Culture Night: Shakespeare’s Sources & the Boole Library’s Resources

- Elaine Harrington

- October 5, 2016

The River-side welcomes this guest post from Dr Edel Semple, School of English on her experience using items from Special Collections’ early modern books collections in her Culture Night talk ‘Shakespeare’s Sources and Boole Library’s Resources.’

Shakespeare’s Sources and Boole Library’s Resources

Last month, I had the pleasure of giving a public lecture in the Boole Library as part of Culture Night 2016. My talk, “Shakespeare’s Sources and the Boole Library’s Resources”, sought to explore Shakespeare’s use of his sources and to give a general introduction to book history using the Library’s rare, early printed books. The talk was part of the British Council ‘Shakespeare Lives’ programme that commemorates the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death this year and is just one of several events in a year-long celebration of Shakespeare’s life and works at UCC and in universities around Ireland.

From the beginning, I should flag some limitations. Firstly, the talk and this blog post are in no way exhaustive explorations of all of Shakespeare’s sources; my research has been led by what early modern books are to be found in UCC’s Special Collections and so offers a selective discussion of some texts and their possible relevance to Shakespeare. Secondly, while Shakespeare and I are old friends, I am relatively new to the area of book history and thus any novice errors below are entirely my own. Nonetheless, in what follows, I hope to give a flavour of my talk which sought to highlight some of the early modern gems in Boole’s Special Collections and to offer a few insights into the pleasures of book history. In preparing for my talk, Elaine Harrington and the Special Collections staff were an invaluable source of information and support and I owe them many thanks.

Who is William Shakespeare?

In popular portrayals of William Shakespeare on film and TV – think Shakespeare in Love (1998) or the “The Shakespeare Code” episode of Doctor Who (2007) – the young Will is often shown as a genius in the making. These two screen iterations depict Will early in his career; he dashes about London, gets into scrapes, falls in love (or lust), and all of his experiences find their way into his plays. In their effort to create dramatic momentum, these screen depictions omit the fact that Shakespeare was an avid reader, a careful student of the classics, and a consumer of the latest works on the booksellers’ shelves. In the books that he read, bought and borrowed, Shakespeare found both incidental and foundational material for his writing.

Shakespeare’s London

Before exploring some of the books that Shakespeare used as sources of his plays, I opened my talk with two books that can give us a sense of Shakespeare’s world, of the sights and sounds that he experienced as an Elizabethan Londoner. John Stow’s Survey of London was first printed in 1598 and UCC’s Special Collections owns a fourth edition of the book, published in 1633. Stow’s Survey is a meticulously researched reference book on the history, topography, socio-economic conditions, and traditions of London. Such was its popularity, it was reprinted and enlarged for many years after its first iteration in 1598. As an example of the kind of information that Shakespeare could find in the book, or rather an example of an event he could have experienced in the city, I discussed Stow’s description of the “Sports and Pastimes” on offer to the average Londoner.

