From 18th century Tipperary to 20th century Cork: Insights into Handwritten Records in a Private Residence and an Academic Institution

- Elaine Harrington

- September 21, 2021

The Riverside welcomes this guest post from Úna Faller who in summer 2021 undertook an online work placement in Special Collections using digital surrogates of The Donations Book 1931-1955 and Library Book of Barne House (1774). Úna completed her undergraduate studies in English and French in University College Cork in 2021. In final year, she focused on representations of gender and women, as well as the environment in Anglo- and francophone literature. She is currently studying for a Master in Rare Books and Digital Humanities in the Université de Franche-Comté, Besançon, France. Her research interests include the future-based environmental demands of material conservation and preservation, as well as the future form of libraries and access to materials.

Handwriting over the Centuries

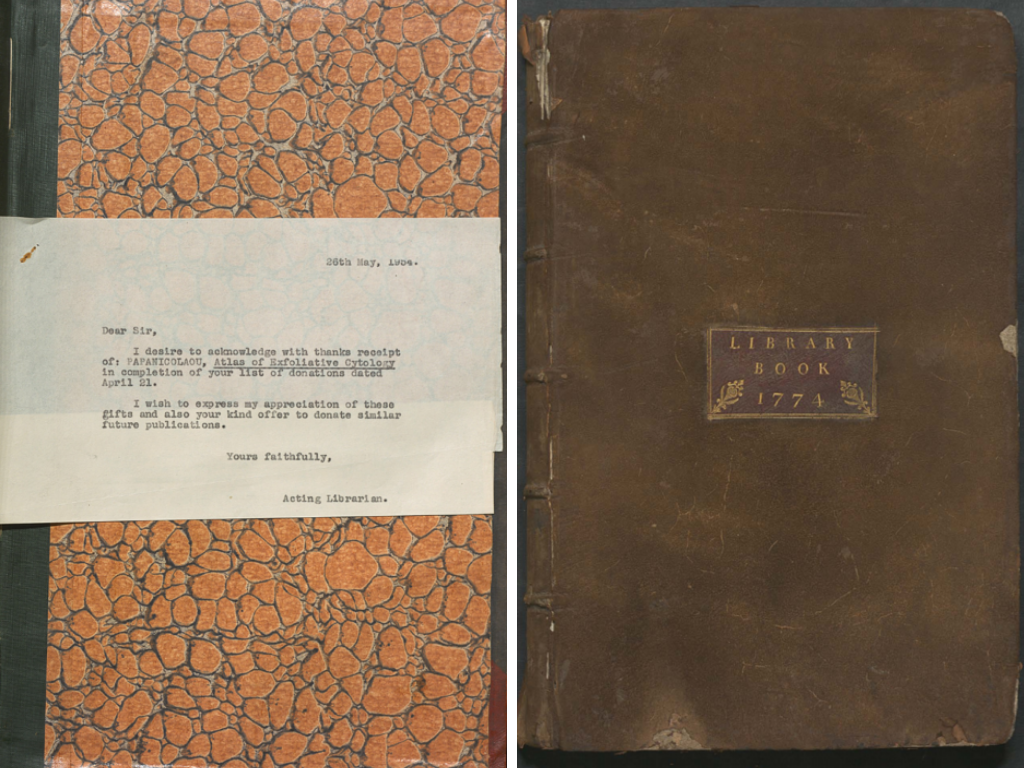

Modernity has changed the way we read and absorb information. We spend so much time engaging with the neat and uniform characters of typed print that the handwriting of previous epochs requires much focus and patience to decipher, at least to the lay transcriber. The disorientating loss of immediate comprehension that accompanies the hand-written texts of alien scribes of former centuries, does however reward the reader with intriguing insights into the past. Two items from UCC Library‘s Special Collections, namely the Donations Book 1931-1955 and the Library Book of Barne House (1774), offer these tangible glimpses into their respective timeframes.

Right: The front cover to the Library Book of Barne House, U.388, Special Collections, UCC Library.

