The Book of Kells: Image and Text / Making Manuscripts

- Elaine Harrington

- May 29, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

Making Manuscripts

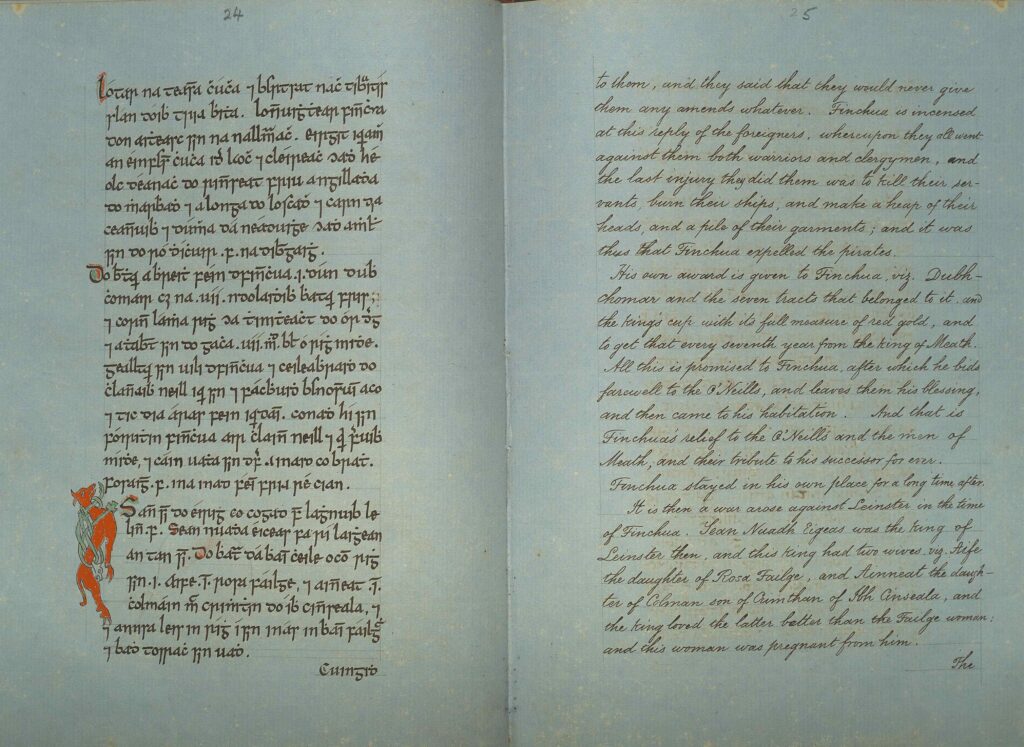

Medieval manuscripts were written by hand, the word ‘manuscript’ being derived from the Latin words ‘manu’ meaning ‘by hand’ and ‘scriptus’ meaning ‘written’. They were copied on parchment made from the skins of sheep and goats, or vellum made from calfskin. The animal skin was soaked in a lime solution and cleaned through a series of shavings, while pulled taut on a rack. It was then cut into sheets called folios (from the Latin word for a leaf) and readied for writing. The front of a folio is known as recto and the back as verso (abbreviated to r and v). Skin from a single calf produced on average three sheets.

Ink was produced by mixing various materials. The type of ink primarily used for simple lettering was made from gall and gum, darkened by lampblack. Decorated initials and full page illustrations employed a variety of pigments derived from both local and imported minerals, metals and organic materials. Some manuscripts used lapis lazuli, a stone mined in the East, to create bright blues, while indigo produced a darker blue. Gypsum was commonly used to create white, and red-lead gave red. Because of the extreme amount of time, effort and expense involved in the production of any volume, illuminated manuscripts were regarded as having special status. Researchers today can determine the type of pigments using Raman spectroscopy, a process that involves firing a laser into a single precise point and measuring how the laser light is affected. Different materials cause a different change to the wavelength of the laser.

Despite its laborious nature, the art of manuscript making has continued beyond the Middle Ages. At times, the craft has adapted to new materials, as is the case with the nineteenth-century manuscripts compiled in Ireland and housed in the Special Collections of UCC’s Boole Library. These manuscripts were written in the Irish language on paper instead of vellum.

Another more recent example of the Irish manuscript is The Great Book of Ireland, created between 1989 and 1991 and also housed in the Boole Library. The folios of this volume are made of vellum following medieval tradition and display a compilation of contemporary Irish art and poetry.

Connor White

Further reading

Alexander, Jonathan J.G., Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

De Hamel, Christopher, A History of Illuminated Manuscripts (London: Phaidon Press, 1997).

Kelly, Henry Ansgar, ed., Medieval Manuscripts, Their Makers and Users: A Special Issue of Viator in Honor of Richard and Mary Rouse (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011).