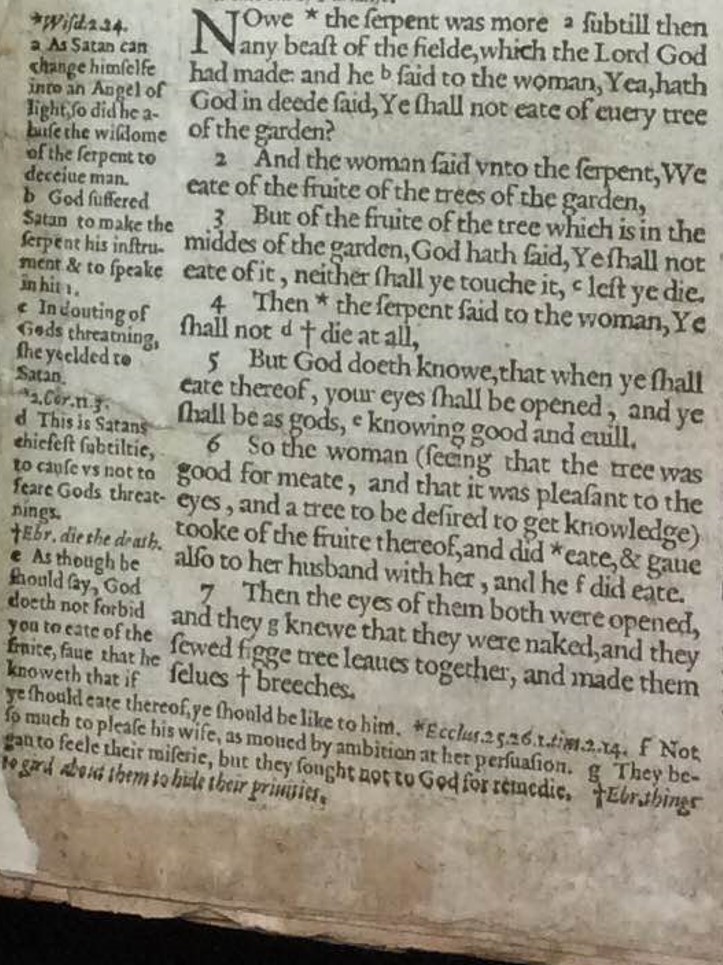

Shakespeare and The Bible

Using an early modern Bible, I discussed then the centrality of religion to early modern life and how details from, and the language of, the Bible may have found their way into Shakespeare. UCC’s Special Collections holds a Geneva Bible from 1587. The Catalogue’s notes on this item state that the “Old Testament is in the Geneva version, the earliest English bible printed in roman type and with verse divisions, first published at Geneva in 1560.” This book has a brown leather, blind-tooled cover (flowers and lacework patterns are discernable) and several pages have been repaired. I discussed the Bible’s typography (font, marginalia etc.), the uses of the images it contains (Eden, the parting of the Red Sea etc.) and why it is known as the “Breeches Bible” (see below the translation of Genesis, Chapter 3, verse 7).

