The Book of Kells: Image and Text / Opening Initials

- Elaine Harrington

- May 30, 2017

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

Opening Initials

The initial pages of each of the four Gospels in the Book of Kells are not at first glance easy to read. The alphabet used is the same one used by the majority of western countries today, but a different approach to the written word led to the creation of some unusually shaped letters that not only form words, but transmit symbolic meanings. Many of the pages were intentionally written to conceal letters, so the act of reading the text and finding its deeper meaning required focus and spiritual application. The obscuring of the letters in the Book of Kells would encourage the reader to spend time contemplating the deeper meaning of the passage.

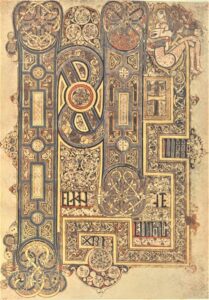

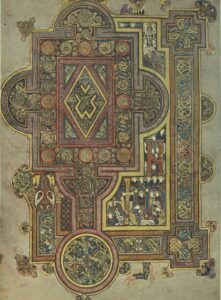

The Book of Kells conceals the opening words to each Gospel behind highly abstract, brightly coloured, interlocking letters. These letters are further decorated by the inclusion of men, animals and geometric shapes that are designed to act together with the text in illustrating the deeper meaning of the Gospel text. The initial page of the Gospel of Luke, folio 188r (below) contains the word Quoniam (‘forasmuch’) with the letter Q dominating over half of the page. Within the loop of the Q is set a large diamond-shaped lozenge. The lozenge has been interpreted as a reference to the world and the four cardinal directions. As argued by Jennifer O’Reilly, a lozenge shape in the Book of Kells also represents Christ. In expounding on the central position of the lozenge in the Kells Chi Rho page, she shows how the lozenge on that folio brings together the four corners of the world. The arms of the letter chi (X) simultaneously evoke the name of Christ and the Cross, as is discussed in another blog in this series devoted to the Chi Rho page.

In the bottom right of the Quoniam miniature there are small figures that populate the letters. George Bain interpreted the seated figure in the green robe as representing Christ, offering a chalice with the Eucharistic wine to several of the surrounding figures. This Eucharistic imagery taken in conjunction with the large lozenge appearing above, suggests that the path to eternal life is through Christ whose life is told in the Gospels. Another blog in this series will go into further detail about the reading and interpretation of the In principio (‘In the beginning’) initial on folio 292r that opens the Gospel of St John.

Connor White

Further reading

Bain, George, Celtic Art: The Methods of Construction (London: Constable, 1977).

Golden, Sean, ‘The Quoniam Page from the Book of Kells’, A Wake Newslitter 11 (1974), pp. 85-86.

King, Mike, ‘Diamonds are Forever, the Kilbroney Cross, the Book of Kells, and an Early Christian Symbol of the Resurrection’, Lecale Miscellany 19 (2001), pp. 3-13.

Markus, Robert Austin, Signs and Meanings. World and Text in Ancient Christianity (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996).

O’Reilly, Jennifer, ‘Patristic and Insular Traditions of the Evangelists: Exegesis and Iconography’, in Anna Maria Luiselli Fadda and Éamonn Ó Carragáin, ed., Le Isole Britanniche e Roma in Età Romanobarbarica (Rome: Herder, 1998), pp. 49-94.

Richardson, Hilary, ‘Themes in Eriugena’s Writings and Early Irish Art’, in James McEvoy and Michael Dunne, ed., History and Eschatology in John Scottus Eriugena and His Time: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Society for the Promotion of Eriugenian Studies Maynooth and Dublin, August 16-20, 2000 (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2002), pp. 261-280.