Viking Cork: A Case Study in Objects and Text

- Elaine Harrington

- July 10, 2018

The River-side welcomes this guest post on Viking Cork from Liam O’Driscoll, a student on MA in History specialising in Medieval History. Liam completed his undergraduate degree at UCC in History and Archaeology. His research focuses on medieval cartography, medieval travel texts, Viking history and archaeology.

Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, An Account of the Danes and Norwegians in Scotland, England and Ireland, 1852.

Between 1846 and 1847, an accomplished Danish archaeologist and a founder of scientific archaeology, Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, visited Ireland in search of evidence for the Viking presence here. The result of the trip was an important study of the culture of the North Sea area titled An Account of the Danes and the Norsemen in England, Scotland and Ireland. A copy of this publication printed in 1852 is now housed in Special Collections, University College Cork.

More than a century and a half later Viking artefacts are still being found by the archaeologists in Ireland. An artefact discovered in September 2017 on the site of the Cork Crawford Beamish Brewery and described by The Irish Times as a ‘1000-year-old Viking sword’ is a tangible witness to the presence of the Vikings in Cork. This item was originally used in looming or weaving activities that were essential for the Viking settlers in the production of cloths, sacks or sails for their boats.

Vikings in Ireland

The Vikings originated in the regions of Norway, Sweden and Denmark. The term ‘Viking’ possibly derives from the Vik territory that lies by the channels of Kattegat and Skagerrak running from the North Sea into the Baltic Sea. The term ‘Viking’ can also come from the Old Norse word ‘vik’ meaning ‘creek’, or ‘wic’ meaning in Old English ‘a camp’ or ‘a dwelling place’.

Numerous factors explain the movement of the Vikings out of Scandinavia. The major reasons include population growth, a demand for land, civil strife which involved the consolidation of royal power and the loss of traditional rights, and economic issues, with the latter related to silver influx into Scandinavia. As the influx of silver from the Middle East and the western Russian territories decreased, the Viking raiding increased into the west. The ability to construct ships that could navigate both open sea and rivers meant that the Vikings had the means to raid and conquer many areas and peoples.

This silver terminal of a ring brooch, dated to c. 950 illustrates the use and appreciation of silver among the Vikings. It highlights the fact that the Vikings were not merely ‘savages’.

The first reference to an assault on Cork ‘by the foreigners’, which was a term used to describe the Vikings, comes from the 820 entry in the Irish Annals of the Four Masters. The attraction for the raiders was possibly the monastery of St Finbarr that had been founded some two hundred years earlier. In 838 the Vikings burned Cork, as reported by the same Annals. Soon after a Viking settlement was established, it was attacked in 846 by the king of Munster, Olchobhar.

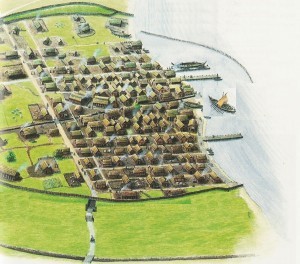

In Ireland and Britain, the Vikings established temporary settlements, with some later becoming permanent. The above illustration depicts a possible layout of the Viking settlement on the site of Cork’s South Main Street around the year 1000. The importance of the sites selected by the Vikings was reiterated by the Welsh writer, Giraldus Cambrensis (c. 1146 – c. 1223), who stated that the Norse had settled and based themselves in Ireland’s best harbours. These settlements would have smithies, weavers, butchers, and several other trades. They were often cramped places, as was the case in Cork, where the settlement was built on marshland and therefore land was limited.

This replica of the Clonmancoise crozier from the Metropolitan Museum, with the original housed in the National Museum of Ireland, is a rather beautiful example of the crossover between Irish and Viking artistic traditions known as the Hiberno-Norse style. The object illustrates the Irish adaptation of foreign cultural influences. It is inspired by the Viking Urnes art style.

Viking artefacts in the Cork Public Museum

Among the Viking artefacts discovered in Cork and now housed in the Cork Public Museum are many objects that illustrate the daily life and activities of the Vikings. Objects discussed below have been selected for the purpose of this blog with the help of the Head Curator, Daniel Breen. The artefacts represent medieval material culture from the ninth to the twelfth centuries, and reflect a wide range of economic and social aspects present in Viking Cork during that time. They are fundamental to our understanding of people’s day-to-day activities during this period. For anyone interested in the wider Viking influence in Ireland, the Waterford Treasures Museum, arguably the best museum in Ireland for Viking material, offers a wonderful wealth of comparative information.

Economy

This small item, while perhaps unimpressive at first glance, sheds light on the Viking economy and religion. It was the Vikings who introduced a currency and minting to Ireland. This type of coin dated to around 1170 and executed in a Hiberno-Scandinavian style is known as a ‘braceate’. The coin displays a cross which suggests the presence of Christian beliefs among the Irish Vikings, who converted to Christianity c. 1000. There is also a personal aspect to this object: it was placed in a pouch and handled regularly.

The Cork coin displays one variant of Viking coins found in Ireland. Viking coins are discussed by Worsaae in his Account of the Danes and Norwegians, as he writes: ‘they are of silver, and undoubtedly coined in various towns of Ireland besides Dublin, as in Limerick, Cork, Waterford and several other towns where the Ostmen had settled’.

