The Book of Kells: Image and Text / The Virgin Mary

- Elaine Harrington

- June 1, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

The Virgin Mary

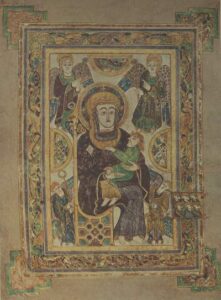

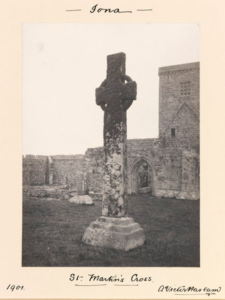

The miniature on folio 7v of the Book of Kells is the earliest surviving representation of the Virgin in a western manuscript, as noted by Martin Werner. Devotion to the Virgin Mary is well attested in Ireland and her cult developed there during the early Christian period. Peter O’Dwyer argues that the earliest reference to the Virgin in Irish writings is found in an Old Irish prophecy dated to c. 600. Mary’s cult was also well established within the Columban monastic network, as seen in her depiction on the shaft of St Martin’s Cross at Iona.

The Kells image depicts a tender moment between mother and child but the miniature’s original monastic audience would have been acutely aware that the image was not only a point of emotional connection as modern viewers may understand, but was also intended to be read in terms of the doctrines and mysteries surrounding the Incarnation of Christ.

Mary’s mantle is purple, the colour of royalty, and she wears a brooch in the shape of a lozenge with four smaller lozenges contained within it. The shape occurs on other Kells pages such as the Chi Rho page. The dominant position of the Virgin demonstrates the high respect with which she was treated, and her portrayal as enthroned celebrates her majesty. The halo around her head bears three crosses that link her to the Trinity, and suggests not only Mary’s sanctity but also her role in salvation. Mary plays an integral part in the Incarnation, through which the second person of the Trinity (Christ) becomes flesh for the redemption and salvation of humanity fulfilled through his Crucifixion. Interestingly, Christ is destitute of a halo. As this symbol indicates divinity, its presence around Mary’s head in the Kells miniature celebrates her as the Mother of God, while the lack of the halo around Christ’s head emphasises his humanity.

In the right margin of the miniature, six profile heads look across, signalling that the image and facing page should be read in conjunction. The depiction of the Virgin and Child offers an appropriate preface to folio 8r with the text of the breves causae of Matthew, which presents a summary of his Gospel, and begins with Nativitas Christi in Bethlem (‘The Birth of Christ in Bethlehem’). The angel on the lower left of the miniature holds a flabellum (a fan used to protect the Eucharist from flies) with a twelve-petal rosette. This motif is picked up on the following page, as it defines the shape of the initial letter on the facing Nativitas text, and according to Bernard Meehan, former Keeper of Manuscripts, TCD, it represents the Star of Bethlehem (Matthew 2:7-11).

The draping of Mary’s clothing in the Kells miniature clearly reveals her breasts. The triple dots on her robes follow a Near Eastern tradition of using the motif to denote garments of the highest quality. However, here the triple groupings seem to allude to the Trinity and as they are white, the dots according to Meehan represent the mother’s milk. This Irish Virgin is shown as a fertile and nourishing mother. Milk, in exegesis stood for the milk of Christian instruction, where it represents the initial stages of evangelical teaching before one can move onto solid food (cf. Hebrews 5:12).

The miniature displays knowledge of various iconographic traditions of depicting of the mother and child. The Kells image shows parallels with early Coptic (Christian Egyptian) images, which themselves engage with earlier non-Christian depictions of the Egyptian goddess Isis nursing Horus.

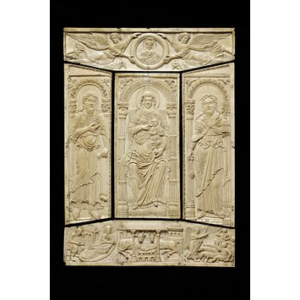

In early Christian monumental mosaic depictions of the Virgin and Child or in Carolingian ivories, Christ was presented sitting upright on Mary’s knee and both showed serious expressions as the Christ Child blessed those he looked upon with his fingers raised. The Book of Kells miniature instead has the Christ Child looking up at his mother, while reaching out to her with his left hand and embracing her arm with his right hand. As well as a God, we are also presented with a child seated on his mother’s lap. It seems that the illuminators of the Book of Kells had exposure to the iconographic models that favoured more intimate depictions of the mother and child.

Christ is depicted as having two left feet, while the Virgin is depicted as having two right feet. That representation is sometimes regarded as an error on the illuminators’ behalf, but this explanation seems unlikely, especially when one considers the high status of the Book of Kells and the immense care taken in its production as well as the spiritual symbolism of feet in the Bible. References to God’s feet or footstool allude to the divine power and glory (cf. Psalm 18:9, 132:6), while the washing of feet is regarded as the act of hospitality and humility (cf. Genesis 18:4, John 13:1-17).

Natasha Dukelow

Further reading

O’Dwyer, Peter, Mary: A History of Devotion in Ireland (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1998).

O’Reilly, Jennifer, ‘Introduction’, in Seán Connolly, trans., Bede on the Temple (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1995).

Rosenau, Helen, ‘The Prototype of the Virgin and Child in the Book of Kells’, Burlington Magazine 83 (1943), pp. 228-231.

Werner, Martin, ‘The Virgin and Child Miniature in the Book of Kells, Part I’, The Art Bulletin 54/ 1 (1972), pp. 1-23.

Werner, Martin, ‘The Virgin and Child Miniature in the Book of Kells, Part II’, The Art Bulletin 54/ 2 (1972), pp. 129-139.