The Luttrell Psalter: Knighthood, Hospitality and Piety / The Office of the Dead

- Elaine Harrington

- January 18, 2019

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

The Luttrell Psalter and the Office of the Dead

Themes of power and nobility present throughout the Luttrell Psalter are combined with the theme of piety and an ideal of a good Christian life. Sir Geoffrey Luttrell commissioned the Psalter to celebrate his life achievements and chivalric virtues, while simultaneously providing the means of praying for him and his family after their deaths.

These prayers offered for the deceased petition God for their souls’ salvation and constituted what was called the Office of the Dead. The typical Office included selected texts of Psalms along with other Old Testament readings that describe God’s mercy for a sinner. In the Luttrell Psalter the Office of the Dead that starts on folio 296r, follows the Litany of the Saints, who were evoked for the protection of both the living and the dead. The entire book celebrates not only the Luttrell family’s sense of pride and religious devotion but also expresses their concern with the afterlife and the fear of Purgatory.

The doctrine of Purgatory attested that after physical death souls may undergo purification to satisfy God’s justice until their sins were fully atoned for. Sins could be absolved through confession saving the soul from eternal damnation, but the temporal effect of sin had to be compensated by the acts of penitence, devotion and charity.

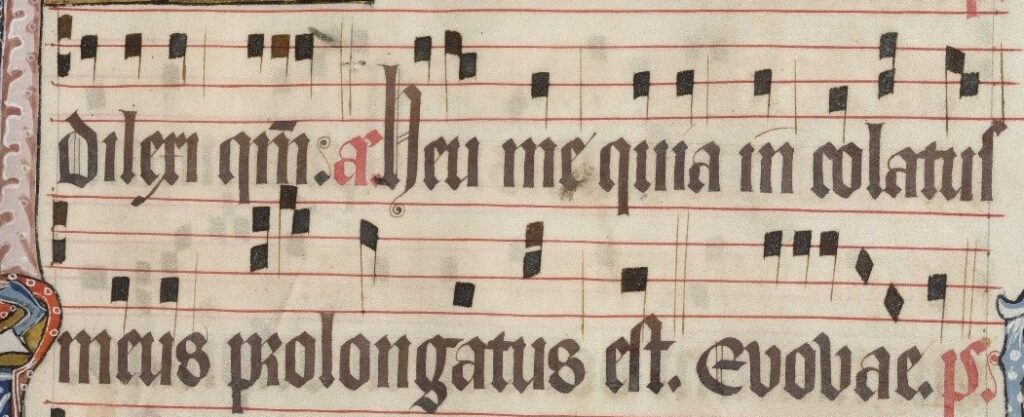

A contorted figure beneath the initial ‘P’ may represent a tormented soul awaiting relief from Purgatory and echoing the nearby text Heu me quia incolatus meus prolongatus est / ‘Woe is me, that my sojourning is prolonged!’ (Psalm 119:5). A person could never be certain of having performed enough penance during their lifetime. Thus, family and friends could help shorten their time in Purgatory, through prayers, Mass and the Office of the Dead.

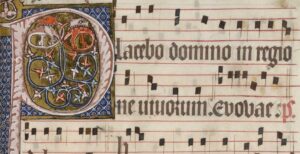

The image of the stag on the same folio may in turn represent the soul nourished by the fountain of the living God as described in Psalm 41, that is copied on folio 81r of the Luttrell Psalter.

The Office of the Dead at the end of the Luttrell Psalter emphasises the importance placed on praying for the departed in medieval society. When Geoffrey Luttrell commissioned the book, he was advancing in years and making preparations for his death, as seen in his surviving will. The Psalter was not simply a magnificent piece of artistry but ultimately an invaluable investment for its benefactor’s soul after death.

What is the Office of the Dead?

Medieval burials were a community affair. The priest was the representative of the community. He received the body of the deceased into the church, as he had received the child in baptism years before. The priest provided the funeral Mass, but the laity were encouraged to remember the dead in their own prayers and devotions, for example through the Office of the Dead.

In the Middle Ages, the daily liturgy of the Divine Office was supplemented by a series of other prayers, which were recited alongside the eight canonical hours. One of these supplementary offices was the Office of the Dead. But unlike the Divine Office, it only included three hours, namely Vespers, Matins and Lauds.

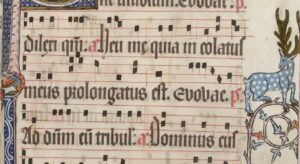

The Office has a unique order of Psalms and it opens with the antiphon for Vespers, Placebo Domino in regione vivorum / ‘I will please the Lord in the land of the living’ (Psalm 114:9) which in the Luttrell Psalter received a beautiful initial ‘P’. The letter is filled with two interlaced beasts whose tails are decorated with foliage. The entire Psalm 114 opens with the words Dilexi quoniam / ‘I have loved because’ (Psalm 114:1) as it evokes deep emotional turmoil and hope in God’s mercy, and praises God’s protection throughout a person’s life, from youth until death.

