Lost at Sea: Thomas O’Brien Butler and RMS Lusitania

- Elaine Harrington

- May 20, 2015

The River-side welcomes Garret Cahill’s guest post on Thomas O’Brien Butler and RMS Lusitania.

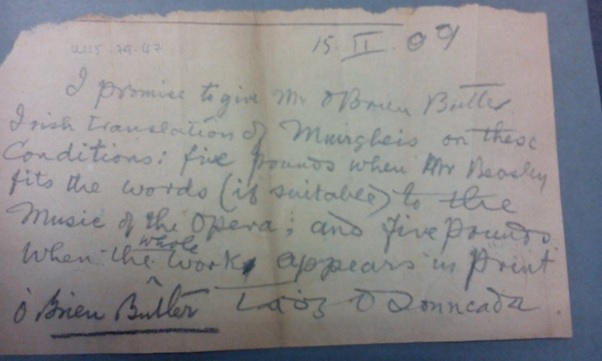

Countless users of the Special Collections in the Boole Library are familiar with the name ‘Tórna’, the pen-name of Tadhg Ó Donnchadha (1874-1949), Professor of Irish at University College Cork from 1916. His extensive library forms an indispensable part of the working collection in the Q-1 reading room, and is a testament to the breadth of his intellectual interests. However, the Boole Library also holds his substantial private papers, and among these is an interesting document dating from February 1909 and written on what appears to be a torn page of a pocket diary [U115/79/47]:

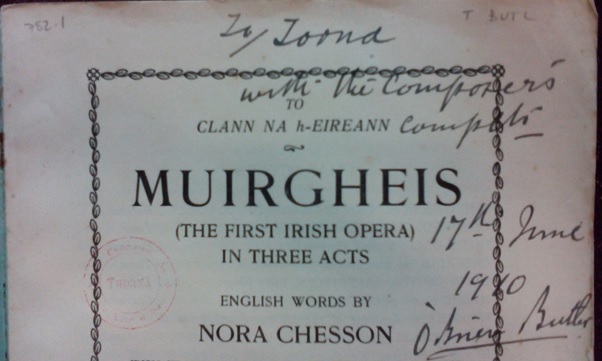

A further item, this time in the Torna library itself, sheds more light on this miniature ‘contract’:

This is the vocal score of the Irish composer Thomas O’Brien Butler’s opera Muirghéis, inscribed to Tórna “with the composer’s complts, 17 June 1910.” As the title page notes, the libretto was written by Nora Chesson, with the Irish words provided by Tadhg Ó Donnchadha. His papers, unfortunately, do not confirm if he received his fee on publication!

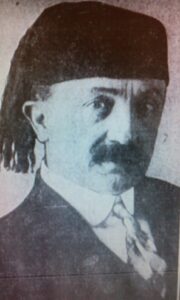

Thomas O’Brien Butler

Thomas Butler (the O’Brien came later) was born in Cahersiveen, Co Kerry on 3 November 1861, youngest of a large family born to Pierce Butler (c.1804-1873), a draper and butter merchant in the village, and his wife Ellen Webb (c.1818-1876). Thomas was educated at St Colman’s College, Fermoy, and then held a number of Catholic church organist positions, including briefly in Youghal in 1886 and for two years in Parsonstown (now Birr), Co Offaly. Adopting the name ‘Whitwell Butler’ (a common Christian name among his ancestors), he emigrated to New Zealand, where one of his married sisters was living, and worked for a couple of years as a music teacher and choirmaster. He composed a few songs, mostly performed locally, though one, “Fate’s Decree” was briefly taken up by the Italian singer Felicina Cuttica. Leaving New Zealand in late 1895, Butler travelled to India and then studied music privately in Milan, with Alberto Giovannini (1842-1903) before enrolling for three terms at the Royal College of Music in London in 1897-98. He was now in his mid-30s and hardly a typical student, but the study appears to have emboldened him to compose more ambitious music, and it is also likely that his spell in London brought him into contact with the fledgling Irish literary revival. At all events, he changed his name once more to ‘O’Brien Butler’ and returned to Ireland. Holidaying in his native county, the Kerry Sentinel of 16th August 1899 noted that he was “at present working at an Irish opera.”