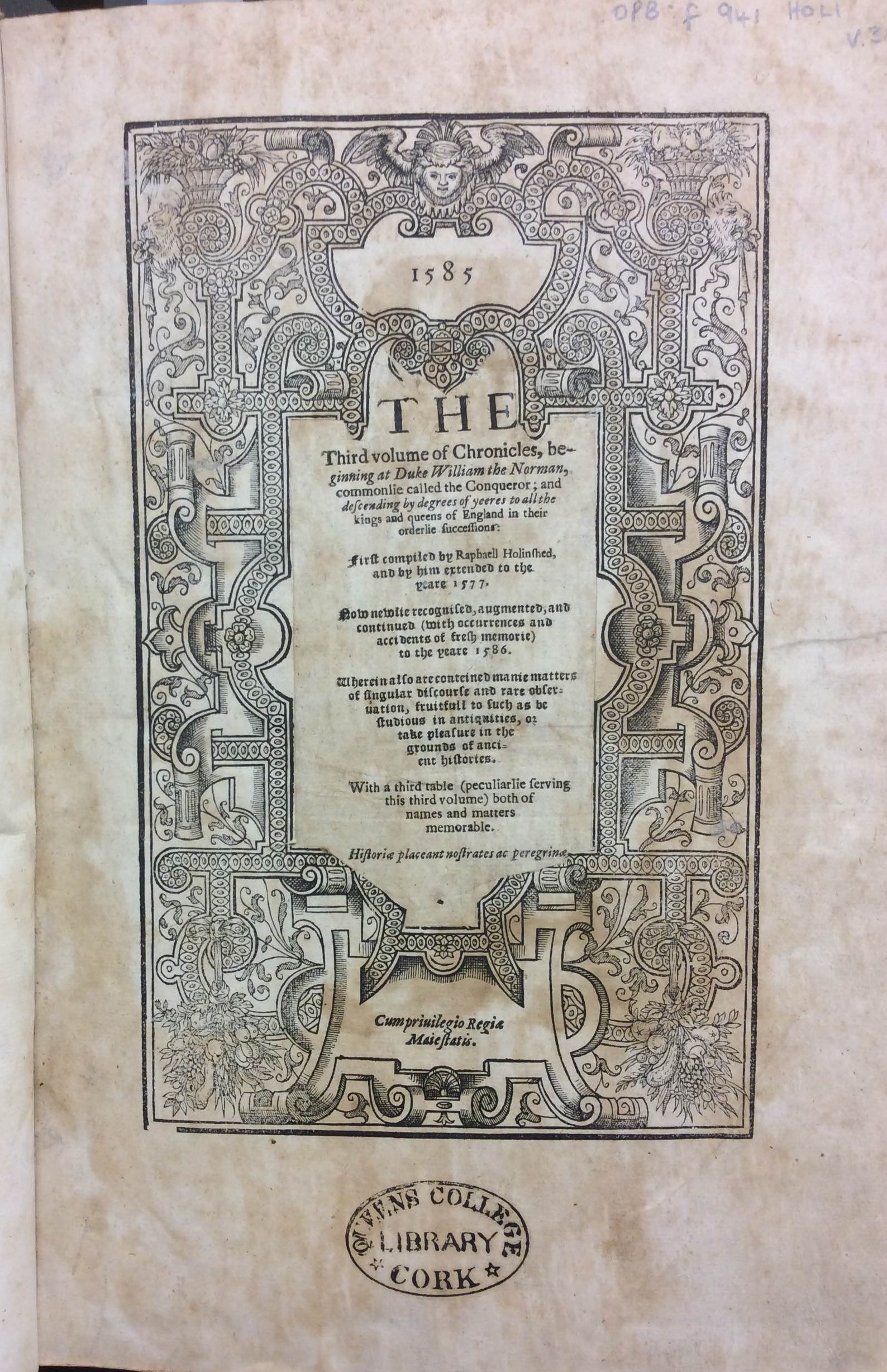

Shakespeare and Holinshed’s Chronicles

I next looked at Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, which has been long acknowledged as a key source for Shakespeare’s histories. This mammoth book was first published in two volumes in 1577, but the Boole Library owns the second edition which was printed in three volumes in 1586. I focused on Volume 3 of Holinshed’s Chronicles as here could be found the sources of several plays including Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, and Richard III. Having examined the tales of these monarchs, however, my attention was caught by the volume’s title page.

Holding a light behind the page, I could see that three pages actually made up the title page: the text in the centre was a small page sandwiched between the blank page at the back, and the image that framed it at the front. Why carry out a cut-and-paste job such as this? Did the central panel of text belong with this book, that is, did it accurately describe the contents of Volume 3? And where did the framing image come from?

In search of answers I consulted other copies of Volume 3 of the 1586 edition of Holinshed on the database Early English Books Online. Here I found that the UCC Library copy was quite different; other copies had a title page showing various kings (David, Solomon, William the Conqueror etc.) and at the bottom of the box frame was Elizabeth I. The image that this refers to is here. The central panel of information however was exactly the same as the UCC Holinshed. Thus, the ornate frame did not belong with the Holinshed but the information was correct. I then worked through the title pages to discover that the ornate frame was actually from “The Description of Scotland” (Volume 2, second edition). The image this refers to is here. This framing image clearly comes from the second edition, as a small mermaid and the tag “God save the Queene” appear in the 1577 edition but do not appear on the title page from the later edition.

Following this, I checked the Library’s Volume 1 and Volume 2 of Holinshed’s Chronicles to see if the page had been cut from either of these copies. Both volumes are bound together in leather with marbled end-papers and a notable manuscript comment at the opening of Volume 1 proudly declares: “complete in two volumes – collated & found perfect. Perhaps without exception the finest copy in Great Britain.” As this remark suggests, all of the titlepages were intact and were in good condition. (Incidentally, investigating Volume 1 and 2 also enabled me to identify a watermark in some pages and to find some scraps of paper – half an old Library call card for example – tucked in the pages, but with time constraints, watermarks and found objects were a subject I had to omit from the talk.) Thus, the owner of Volume 3 must have got his/her hands on another copy of Holinshed’s Volume 2 (second edition) and took the ornate titlepage image from it. I can only speculate as to why the owner cut and pasted the “The Description of Scotland” titlepage to make a new titlepage for Volume 3 – perhaps the owner preferred the ornate style, or perhaps she/he wished to make Volume 3 similar in appearance to the titlepages of the 1577 edition of Holinshed, which are the same save for the mermaid and tag.