Receiving and Recording Donations

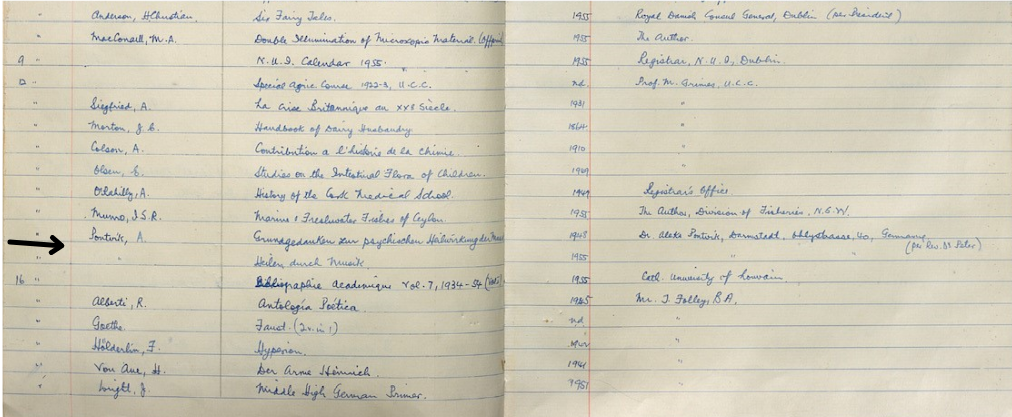

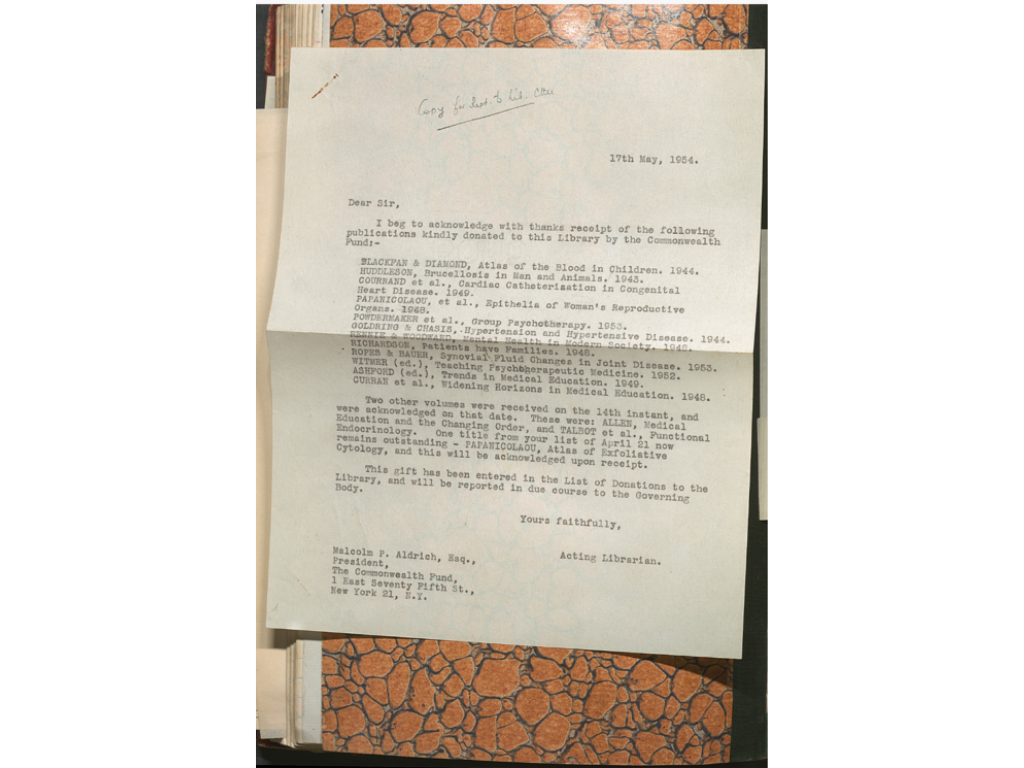

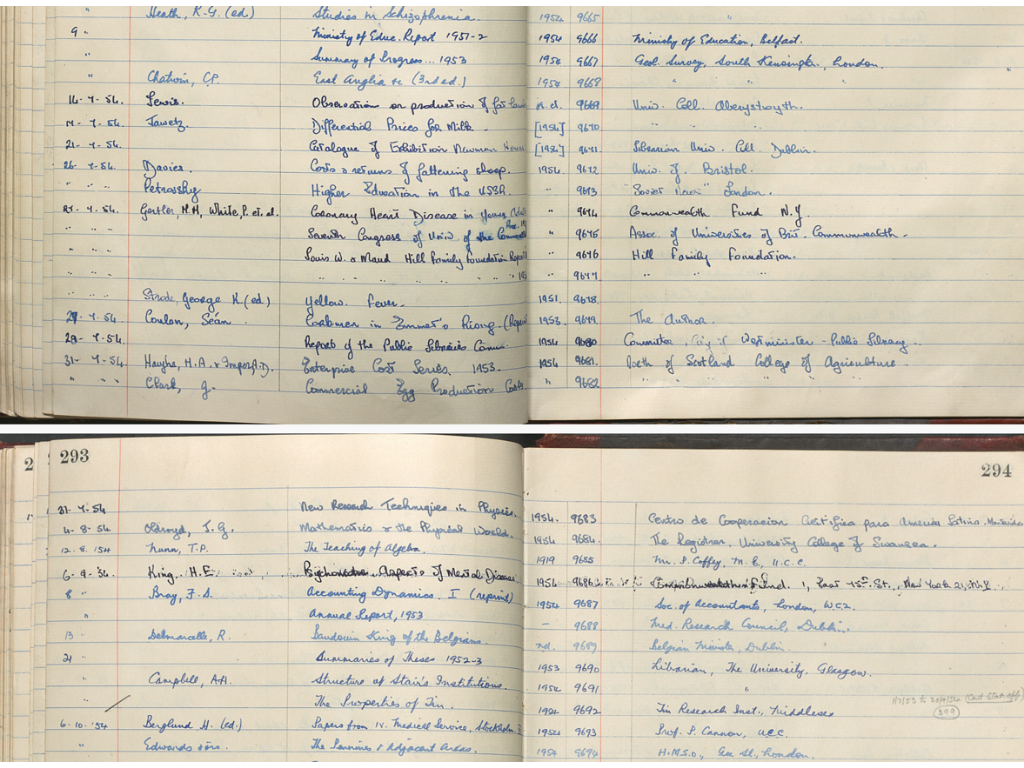

The Donations Book 1931-1955 is a hand-written catalogue of all items UCC’s Library received via donation in this time period. The donors vary, from private individuals from the Greater Cork area and lecturers attached to the university, to public institutions and international societies. The section pertaining to the years 1953-55 contains over 600 items with widely differing subject matter, such as science, local geography, committee reports, and examination papers.

Two Scribes

The handwriting for the majority of entries becomes comfortingly familiar after the initial labour of character recognition. The section from 1953-55 contains 2 different hands and a short interlude completed with the use of a typewriter. ‘Scribe A’, who opens this section, uses a tidy letter formation and a consistent font size. This scribe makes up the majority of the entries, making the 1953-55 section largely straightforward to transcribe to a version that is readable online.

‘Scribe B’ appears halfway through page 291, an alluring opportunity to project a modern imagination onto the occurrences of the past. The items on this page and continuing to page 293 were donated over the June-August period in 1954, which allows the modern reader to wonder whether ‘Scribe A’ was on summer leave. Indeed, ‘Scribe B’ disappears after an entry on the 6th of September 1954, leaving behind an indecipherable donor listing and facilitating the return of the familiarity of ‘Scribe A’.

