as an island of Protestant control, under the military leadership of Murrough O’Brien, Lord Inchiquin, known colloquially as ‘Muchadh na dTóiteán’, in reference to the extensive burnings of properties carried out under his jurisdiction. The rest of the county was largely in rebel hands under the nominal command of Donough MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry. Perhaps understandably, William Chappel, Bishop of Cork and Ross since 1638, fled the rebellion and landed at Milford Haven on 27th December, later lamenting the loss of his library of rare books and manuscripts on their separate passage to Minehead. In Chappel’s absence, the chapter of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral elected Edward Worth to the vacant Deanery of Cork in March of 1642. This was officially a royal appointment, but the growing strains between Charles I in England and the increasingly hostile Long Parliament meant that when the king appointed his own Dean, Henry Hall, the cathedral chapter refused to accept him, and Worth remained in his position. In March of 1645, Worth preached at the funeral of Richard Boyle, the Archbishop of Tuam, cousin of the Earl of Cork of the same name. Boyle had died in Cork, his former diocese, on 19th March, and was buried, as he had arranged, in a chapel of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral. The occasion of the funeral sermon is noteworthy for two reasons: firstly, it establishes Worth’s close connections with the influential Boyle family; but secondly, his sermon was printed in Cork, marking the first recorded instance of such printing in this city. Unfortunately, no copy of the sermon appears to survive, though the indefatigable Richard Caulfield quotes briefly from it in his Annals of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, noting that Worth stated “while this Prelate sat in the See of Cork, he repaired more ruinous churches, and consecrated more new ones, than any other Bishop in that age” (28).

possibly after Sir Anthony van Dyck

oil on canvas, based on a work of circa 1640. National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG 893.

The contested nature of parliamentary and royal power at this time, placed civic and ecclesiastical authorities in Cork in a difficult position, but by July of 1644, the Munster Protestants had aligned themselves with parliament. Dean Worth evidently was of the same view, for in March of 1646 he travelled to London on behalf of Lord Broghill, closely aligned with the parliamentary cause, and younger brother of Richard Boyle, second Earl of Cork. When Lord Inchiquin – fresh from his victory over confederate forces at Knocknanuss in north Cork – declared for the royalists in the spring of 1648, Worth declined to join those clergymen in Munster who had signed an address supporting him. Inchiquin’s defection, however, prompted the second essay from the printing press of Cork: The Declaration and Ingagement of the Protestant Army in the Province of Mounster, and shortly afterwards a retort: The Answer of the Comittee of Estates of Parliament of Scotland To the desires sent to them from the Lord Inchiquin, both from 1648. These were issued without a printer’s name, but “to be sold at Roche’s building, without South Gate”. As the fluctuating fortunes of king and parliament played out in arrivals and departures from Cork, a sequence of partisan publications were issued, with one – Eikon Basilike: The Portraicture of His Sacred Majesty in His Solitudes and Sufferings being not merely the most substantial of publications hitherto (at 320 pages), but also the first to identify a printer by name. This was Peter de Pienne, the first printer known in Waterford. He had evidently relocated to Cork by 1648, but given the royalist nature of his publication, he perhaps thought it prudent to return to the south-east when Cork was taken by Cromwellian forces in 1649. Nevertheless, he later printed material for the Commonwealth, including Monarchy: No Creature of God’s Making, so we can conclude his allegiances were purely commercial !