Shakespeare and Pliny’s The History of the World

Shakespeare gleaned details for his tragedies from various sources. In Pliny’s The History of the World (1601), for example, Shakespeare found descriptions of Eastern lands, people, and customs and these found their way into Othello (1603), written soon after the Pliny was first published. For example, there are echoes of Pliny in Act 1 Scene 3 where Othello informs the Venetians that the tales of his adventures and the exotic sights to be seen in far off lands, such as the strange creatures like the “Cannibals that each other eat, / The Anthropophagi and men whose heads / Do grow beneath their shoulders”, appealed to Desdemona.

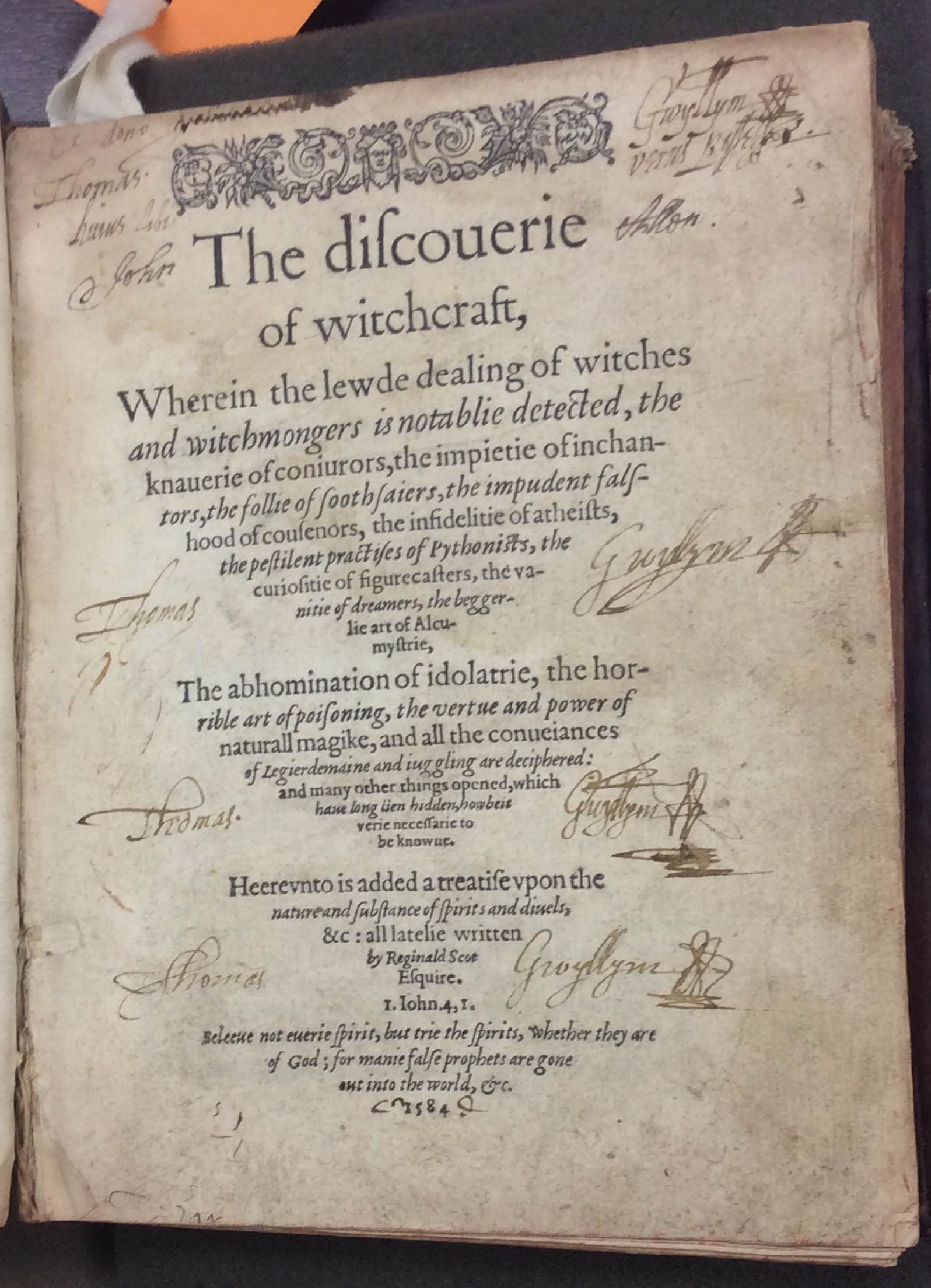

Shakespeare and Reginald Scot’s The Discoveries of Witchcraft

Shakespeare undoubtedly drew on popular folklore for the weird sisters in Macbeth, but he also consulted Reginald Scot’s The Discoveries of Witchcraft (1584). In addition, this book may have yielded him information on the sprite Robin Goodfellow, now better known as Puck, the mischievous fairy in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In discussing the Library’s copy of Discoveries, I noted the volume’s size (quarto) and ownership history. One “Thomas Gwyllym” has written his name on the titlepage, repeatedly in fact, and his name appears at several points inside the volume. Gwyllym may have been using the blank space to practice his signature but he may also have wanted to ensure that one “John Allen”, who had borrowed the book, returned it to its rightful owner.