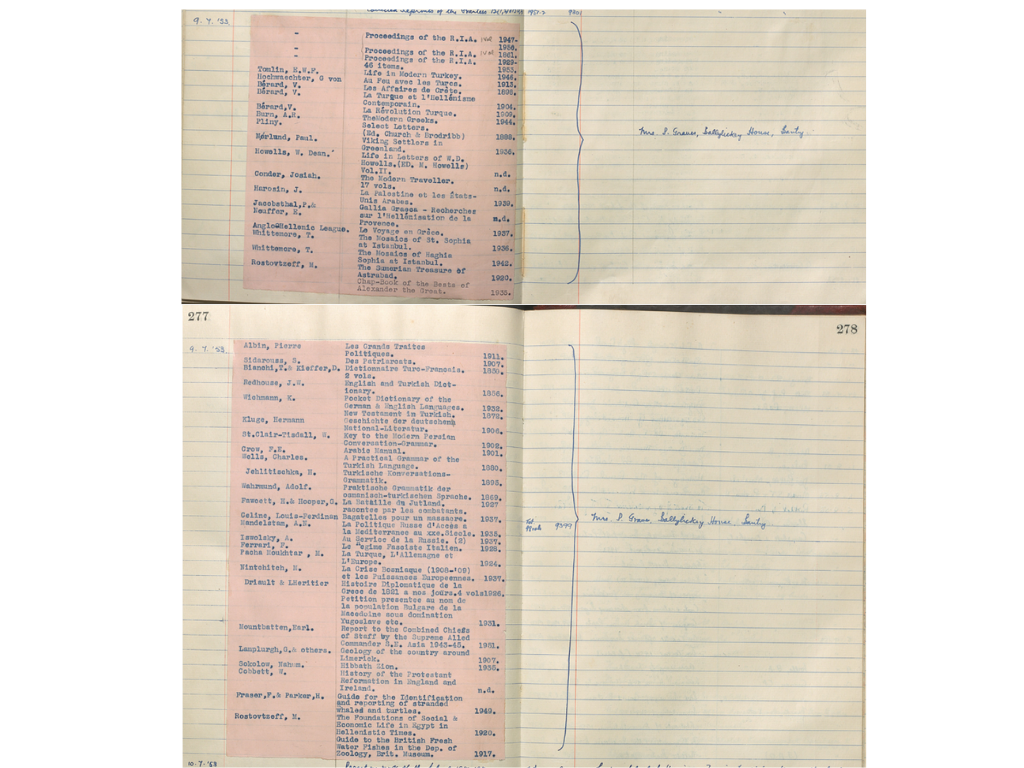

Ballylickey House Library

Transcribing from the pink pages of the typewriter, which starts halfway on page 275 and continues for most of page 277, provides a brief relief from the task of hand-writing decryption. What is most interesting about this section is the common donor. In 1953, a Mrs. P. Graves from Ballylickey House, Bantry, is recorded as donating 47 items, with texts in French appearing beside RIA material and Persian grammar manuals.

Internet research, unavailable to the scribes of this item, allows the modern user to uncover the donor’s history. According to this website, the Graves family assumed ownership of Ballylickey House sometime after 1800 and occupied it for at least four generations. Its modern status as a hotel residence intersects with this historic and dramatic dispersal of its library, allowing the modern observer to suspect that perhaps 1953 was the start of the end of the private occupation of Ballylickey House.

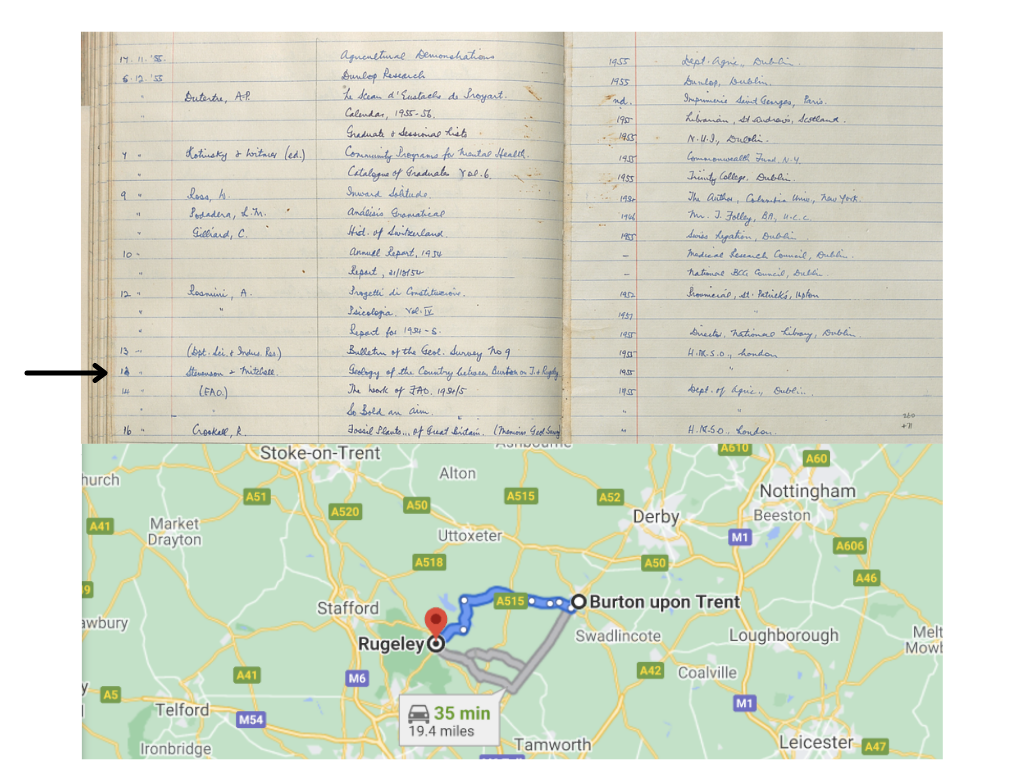

Getting Lost and Finding Direction(s)

