The Book of Kells: Image and Text / The Four Evangelists

- Elaine Harrington

- May 30, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

The Four Evangelists

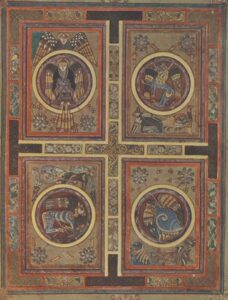

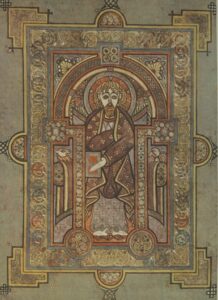

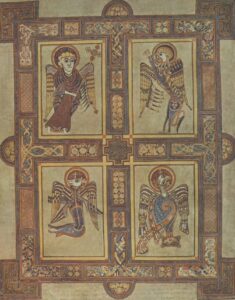

The most frequently found images in Insular Gospel manuscripts are those associated with the four Evangelists, depicted in portrait or symbol. In Gospel books, Evangelist portraits marked the beginning of each Gospel text, and their iconography derives from Late Antique author portraits. Two of the Evangelist portraits in the Book of Kells have survived, one representing Matthew, seen below, and one – John. It is believed that preceding each of the four Gospels, there was once a portrait of the corresponding Evangelist as well as a page that depicted all four Evangelist symbols, but unfortunately some of these have been lost.

The representations of the winged man, lion, ox and eagle correspond to the four Evangelist writers – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. These images are linked to the divine revelation witnessed by the Old Testament prophet Ezekiel. In a vision by the River Kebar, Ezekiel saw four living creatures descending from heaven, each with four faces and four wings (Ezekiel 1:4-16). Drawing on Ezekiel’s text, John the Evangelist described the four creatures with four faces and six wings standing next to the throne of the Almighty (Revelation 4:6-9).

The early Christian writers linked these creatures to the Evangelists in an attempt to emphasise the harmony between the Gospels. In the second century, Irenaeus (130-202) linked Matthew with the man, Mark with the eagle, Luke with the ox and John with the lion. However, the most influential interpretation was that provided by Jerome (347-420) in the text of the Plures fuisse which are the opening words of his commentary on Matthew. The text of the Plures fuisse was later copied in some Insular manuscripts.

Jerome based his pairing on the opening passages of each Gospel. According to Jerome, Matthews’s symbol is a man, as his Gospel opens with the description of Christ’s human descent: ‘The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham’ (Matthew 1:1). Mark is linked to a lion since his Gospel describes John the Baptist as a voice crying in the wilderness, which Jerome links with the roar of a lion: ‘A voice of one crying in the desert: Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight his paths’ (Mark 1:3). Luke is represented as an ox because his Gospel opens with a story of the priest Zachariah in the Temple: ‘There was in the days of Herod, the king of Judea, a certain priest named Zachary (Zachariah), of the course of Abia; and his wife was of the daughters of Aaron, and her name Elizabeth’ (Luke 1:5). Jerome connects that story to the Old Testament practice of using an ox in religious sacrifices (cf. Exodus 20:24). Finally, John is depicted as an eagle because at the beginning of his Gospel he immediately focuses on Christ’s divinity and his role in creation, rather than Christ’s earthly origins: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God’ (John 1:1). John is therefore like an eagle because it was believed that the eagle alone could fly towards the sun (a symbol of divinity) and look at it without being blinded. The Book of Kells features Jerome’s pairings.

Expanding on Jerome’s exegesis of the Evangelists and their relationship with the four creatures, Pope Gregory the Great (540-604) related each symbol to an event in Christ’s life. According to Gregory, the man symbolised Christ’s Incarnation, with significance placed on his humanity at birth. The ox represented the Passion of Christ due to the animal’s common use in the Old Testament sacrificial ceremonies, which prefigured Christ’s sacrifice. The lion stood for the Resurrection; according to the bestiary tradition a young lion was born either dead or asleep (details vary between traditions), but was awakened by the breath and roar of a parent. Isidore of Seville (560-636) writes: ‘when they [lions] bear their cubs, the cub is said to sleep for three days and nights, and then after that the roaring or growling of the father, making the den shake, as it were, is said to wake the sleeping cub’ (Etymologies 12.2.5, trans. Barney, 2006). Finally, the eagle soaring towards heaven was associated with the Ascension of Christ into heaven.

In pairing the four Evangelists with the beasts, exegetes created an exposition on the Gospel harmony that reflected the harmony of the natural world. The four Evangelists were related to the four cardinal directions, the four seasons, the four winds and the four elements that made the world and each human being, namely earth, fire, water and air. As argued by Jennifer O’Reilly, the four Gospels also reflected the quaternities of the Old Testament: the four rivers of Paradise or the four corners of the Ark of the Covenant. The number four was seen as harmonious and hence fitting to express the unified nature of the four Gospels. For this reason, the symbols are often depicted on a single page to represent distinctive accounts of the same truth.

The representations of the Evangelists as animals with particular characteristics also stem from bestiary traditions. A bestiary was a text that described real and imaginary animals or beasts and other animate and inanimate elements of the natural world. Characteristics of animals and their habitat were given symbolic significance and religious and moral meaning. If you are interested in finding out more about the bestiary tradition, then check out the Aberdeen Bestiary Project.

Kate O’Brien

Further reading

Barney, Stephen A., trans. and ed., The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

McGurk, Patrick, ‘The Gospel Text’, in Peter Fox, ed., The Book of Kells: MS 58, Trinity College Library Dublin (Lucerne: Facsimile Verlag, 1990), pp. 59-152.

O’Reilly, Jennifer, ‘Gospel Harmony and the Names of Christ in Insular Gospel Books’, in John Sharpe and Kimberly van Kampen, ed., The Bible as Book: The Manuscript Tradition (London: British Library, 1998), pp. 73-88.

O’Reilly, Jennifer, ‘Patristic and Insular Traditions of the Evangelists’, in Anna Maria Luiselli Fadda and Éamonn Ó Carragáin, ed., Le Isole Britanniche e Roma in Età Romanobarbarica (Rome: Herder, 1998), pp. 49-94.

Sullivan, Edward, The Book of Kells (London and New York: The Studio, 1914).

De Vinck, Aude, ‘An Early History of Portraiture: The Evangelist Portraits in Insular Gospel Books’ (MA thesis, University College Cork, 1994).