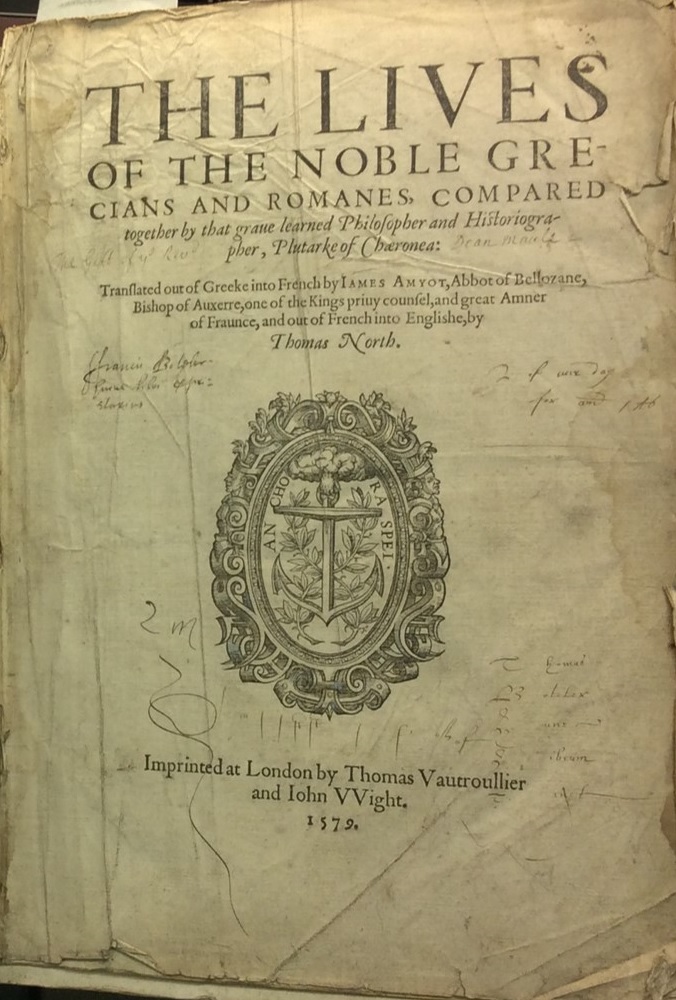

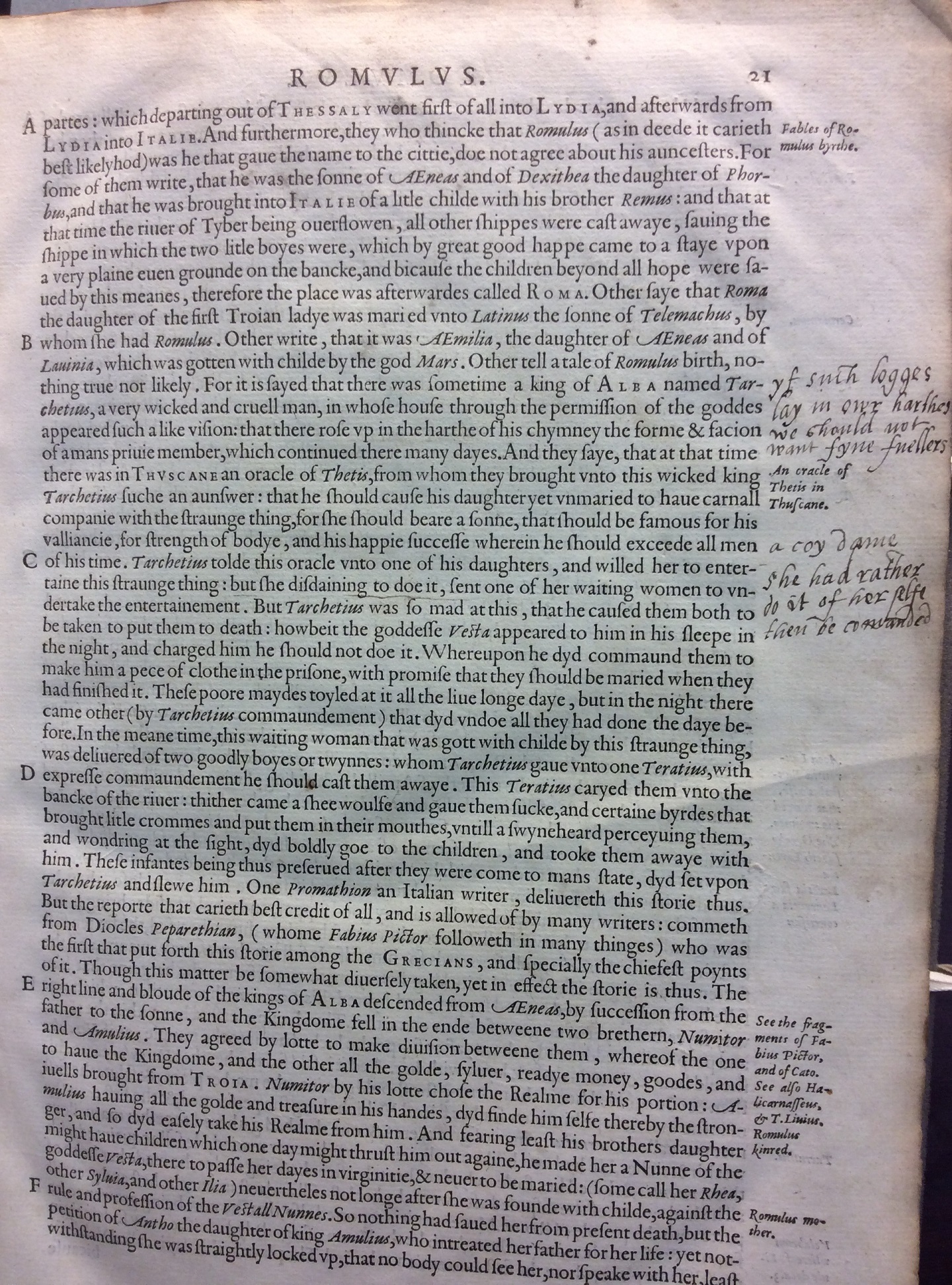

Shakespeare and Plutach’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans

Shakespeare used Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (1579) as a source for several tragedies, but in my talk I focused on Antony and Cleopatra. I discussed genre and style using as an example Plutarch’s description of Antony and Cleopatra’s first meeting on the river Cydnus and from the play Enobarbus’ “The barge she sat in, like a burnished throne” speech from Act 2 Scene 2. Turning to book history, I noted that the UCC copy of Plutarch’s Lives is from the Green Coat School collection. The Green Coat School was a charitable Church of Ireland school founded in 1715 in Shandon with the aim of educating impoverished children. According to a note on the titlepage, the volume was a “gift of ye Revd Dean Maule”, the School’s founder. On the back board, a strip of medieval vellum, about an inch wide, has been used as a strengthener. Sometimes luck can play a role in research questions and I was fortunate that Dr Jason Harris of the School of History passed through Special Collections and offered his opinion on this medieval manuscript. From his examination of the vellum strip, Dr Harris believes that the manuscript is likely from the fourteenth century and is from a medical or scientific text. Elsewhere in Lives, a reader has commented on some passages of text. The word “not” appears in the margin beside Roman troop numbers; perhaps the reader was a scholar noting such important data, or wished to learn off these details (impress your friends with facts and figures!). The same reader has also made two bawdy comments on a story in the life of Romulus.