Using the tools of the internet to successfully decipher many entries was a rewarding aspect of this project. One such tool was Google Maps. Page 309 of the item contains a reference to two towns in the United Kingdom, with the donated item exploring the geology between them. Having figured out the name of one town, I was able to use Google Maps to see nearby townlands. By recognising just some of the letters of the second town, combined with a process of elimination, I could use the digital version of the word to uncover the hand-written mystery and successfully record the entry.

Bottom: Google Maps – Distance between Rugeley and Burton upon Trent

Other resources included academic and scholarly databases, where the donated item was cited by a more modern article. For example, the bibliography of this article (listings 85 and 87) helped me to identify the two items donated by an A. Pontvik on page 307.

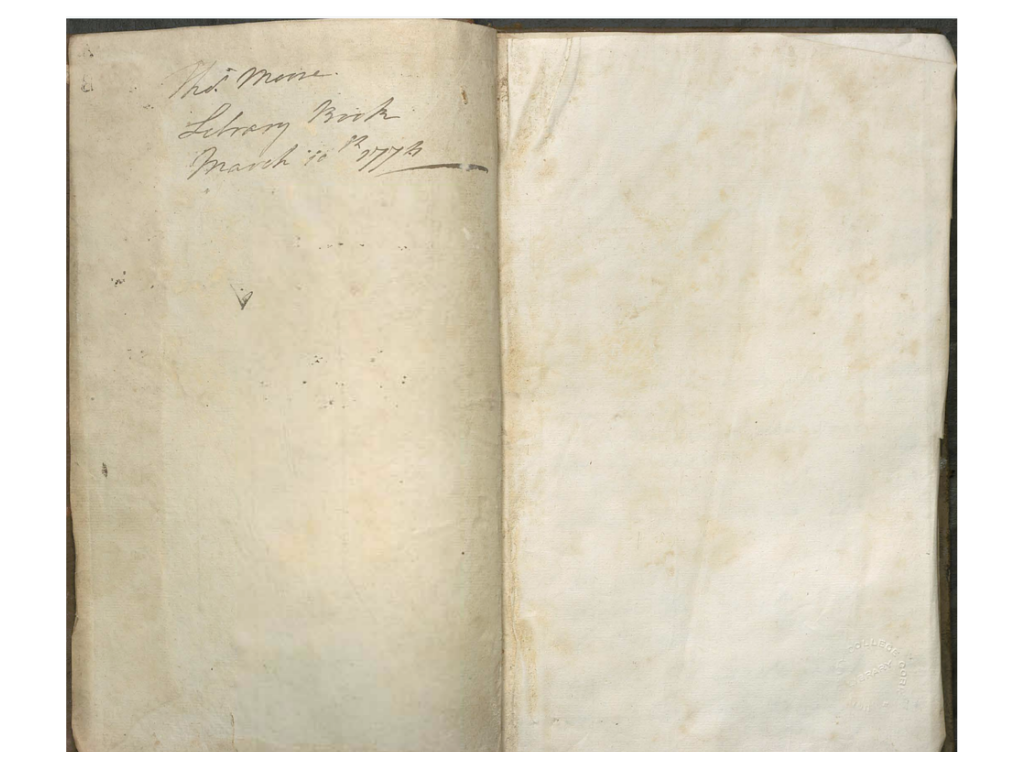

Library Book of Barne House, Tipperary

Moving backwards through the centuries to arrive at 1774 deposits the modern reader in an even more bewildering graphological setting than that of the Donations Book 1931-1955.