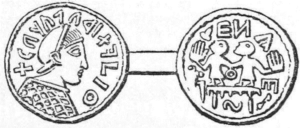

The above illustration represents an eighth- or ninth-century coin found in the Dublin area. The inscription reads ‘Canute in Dublin’ and possibly displays a profile of one Canute, who died in a siege of Dublin and was most probably the son of Gonno, a king of Denmark. The letters present a mix of Latin and Futhark-runic alphabets. This coin, possibly imported, is a particularly early indication of the use of coinage in Ireland.

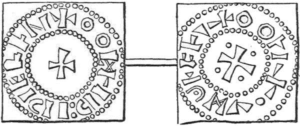

This drawing represents a coin from around the tenth century with two inscriptions that read: ‘Olaf in Dublin’ and ‘Olaf made me’. A portrait of the ruler is absent here and the coin displays religious imagery that reflects the importance of Christianity in the Viking society at this time. It is difficult to discern to which Olaf the inscription refers. Olaf Tryggvason, although not a king of Dublin, was the king of Norway around the year 1000. The coin is perhaps a mint celebrating him and his attempts at conversion of the Norse to Christianity. The second inscription suggests that the minter had the same name as the Viking ruler.

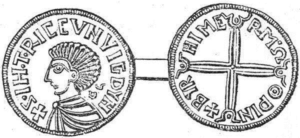

Another image of a coin reproduced by Worsaae bears the inscription ‘Sigtryg king of Dublin’. It displays a profile of a leader, most likely Sigtryg II Silkbeard Olafsson, who reigned in Dublin between 995 and 1036. The name on the reverse can be that of the minter. Sigtryg’s reign coincided with the Vikings’ conversion to Christianity and the Christian religion is expressed by the image of the cross on the coin.

The coins are important in providing an approximate date for the introduction of a monetary economy into Ireland. Varieties in coin dates and designs also illustrate trade links between the Irish Vikings and other regions, and their interest in silver and bullion.

The Cork coin fits into the period of the Viking conversion to Christianity reflected in material culture. To read more about the Viking and Hiberno-Norse coinage see this article on the BBC History website.

Clothing

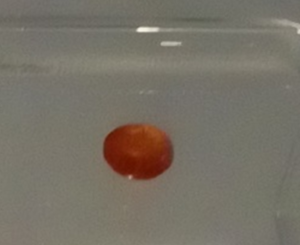

This amber bead dating to c. 1100-1150 originally belonged to a larger chain of beads such as a bracelet or necklace. Amber was imported by the Vikings from the Baltic region, and this small object illustrates a wide ranging Viking or Hiberno-Norse trade and culture.

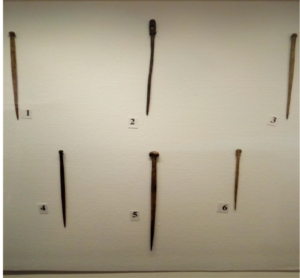

The above image displays stick pins that date from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, and ringed pins dating from c. 600 onwards into the Viking period. The ringed pin shape was used by the Vikings, and examples of such items are found across the North Atlantic in the context of Viking settlements. The stick and ring pins were used as hair ornaments and in fastening items of clothing. The Cork pins show varied designs: Object 1 is club headed stick pin with vertical lines and decorative dots, Object 2 is a baluster-headed ringed-pin with radial patterns on the ring, Object 3 has horizontal designs on the head, Object 4 has a club head and the shaft with an incised ‘x’ pattern, Object 5 is a ringed pin with lozenge shaped motifs on its upper shank, while Object 6 has a spatula head.

See here for more examples of beautiful details of Hiberno-Norse pins.

Conclusion

The Vikings left an important legacy in Ireland: they contributed to the urbanisation process, introduced Scandinavian place names and personal names, established a monetary economy and minting, and affected Irish politics for a period of approximately 400 years, between 800 and 1200. The Viking artefacts found in Cork are but a chip in the large block that is Viking archaeology. These everyday pieces illustrate the Viking economy and fashion and display a real human and practical aspect of the Viking society which is usually portrayed as violent.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Elaine Harrington and UCC Library‘s Special Collections for hosting this blog post as part of The River-side blog. I am grateful to Daniel Breen for overseeing my work placement Cork Public Museum and allowing to use the Museum’s Viking material in this blog. My thanks also go to Dr Małgorzata Krasnodębska-D’Aughton for supervising the process of creating the blog, and to Drs Damian Bracken, Diarmuid Scully and John Ware for their comments on the various stages of the blog.

Further reading

Bartlett, T., Ireland: A History, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010.

Birkett, T. and Lee, C. (eds.), The Vikings in Munster, Nottingham: Centre for the Study of the Viking Age, University of Nottingham, 2014.

Blackburn, M.A.S, Viking Coinage and Currency in the British Isles, Spink, London, 2011.

Fitzhugh, W., Ward, E.I., Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga, Smithsonian Institution Press in association with the National Museum of Natural History, London, 2000.

Hall, R., Exploring the World of the Vikings, Thames and Hudson, London, 2016.

Henry, D., ed., Viking Ireland: Jens Worsaae’s Accounts of His Visit to Ireland, 1846-47, with afterword by R. Ó Floinn, Balgavies, Angus, Pinkfoot Press, 1995.

Jefferies, H.A., “Viking Cork”, History Ireland, Vol. 18, No. 6, 2010, pp. 16-19.

Lawton, B., “Heathens, pagans, Danes… Vikings?” Medieval Manuscripts Blog – British Library. January 2019.

Roche, B., “Cork Viking Site Predates Waterford”, The Irish Times, January 2018.