The Book of Kells: Image and Text / The Carpet Page

- Elaine Harrington

- June 2, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

The Carpet Page

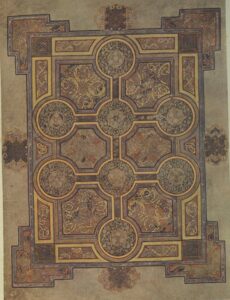

In the Book of Kells, the carpet page on folio 33r is positioned opposite the miniature of Christ enthroned, folio 32v and followed by a blank folio 33v that in turn faces the splendidly decorated Chi Rho monogram on folio 34r.

But what is a carpet page?

The name ‘carpet pages’ is given to manuscript pages that consist largely of ornamentation with complex patterns of geometrical and zoomorphic interlace decorated with vivid colours. Carpet pages usually feature in front of the Gospel text. It is worthwhile to consider their location and the very name of the pages. The name and origins of these pages possibly lie in their resemblance to rugs and prayer mats. Lawrence Nees suggests that the origin of the term ‘carpet page’ is relatively modern. The earliest mention of the term is found in a 1940 essay by Ernst Kitzinger who describes the ornamental page in the Lindisfarne Gospels as filled with ‘carpet-like-patterns’. Prayer mats were used in Christian and Muslim worship in the East, and Bede (c.672-735) also mentions the use of such mats in Northumbria. Prayer mats marked a transition space and provided a devotee with place for prayer and meditation. In manuscripts, carpet pages mark the transition from preliminary texts to the Gospels or the transition between each Gospel account, thus preparing the reader for the sacred text.

Carpet pages in Insular manuscripts often experiment with different forms of the cross. In the Book of Kells we see a carpet page containing a double-armed cross with eight circles set at the intersections and terminals of the cross shafts. A visual emphasis on the number eight in relation to the cross can be understood through sacred numerology, as expounded by Church Fathers including St Augustine (354-430). The number eight represents Resurrection and salvation as Christ rose on the eighth day of the Passion week. According to exegetes this week also known as Holy Week begins the previous Sunday, making Palm Sunday the first day and Easter Sunday the eighth day of the week. The number also alludes to baptism that was prefigured in the cleansing of the world during the Flood when eight members of Noah’s family were the only humans to survive the Flood (Genesis 7:7). The Book of Genesis 17:10-14, states that circumcision should take place on the eighth day of a male’s life to mark the covenant with God. According to Augustine, baptism is the circumcision of the heart and baptism and Resurrection become part of the salvation process.

The Book of Kells is curious in that it only contains one carpet page, though parallels are found in other Insular manuscripts such the Book of Durrow, and Lindisfarne, Durham and Lichfield Gospels. It has been suggested that each Gospel in the Book of Kells would have originally been preceded by a now lost decorated page. The motif is already fully developed in the Book of Durrow, which dates to the late seventh century and is also housed in Trinity College Dublin (MS 57). As Jonathan J.G. Alexander notes, the similarity between the two carpet pages suggests that the Durrow example may have been the model for the Kells folio.

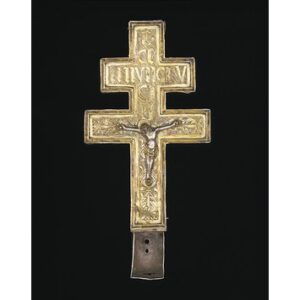

The double-armed cross is unusual in Insular carpet pages and survives only in the Book of Durrow and Kells. This form of the cross originated in eastern Mediterranean art and had a very specific meaning referring to the shape of a reliquary of the True Cross, that contained the fragments of the Cross on which Christ was crucified along with the titulus (the title board). Fragments of the True Cross were highly prized throughout Christendom. In Ireland, a relic of the True Cross was enshrined in the Cross of Cong commissioned by the High King Turloch O’Connor (1106-1156), while another famous Cross relic was housed in the Cistercian Holy Cross Abbey, Co. Tipperary.

The carpet pages of Durrow and Kells were intended to represent the True Cross and allude to Christ’s Passion. Patristic traditions linked the Incarnation and salvation with the theology of the Cross. This link is visually expressed in the position of the Kells carpet page, folio 33r in the proximity of the Chi Rho monogram on folio 34r that proclaims the birth of Christ (Christi autem generatio).

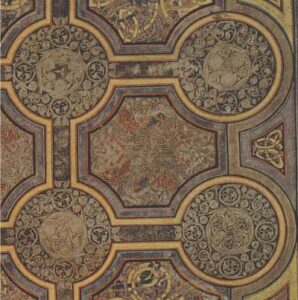

A myriad of intricate details are contained within the sections between the arms of the cross and its border. Concealed within the intricately laced patterns are minutely executed interwoven depictions of lions with protruding tongues and long manes, snakes, peacocks and human figures. The animals allude to salvation: snakes that shed their skin are linked to renewal, peacocks whose flesh does not decay represent everlasting life, while lions allude to the Resurrection but also to Christ who descended from the tribe of Judah symbolised by a lion and is described as the Lion of Judah in the Book of Revelation 5:5.

On a side note, the figure of the Lion of Judah inspired C.S. Lewis in representing Aslan the lion in the Chronicles of Narnia.

Natasha Dukelow

Further reading

Alexander, Jonathan J.G., ed., A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, vol. 1: Insular Manuscripts, 6th to the 9th Century (London: Harvey Miller, 1975).

Brown, Michelle P., The Lindisfarne Gospels and the Early Medieval World (London: British Library, 2011).

Hitchens, Megan M., ‘Building on Belief: The Use of Sacred Geometry and Number Theory in the Book of Kells, fol. 33r’, Parergon 13/ 2 (1996), pp. 121-136.

Herren, Michael W. and Shirley Ann Brown, Christ in Celtic Christianity: Britain and Ireland from the Fifth to the Tenth Century (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2002).

Livesey, Nina E., Circumcision as a Malleable Symbol (Heidelberg: Mohr Siebeck, 2010).

Nees, Lawrence, ‘Ethnic and Primitive Paradigms’, in Celia Chazelle and Felice Lifshitz, ed., Paradigms and Methods in Early Medieval Studies (New York: Springer, 2016), pp. 40-56.

O’ Reilly, Jennifer, ‘Exegesis in the Book of Kells; The Lucan Genealogy’, in Felicity O’Mahony, ed., The Book of Kells: Proceedings of a Conference at Trinity College Dublin, 6-9 September 1992 (Aldershot: Scolar Press for Trinity College Library Dublin, 1994), pp. 334-397.

Simpson, Raymond, The Lindisfarne Gospels (Stowmarket: Kevin Mayhew Ltd, 2013).

Sullivan, Edward, The Book of Kells (London and New York: The Studio, 1914).