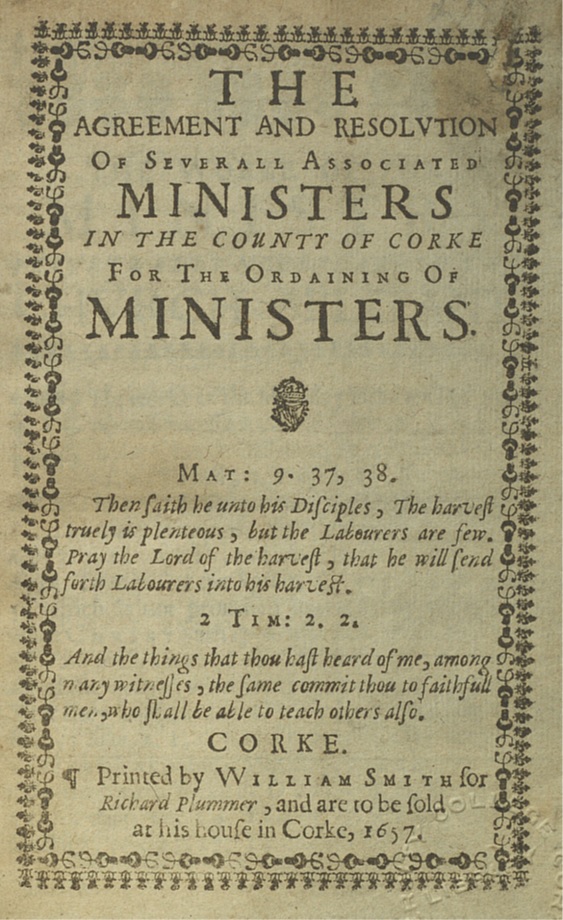

The Cromwellian occupation of the city, and the religiously dissenting tenor of many in the army, also created problems for Edward Worth. In 1649-50, many of the Cork clergy were ejected from their posts, and the role of Dean was abolished. However, the continued patronage of the ‘Old Protestant’ community in Munster, particularly the Boyles, ensured Worth was given replacement livings, and by 1753, Worth apparently felt sufficiently secure to preach two sermons opposing the views of Dr John Harding, formerly a Church of Ireland cleric, and now a Baptist preacher. Scripture Evidence for Baptizing the Infants of Covenanters Produced at Cork in two Sermons is given as “printed for T. Taylor widow, and are to be sold at her shop in Cork” – the only reference to this bookseller. The arrival of Henry Cromwell, son of the Lord Protector, as de facto governor of Ireland in 1755 also proved of assistance in advancing Worth’s career; both men shared moderating views on the need to find a new religious settlement which would combat the rise of Baptists and other dissenters in Ireland. To this end, Worth had initiated a weekly lecture for clergymen in Cork, to be attended only by those who had been ordained by a bishop or through Presbyterianism. This eventually led to a declaration of principles entitled The Agreement and Resolution of Severall Associated Ministers in the County of Corke for the Ordaining of Ministers. It was printed in 1657 by William Smith at Cork, and does not ascribe authorship. However, Worth’s hand is surely in evidence, and the copy held by the National Library in Dublin has manuscript notes that attribute the text to him.

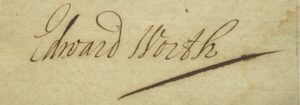

This work is also the only locally-printed text held in the Boole Library from the 17th century. The copy held in Special Collections has ‘Edward Worth’ elegantly inscribed on the final page:

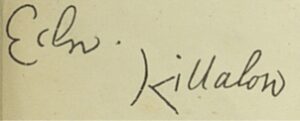

But though it would be tempting to regard this as Worth’s signature, by rare chance an authentic copy of this exists elsewhere. For despite his somewhat suspect position under the commonwealth, Edward Worth was installed Bishop of Killaloe after the restoration of Charles II in 1660. Two centuries later, when writing his history of that diocese, the Reverend Philip Dwyer, took copies of those signatures of the bishops of the diocese that could be located, and he found one for Worth at the end of his will. The original, like so much else of historical importance, was destroyed when the Public Records Office was blown up in 1922. But the facsimile is given in Dwyer’s publication, and it will be apparent that there is no similarity between the two:

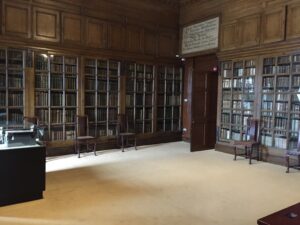

Bishop Edward Worth died at Hackney in London on 2nd August 1669 and was buried in St Mildred’s Church there four days later. Dwyer also reproduces the text of his will, which urged his wife Susanna “to consider whence she is fallen and to do her first works”. A relative of the Boyles, she had become a Quaker in 1656, which cannot have improved marital relations, and, far worse, was arrested for attending a Quaker meeting in Dublin in 1664. More pertinently, perhaps, the will divides Worth’s books between his two surviving sons, William (1646-1721); and John (c1648-1688), who became Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. In turn, John’s son, another Edward, bequeathed his library, principally of medical books, to the newly built Steevens’s Hospital in Dublin, with the proviso that it remain there in a specially furnished room. The stipulation has been complied with for almost three centuries, and today the Edward Worth Library remains more-or-less as its owner left it, and is considered to be the best collection of early modern book bindings in Ireland.