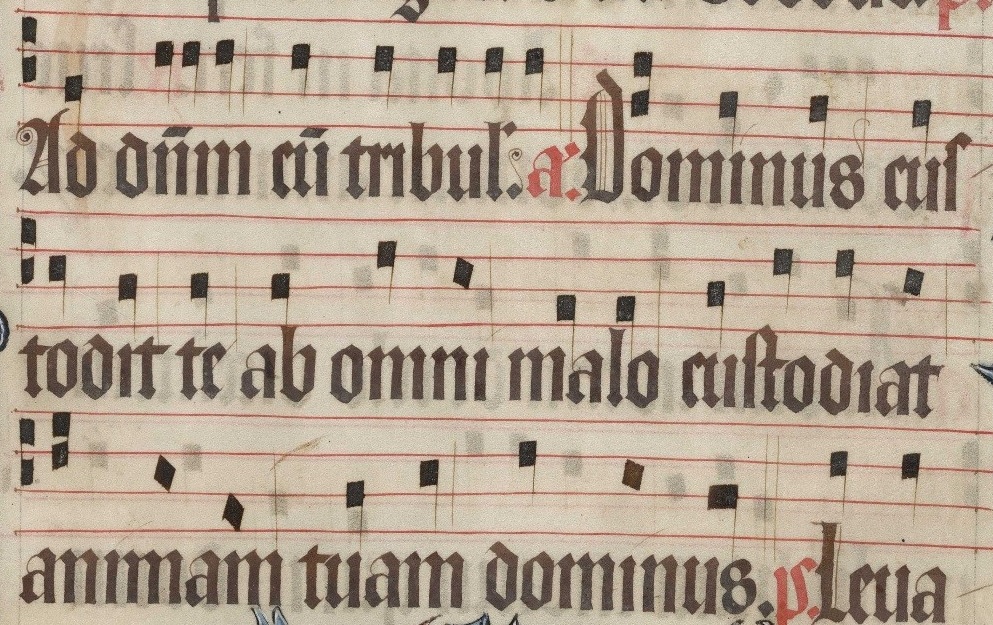

The next antiphon of the Office of the Dead seen on folio 296r is Heu me quia incolatus meus prolongatus est / ‘Woe is me, that my sojourning is prolonged!’ (Psalm 119:5). The entire Psalm opens with the words Ad Dominum cum tribularer clamavi / ‘In my trouble I cried to the Lord’’ (Psalm 119:1). Like the previous Psalm, this one features the same themes of tribulation and deliverance.

The third antiphon on the folio reads Dominus custodit te ab omni malo custodiat animam tuam Dominus / ‘The Lord keepeth thee from all evil may the Lord keep thy soul’ (Psalm 120:7). This Psalm opens with the words Levavi oculos / ‘I have lifted up my eyes’ (Psalm 120:1) and emphasises God’s protection of his chosen ones.