Composing Muirghéis

The composition of Muirghéis (The Sea Swan) took several years, and Butler endeavoured to interest the prime movers of the Revival in his work. Some entries from the diaries of Lady Gregory are of interest here. She had arrived in London from a visit to Paris at the beginning of May 1900, and – as usual – made her way to see her friend William Butler Yeats:

“He [Yeats] says there is a new recruit to the Celtic movement, a musician, O’Brien Butler, who is writing an opera, & wants a libretto, & wants a cottage in Co Galway, where he can work – [George] Moore had spent 2 hours listening to him & said he was better than Stanford, & was delighted – Yeats had sent him to see Nora Hopper, & to ask her to do a libretto.”

The following day:

“Then to tea with Yeats to meet O’Brien Butler – didn’t think him very intelligent or attractive, but asked him for a few days when he comes over that he may look for a cottage…”

Finally, on 7 May 1900:

“Loaded my luggage at the Station & dined with Yeats & G. Moore – The latter says O’Brien Butler is very amateurish, & that it was only his general amiability since his conversion to Ireland that made him compliment him or sit two hours with him during which he was bored to death – However Miss Hopper arrived after dinner & they pounded out the libretto…”

Though the libretto was the work of Nora Hopper (later Chesson) with some help from George Moore, the story appears to have been Butler’s own work. The preface to the score outlines the plot.

The Plot of Muirghéis

The scene of the opera is Waterville on the coast of Kerry, Ireland at the dawn of Christianity. Muirghéis and her foster-sister Maire are both in love with Diarmuid, a neighbouring chieftain. Diarmuid returns the love of Muirgheis, and Maire filled with jealous hate, calls upon Donn of the Sand Hills, a fairy king of the seacoast, to carry off Muirghéis to Tir-na-n’Og (Fairyland). Donn consents, but warns Maire that if she asks another request of him it will involve her own death. He gives Maire an enchanted branch of quicken and tells her that if Muirghéis touches it even with finger tips she comes immediately under his power. Maire weaves this branch into a wedding wreath which she places on Muirghéis’ head at the Marriage feast, whereupon Muirghéis is carried off by Donn. Diarmuid is in a passion of despair, but refuses to be comforted by Maire, who seeing her efforts fruitless, is stricken with remorse.

She again calls upon Donn, knowing the penalty she incurs, and requests him to restore Muirghéis. Donn consents, but enraged at the action of Maire, he dooms her to be changed after death into a sea-wave. Muirghéis is restored, but her mind is blank, for it is a tradition in Kerry that if people return from Fairyland they are soulless and without memory until they shed tears. Diarmuid approaches, but she does not greet him. All her friends try in vain to awaken her recollection. At length the name of Maire seems to penetrate the spell. The dead body of her foster-sister is brought in and Muirghéis bursts into tears and her soul returns.

Further Thoughts on Muirghéis

The tale is certainly redolent of the Celtic Twilight, and it may be that this is why Yeats suggested Nora Hopper (1871-1906) as a possible librettist, since despite never having been to Ireland, she had written considerable poetry of a sub-Yeatsian kind and he presumably felt she would be sympathetic to the atmosphere of the story. The completed libretto was published by Nora Chesson in her 1902 collection Aquamarines, a year before the opera itself was produced. Butler must surely have hoped that Yeats himself might have been the one to provide the text, but neither Yeats nor Lady Gregory were especially taken with the composer. Indeed, poor Butler does not appear to have made a hugely favourable impression on his contemporaries. A couple of years later, J.M. Synge wrote to Lady Gregory from Kingstown:

As Michele Esposito (1855-1929) was probably the most important musician working in Dublin at this time, this is not very flattering. Perhaps even less so is Yeats’s own opinion of Butler, given in two of his letters to Lady Gregory (the inaccurate spelling is characteristic):