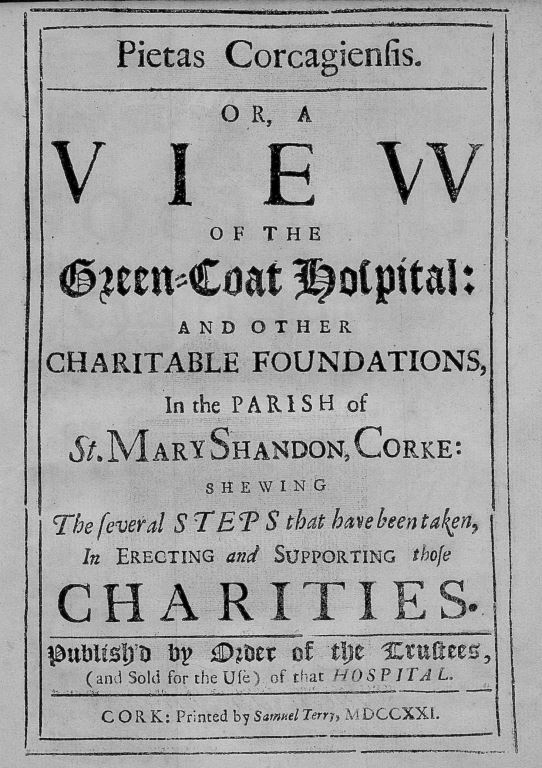

If Bishop Worth’s own books seem to have left the city where he spent most of his career, his philanthropic legacy nevertheless endured for some time. Some accounts credit him with the foundation of St Stephen’s Hospital in the South Liberties of Cork, but it would seem that it was his elder son, William Worth, Recorder of Cork in 1678, who agreed with the Corporation of the city to transfer title of the lands on which the Hospital was built in 1699. This came to be informally known as the ‘Blue Coat School’, after the colour of the uniform. Some fifteen years later, another Protestant cleric, the Rev Henry Maule (later Bishop of Cloyne) founded a charity school for children on the other side of the city, and located adjacent to St Ann’s, Shandon. Modelled on St Stephen’s, it inevitably became known as the ‘Green Coat’ Hospital. Maule published an account of the origins of the charity in 1721, entitled Pietas Corcagiensis: or, A view of the Green-coat Hospital and other charitable foundations in the parish of St. Mary Shandon, Corke, printed locally by Samuel Terry. Amongst other things, it also lists the contents of the school library at that date, and today some 282 items from the collection reside in Special Collections, a small relic from the both the book-collecting and philanthropic traditions of Cork.

Sources

Brady, William Maziere. Clerical and Parochial Records of Cork, Cloyne, and Ross. 3 vols. Dublin: Alexander Thom for the author, 1863.

Caulfield, Richard. Annals of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, Cork … Cork: Purcell & Co, 1871.

Conlon, Michael V. “Some Old Cork Charities” JCHAS 48 (1943): 86-94.

Cork City and County Archives. St Stephen’s Hospital (Blue Coat Hospital). IE CCCA/SM53.

Cotton, Henry. Fasti Ecclesiae Hibernicae: The Succession of the Prelates and Members of the Cathedral Bodies in Ireland. Volume I: The Province of Munster. Dublin: Hodges and Smith, 1851.

Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Dix, E.R. McClintock. “A List of the 17th and 18th Century Cork-printed Books [Part 1].” JCHAS 6 (1900): 168-174.

_________________. “List of all Pamphlets, Books, &c, Printed in Cork During the Seventeenth Century.” PRIA 30 (1912): 71-82.

Dwyer, Philip. The Diocese of Killaloe from the Reformation to the Close of the Eighteenth Century. Dublin: Hodges, Foster and Figgis, 1878.

Gillespie, Raymond and Andrew Hadfield, eds. The Oxford History of the Irish Book. Volume III: The Irish Book in English 1550-1800. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

Irwin, Liam. “Politics, Religion and Economy: Cork in the 17th century.” JCHAS 85 (1980): 7-25.

Lennon, Colm. “The Print Trade, 1550-1700” in Gillespie and Hadfield (2006): 61-73.

Mason, William Monck. The History and Antiquities of the Collegiate and Cathedral Church of St. Patrick, near Dublin …. Dublin: Printed for the author, 1820.

McCarthy, J.P. (Max). “In Search of Cork’s Collecting Traditions: From Kilcrea Library to the Boole Library of Today.” JCHAS 100 (1995): 29-46. Online access via CORA.

McCarthy, Muriel. “Dr Edward Worth’s Library in Dr Steevens’ Hospital.” Journal of the Irish Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons 6.4 (1977): 141-145.

Munter, Robert. A Dictionary of the Print Trade in Ireland, 1550-1775. New York: Fordham UP, 1988.