The Book of Kells: Image and Text / The Temptation of Christ

- Elaine Harrington

- June 2, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

The Temptation of Christ

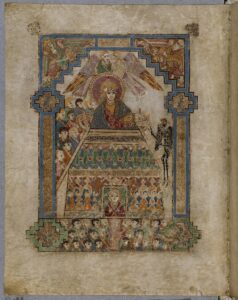

The temptations of Christ are described in the Gospels of Mathew (4:1-11), Mark (1:12-13) and Luke (4:1-13). Following forty days of fasting in the desert, Christ is tempted by the devil three times. The final temptation takes place at the Temple in Jerusalem and aims to test Christ’s divinity by asking him to throw himself from the Temple to verify whether the angels would protect him. The Kells scene described as the Temptation of Christ is set within Luke’s Gospel (folio 202v). It shows Christ on top of the box-like structure flanked by two angels above, with a black winged figure of the devil possibly holding a lasso placed to the right. The illustration contains curious features that raise a number of questions. Why is Christ’s unusually large body emerging from the Temple? Who is the small figure in the door and who are the other human figures? What is the meaning of the angels and the devil?

The most prominent figure in the Temptation miniature is the enlarged Christ placed atop the Temple. A particularly influential treatise on the significance of the Old Testament Temple was written by the Anglo-Saxon exegete Bede (c.672-735). Bede interprets the Temple as having multiple and spiritually intertwined meanings. It was God’s house built by King Solomon in Jerusalem (1 Kings 6:1-17), that as Bede says is ‘a figure of the holy universal Church’ made of the faithful, who act as the living stones with Christ as its cornerstone. As argued by Jennifer O’Reilly, the Temple in exegetical tradition was not just an earthly location but a spiritual concept beyond spatial or temporal limits. The Kells Temptation miniature visually expresses these ideas by showing Christ and the Temple becoming one.

The permanent Temple built by Solomon in Jerusalem replaced the portable Tabernacle carried by the Israelites for forty years in the desert, as the place of the meeting between God and his people (Exodus 7:16). The holiest area of the Tabernacle contained the Ark of Covenant with the tablets of the Ten Commandments and could only be attended by Aaron, the high priest and his descendants (Exodus 25–31 and 35–40). According to St Paul, the Church was the new Tabernacle ‘set up by the Lord, not by man’ with Christ becoming the new high priest (Hebrews 8:2, 4:14). Two angelic figures featured above Christ’s head may further link the Kells image to the Tabernacle. Their number and position allude to the cherubim placed on top of the Ark of the Covenant from where God’s voice was to be heard (Exodus 25:22). They may also allude to Luke 4:10-11 where the devil tempts Christ and states that the angels should come to his aid if he leaps from the Temple. The framed figure in the doorway may depict the priestly figure of Aaron in the Tabernacle, King Solomon, the builder of the Temple or Christ himself.

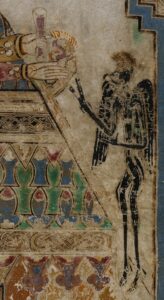

The angels and Christ are comparable to other figural representations in the Book of Kells, while the structure of the Temple recalls box-shaped Irish shrines such as the eighth-century Ranvaik’s casket. The skinny devil is however decidedly different, and his depiction can be related to some Byzantine representations. He appears to be using a lasso to ensnare Christ, who in turn is pointing a scroll at the devil. This image recalls the notion of a monastic community under attack, which is described in a treatise of the sixth-century monk, John Climacus. Later representations of John’s text show monks being lassoed from a ladder ascending to heaven. The Kells image and these Byzantine depictions represent elongated black devils holding a lasso.

Opposite, at the other side of the Temple, is a human figure holding a shield that symbolises the spiritual protection provided by the word of God as expressed by the Psalmist who says: ‘His truth shall compass thee with a shield’ (Psalm 90:5, cf. Ephesians 6:10-18).

Donncdha Carroll

Further reading

Connolly, Seán, trans., Bede on the Temple with ‘Introduction’ by Jennifer O’Reilly (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 1995).

Farr, Carol Ann, The Book of Kells: Its Function and Audience (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997).

Hourihane, Colum, ed., From Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian to the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

Meehan, Bernard, The Book of Kells, An Illustrated Introduction (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012).