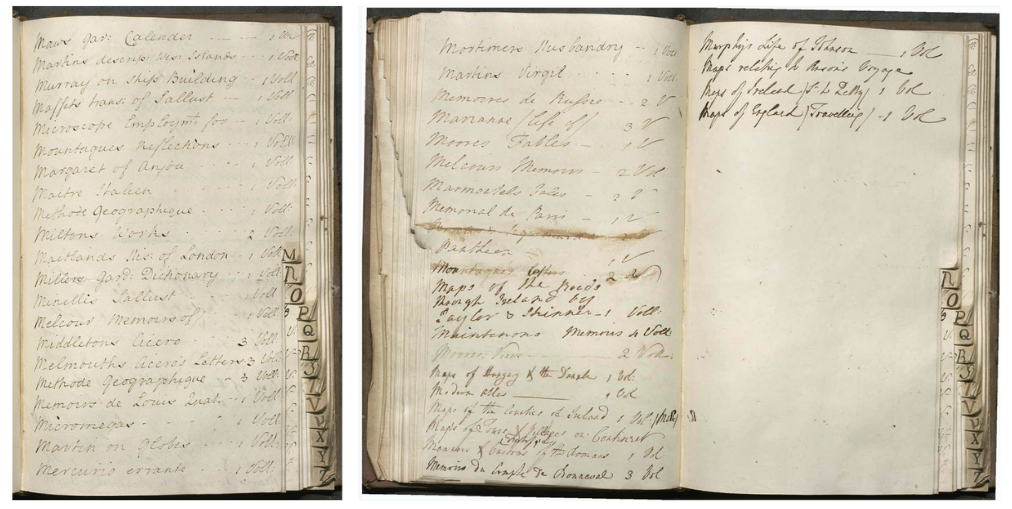

Recording the contents of Barne House, Tipperary, the Barne Library Book offers a comprehensive insight into the preoccupations of the Moore family and their literary interests. It contains an alphabetised list of texts in English, French, Italian and Latin, with items touching on the sciences, poetry, local history and geography, as well as ancient classics and maps.

The item reveals the presence of at least 2 distinct scribes, and possibly a third. One scribe was Thomas Moore, the son of Richard Moore who compiled the library’s collection. His signature can be found on the opening pages of the item, a definitive claim of ownership over the work.

17th Century Challenges for a Modern Transcriber

He opens the A listing and continues with his presence for the majority of entries. There is also the noticeable and sporadic inclusion of a second hand, who is responsible for many modern interpreting difficulties. For example, letter identification becomes increasingly difficult between the M recto, the M verso and the M(2) recto pages. This difficulty is largely attributable to the presence of this second scribe.

Technology was also crucial in digitally recording this item’s contents. Many of the items from the Barne House library were auctioned over the years, with their lot numbers available online. Cross-referencing these online entries from auctioneers such as Fonsie Mealy’s and via online booksellers such as biblio.com was helpful in distinguishing unfamiliar letter patterns and ultimately deciding on the spelling for entries that were unclear.

Special Collection Items and Their Inherent Liminality

The liminality of this kind of item is striking to consider in tandem to these handwriting intrigues. Its existence points to a different society, one that is unlikely to arise again, where a gentleman of a Big House collects such a wide variety of texts and records them in a hand-written document. The inherence grandiosity of this gesture belongs to its time period, and the preservation of this item by Special Collections is indicative of its liminality. While the items may be dispersed and no longer in their original setting, the existence of this catalogue binds them to 1774, eternally serving as a historical reminder of this epoch.

Public vs Private Access to Information

A separate issue to hand-writing discourse that arises from considering the Donations Book 1931-1955 and the Barne Library Book is the divide between private and public access to knowledge. Contained in their own spatial and temporal setting, treating the items in conjunction with one other creates a discourse on the dissemination of knowledge.

The numerous donations recorded by the UCC Boole Library in the Donations Book 1931-1955 represents the movement of knowledge and information from private hands to an institution that provides access to learners and students. The items received via donation have a far greater reach than those recorded in the Barne Library Book, whose existence is testimonial to the inequalities inherent in the ability of the wealthy to amass huge collections of knowledge that remain privatised. While this particular collection was facilitated by the societal realities of the late 18th century, inequalities in knowledge access systems still remain.

It is also finally fascinating to reflect on the inverse nature of both items. The Donations Book 1931-1955 represents items that were decidedly unconnected to one another, and which are now contained in a singular collection, while the items of the Barne Library Book were attentively curated by one family but exist now as mere dispersed parts.