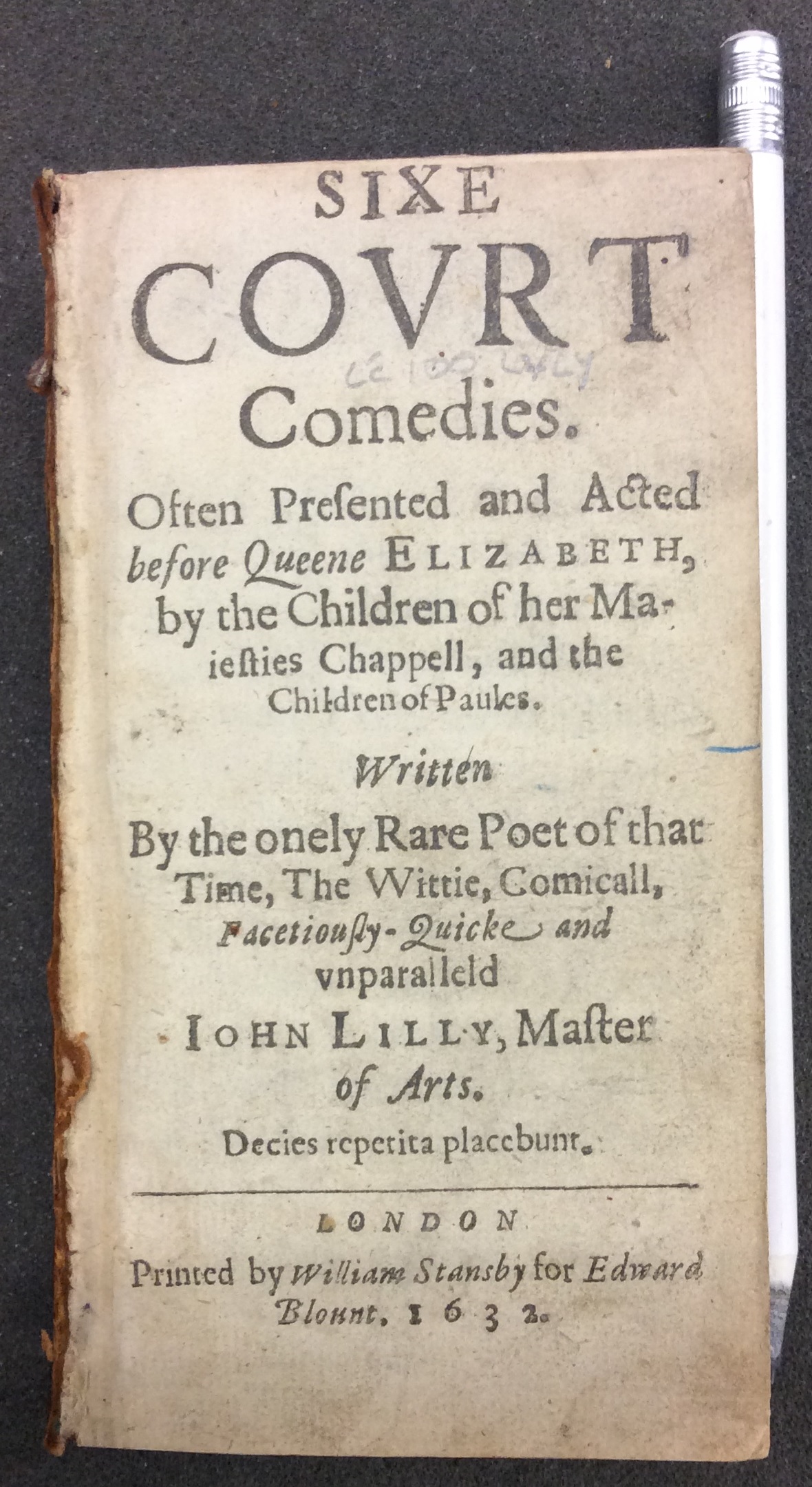

Shakespeare and John Lilly’s Sixe Court Comedies

For influences on Shakespeare’s comedies I turned to John Lilly’s Sixe Court Comedies (1632). Having taught Lilly for the first time earlier this year, I am a new convert to his work. Both as a text to read or a play to be seen, Lilly’s work is funny and engaging and it is little wonder that there is a renewed scholarly interest in Lilly in recent years. The Special Collections copy of Lilly’s Comedies is a neat volume, ideally sized to slip into a pocket. As the Library’s volume is clean and in good condition, I focused on exploring the book’s paratexts.

