The Book of Kells: Image and Text / The Chi Rho Page

- Elaine Harrington

- June 1, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

The Chi Rho Page

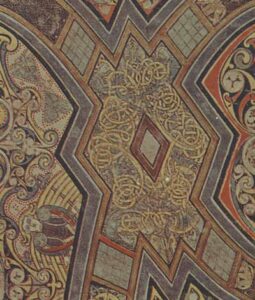

The Chi Rho page in the Book of Kells is perhaps the most elaborate and enigmatic illumination in the manuscript. The page is rich in multi-layered symbolism intended to engage its monastic audience with a range of Eucharistic and Christological themes.

A Chi Rho is formed by overlapping the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ: chi (X) and rho (P). The Kells initial also contains the third letter of Christ’s name, iota (I). When compared to other Insular manuscripts that similarly embellish the Chi Rho initials, the Kells page puts a distinct emphasis on Christ’s name with the chi alone nearly filling up the entire page. At the bottom of the page the text continues and contains the words autem generatio. The entire page celebrates the mystery of the Incarnation as it opens the Nativity story described in the Gospel of Matthew: Christi autem generatio sic erat (‘Now the generation of Christ was in this wise’, Matthew 1:18).

The verse is lavishly decorated, as if it were beginning a separate Gospel. In patristic tradition, the Incarnation was seen as an integral part of salvation that was fulfilled in the Crucifixion: Christ had to become incarnate to die on the Cross for the sins of humanity. The Kells miniature makes a visual connection between Christ’s birth and death by employing the magnificent X cross and smaller cross shapes.

Hidden within the intricate decoration are insects and animals. At the top of the page two moths feature within a spandrel of the letter chi. According to the early Church Fathers, moths symbolise the Resurrection due to their natural metamorphosis.

At the bottom of the page a pair of cats pin down the tails of two mice that nibble at the Eucharistic host, while two other mice sit on the cats’ backs. Different suggestions have been made to explain these animals’ presence, ranging from mundane to theological. The scene may depict an actual nuisance caused by mice in the monastery. The image may allude to unworthy receivers of the host, represented by the mice, and the punishment that awaits them, presented by the preying cats. On the other hand, the cats can signify the devil lying in wait for human sinners (the mice) who are saved by the Eucharist. To the right of this image there is a small black otter with a fish in its mouth, which corresponds to stories about Irish monks being supplied with fish by otters. The Life of St Kevin recounts how his monks were fed with salmon provided by an otter, while the Navigatio Sancti Brendani (The Voyage of St Brendan) tells of a hermit sustained by fish and firewood brought to him by an otter.

The animals on the Chi Rho page, according to Suzanne Lewis, can be understood as representing three parts of creation: earth (cats and mice), sea (otter) and sky (moths). Placed around Christ’s initials these animals underline Christ’s role as creator. The lozenge shape displayed in the centre of the monogram is connected to the quaternities, discussed in an earlier blog post on the four Evangelist symbols. The quadrangular world created by Christ the Logos is expressed through this lozenge shape and alludes to the fourfold nature of the Gospels, brought to the four corners of the world. As argued by Jennifer O’Reilly, ‘the underlying unity of this quadripartite world was seen to flow from its divine Creator made known in Christ’. The inclusion of the lozenge in the centre of the chi (X) shape demonstrates this link between Christ as creator and his creation. The lozenge motif recurs in the Book of Kells and is represented on the Virgin and Child miniature on Mary’s right shoulder with the Christ Child pointing at it.

The design also conceals three angels, while the curving upper terminal of the rho ends in a human head with tousled yellow hair. If you would like to know more about the symbolism behind this, read Michelle Brown’s paper on ‘Bearded Sages and Beautiful Boys’.

Natasha Dukelow

Further reading

‘Bethada Náem nÉrenn, Life of Coemgen (1)’, CELT Corpus of Electronic Texts, <http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T201000G/text007.html>.

Brown, Michelle, ‘Bearded Sages and Beautiful Boys’, in Elizabeth Mullins and Diarmuid Scully, ed., Listen, O Isles, Unto Me: Studies in Medieval Word and Image in Honour of Jennifer O’Reilly (Cork: Cork University Press, 2011), pp. 278-291.

Henry, Françoise, The Book of Kells: Reproductions from the Manuscript in Trinity College Dublin (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974).

Lewis, Suzanne, ‘Sacred Calligraphy: The Chi Rho Page in the Book of Kells’, Traditio 36 (1980), pp. 139-159.

Mussetter, Sally ‘An Animal Miniature on the Monogram Page of the Book of Kells’, Mediaevalia 3 (1977), pp. 119-20.

O’Reilly, Jennifer, ‘Patristic and Insular Traditions of the Evangelists: Exegesis and Iconography’, in Anna Maria Luiselli Fadda and Éamonn Ó Carragáin, ed., Le Isole Britanniche e Roma in Etá Romanobarbarica (Rome: Herder, 1998), pp. 49-94.

Simms, George Otto, Leaves from the Book of Kells (Dublin: A.P.C.K., 1962).

Sullivan, Edward, The Book of Kells (London and New York: The Studio, 1914).