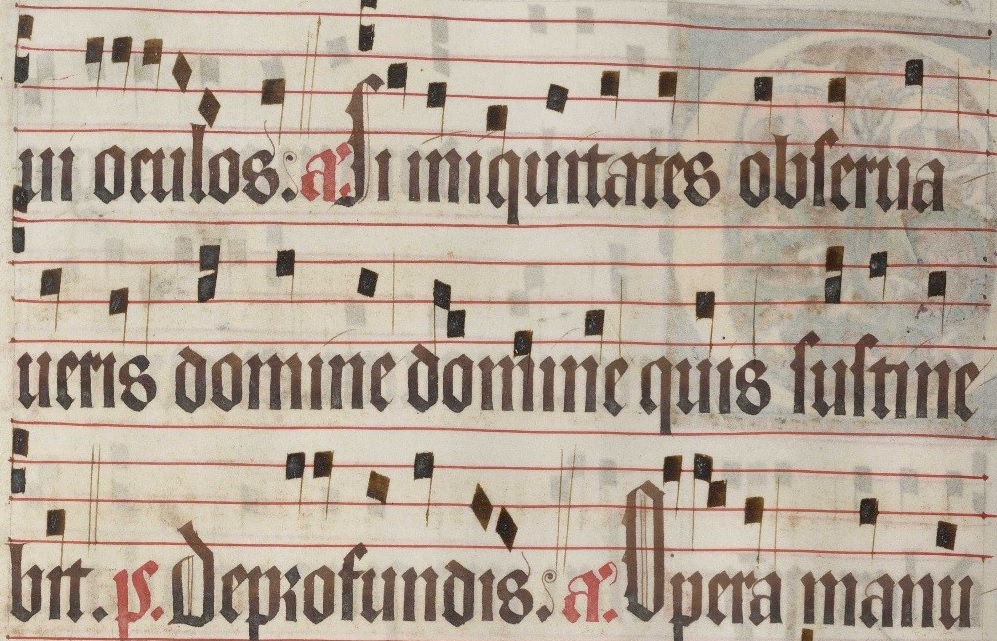

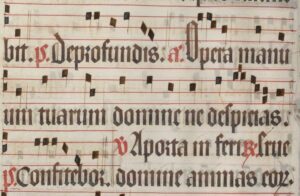

The Office of the Dead continues on folio 296v with two more antiphons. The antiphon Si iniquitates observaveris Domine, Domine, quis sustinebit? / ‘If thou, O Lord, wilt mark iniquities Lord, who shall stand it’ (Psalm 129:3) comes from the Psalm that opens with the cry of De profundis / ‘Out of the depths’ (Psalm 129:1).

The last antiphon Opera manum tuarum, Domine, ne despicias / ‘O despise not the works of thy hands’ (Psalm 137:8) comes from Psalm 137 that opens with the word Confitebor / ‘I will praise’ (Psalm 137:1).

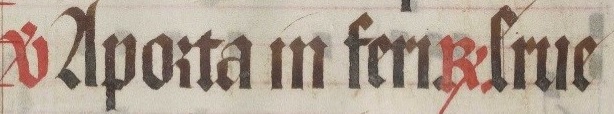

The five antiphons and Psalms of Vespers for the Dead conclude with a versicle A porta inferi / ‘From the gate of hell’ and the response Erue Domine animam ejus / ‘Deliver his soul, O Lord’.

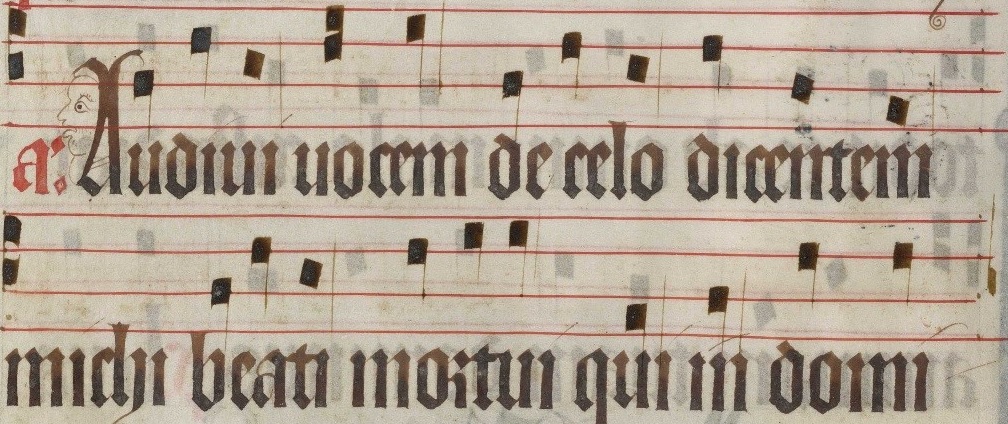

The next antiphon reads Audivi vocem de cælo, dicentem mihi: Beati mortui, qui in Domino moriuntur / ‘I heard a voice from heaven, saying unto me: Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord’. These words come the Book of Revelation (Rev 14:13).

The Magnificat canticle that follows on folio 297r is based on Mary’s words of praise and jubilation as expressed in the Gospel of Luke 1:46-55. The Magnificat is in turn followed by Kyrie Eléison and Pater Noster, and a series of versicles and responses.

Remembering the Dead

Death and remembrance were important to medieval Christians. The fate of the souls in Purgatory was dependent on the loving goodwill of others. Mass and the Office of the Dead were said during the week after one’s death and followed by the month’s anniversary; subsequently annual remembrance would take place in perpetuity. According to medieval wills and registers, people wished that their names should be kept in constant memory and in the prayers of the living after their death.

Tomás Miller

Bibliography

Dowdall, Joseph, ‘The Liturgy and Death’, The Furrow, 8, 1957, pp. 617-630.

Duffy, Eamon, Marking the Hours: English People and Their Prayers 1240-1570, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011.

Duffy, Eamon, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400-1580, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992.

Le Goff, Jacques, The Birth of Purgatory, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

MacGregor, James B., ‘Negotiating Knightly Piety: The Cult of the Warrior-Saints in the West, ca. 1070-ca. 1200’, American Society for Church History, 73/2, 2004, pp. 317-318.