The title page does much to sell Lilly to its potential consumer; the capitalised words in the title “SIXE COURT Comedies” jump out to catch the eye (a whole six plays and ones performed at court no less!), we’re told that the plays were often performed by the elite boys’ companies, and the author is described as “Rare […] Wittie, Comicall, Facetiously-Quicke and unparalled”. If that is not enough, a Latin tag informs the learned reader that although you might read the book ten times, it will still give pleasure. Inside the slim volume, in the Dedicatory Epistle, the printer Blount even tries his hand at imitating the witty Lilly; he tells us that the Spring is upon us and so he presents us with a lily (this book) and its precious cargo: “sixe ingots of refined invention; richer than Gold”. For all the hyperbolae, this early modern PR would surely have charmed even the most reluctant of prospective buyers. To close my talk, I looked at how Shakespeare was influenced by Lilly’s Galatea (or Gallathea) (written c.1584). Traces of Lilly’s euphuistic style can be found across Shakespeare’s comedies of romance and in particular the pastoral setting, style, and concerns of Galatea appear in various guises in As You Like It, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Twelfth Night. Further, Galatea’s transvestite heroines Galatea and Phillida are clearly the forebears of Shakespeare’s Rosalind, Viola, and Portia.

Further Events

Further events for Shakespeare 400 are planned to take place in UCC, on October 18th and on November 14th-15th, and in several universities around Ireland over the coming months. Details will be available on the “Shakespeare in Ireland” blog and the UCC School of English website in due course. Information on these and related events can also be found on the British Council’s “Shakespeare Lives” website.

Bibliography

The Bible. London: Imprinted by Christopher Barker, Printer to the Queenes most excellent Maiestie, 1587.

Holinshed, Raphael. The … Chronicles Comprising the Description and Historie of England, the Description and Historie of Ireland, the Description and Historie of Scotland. [London] : Finished at the expenses of John Harison, George Bishop, Rafe Newberie, Henrie Denham, and Thomas Woodcocke, 1586-87].

Holinshed, Raphael. The Third Volume of Chronicles, beginning at duke William the Norman, commonlie called the Conqueror; and descending by degrees of yeeres to all the kingsand queenes of England in their orderlie successions. 1586. Copy from the Huntington.

Holinshed, Raphael. The Second volume of Chronicles: Conteining the description, conquest, inhabitation, and troblesome estate of Ireland; first collected by Raphaell Holinshed; and now newlie recognised, augmented, and continued from the death of king Henriethe eight vntill this present time of sir Iohn Perot knight, lord deputie. 1586. Copy from the Huntington.

Lilly, John. Sixe Court Comedies: often presented and acted before Queene Elizabeth, by the Children of Her Majesties Chappell, and the Children of Paules. London: Printed by William Stansby for Edward Blount, 1632.

Pliny. The Historie of the World: Commonly Called the Natvrall Historie of C. Plinivs Secvndvs. Trans. into English by Philemon Holland. London: A. Islip, 1601.

Scot, Reginald. The Discouerie of Witchcraft: Wherein the Lewde Dealing of Witches and Witchmongers is Notablie Detected. London: Imprinted by William Brome, 1584.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays and Poems of William Shakspeare: in sixteen volumes. Dublin: Printed by John Exshaw, 1794.

Stow, John. The Survey of London: Contayning the Originall, Increase, Moderne Estate, and Government of That City, Methodically Set Downe, with a Memoriall of Those Famouser Acts of Charity, which for Publicke and Pious Uses Have Beene Bestowed by Many Worshipfull Citizens and Benefactors. London: Printed by Elizabeth Pvrslovv, and are to be sold by Nicholas Bovrne …, 1633.