“Woburn Buildings, 5 June 1900:

O’Brien Butler turned up last night. He goes to Dublin on the 13th he thinks & will be there a week. He wanted I imagine to travel over with me, but that was out of the question & I said something vague about going with friends. He also wanted to know where I would stay in Dublin but I would not tell him (I said I was uncertain where) for I shall be there with Miss Gonne … I dont know that I greatly want to travell down to Galway with him either for he knows little of anything but music [but that I may do]. I dare say a musical person would find him interesting abundantly. I think Miss Hopper likes him, & I hear praises of his setting of Moll Macgee.” [Collected Letters of WB Yeats II, 537-538]

“Woburn Buildings, 27 November 1901:

I forgot to tell you that when I got back here I found that O’Brien Butler had been enquiring about the floor under me. You will remember his desire to go & live near you and Martyn. I told Mrs Old that I wont have him in the house. To do him justice he said he would have to ask my leave.” [Collected Letters of WB Yeats III, 130]

Producing Muirghéis

However, if the Abbey Theatre directors were underwhelmed, Butler found greater support within the Gaelic League, and in particular from the Keating Branch (Craobh an Chéitinnigh), of which Tórna had been a founding member. It is likely that Butler and the Irish scholar met at this time, since Tórna was then living in Dublin, where he was editor of Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge.

In order to raise funds for the proposed production of Muirghéis, two concerts of excerpts were held in the Antient Concert Rooms on Brunswick (now Pearse) Street in April and June 1902. The Gaelic League journal An Claidheamh Soluis noted before the second recital:

“The opera is the first ever written in Irish words or in Irish music, and for that reason alone should demand support. The composer has come to the Gaelic League with his work, and the Gaelic Leaguers of Dublin should support him…” (7 June 1902).

Though he did not become editor until the following year, these remarks are redolent of the tone of Patrick Pearse, and when a committee was formed to ensure the full production of the opera, it is not surprising that Pearse was a member, along with Edward Martyn and Eoin Mac Néill.

With the organisation of the League behind him, Butler succeeded in mounting Muirghéis for a week in December 1903 at the Theatre Royal in Dublin. Present on the opening night was the inveterate theatre-goer and Abbey architect Joseph Holloway, whose diary constitutes an invaluable source of information and gossip for the period. In it he noted:

“Frankly I did not think much of O’Brien Butler’s ‘First Irish Grand Opera’ Muirghéis (produced by local artists at the Royal for the first time on any stage last night). Somehow or other I got it into my head that the opera was to be sung in Gaelic, but before the first Act had run its course, I discovered by accident that the singers were supposed to be vocalising English words. Their enunciation was very defective…”

As we have seen, it was indeed intended that the opera should be given in Irish and it is not clear why this did not happen. Though the response to the opera was mixed, to say the least, Butler was undeterred in his attempts to promote it, unsuccessfully mooting a revival in 1907, and achieving the publication of the vocal score by the prestigious Leipzig firm of Breitkopf and Härtel in 1910. The appearance of the score occasioned some further attention, in particular from Edward Martyn, who had championed Butler’s music from the beginning and had also invited him to stay in his home, Tullira Castle in Co Galway.

Butler & America

But it was in the United States that Butler hoped for greater success, and he arrived in New York just before Christmas 1914 to attempt to raise interest among American impresarios. During his stay he arranged a concert of some of his music at the Aeolian Hall on 19th April, as well as having his photograph taken in some exotic headgear!

Having concluded his business without, it appears, any great success, he boarded the RMS Lusitania to return to Ireland on 1 May 1915. As is well known, the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine off the Old Head of Kinsale six days later, and Butler was one of the almost 1200 passengers and crew who died as a result. His body was never recovered, and the full score of Muirghéis is presumed lost with him. A century later, as varied commemorations of the sinking of the Lusitania take place, it is surely appropriate to remember the career of a significant, if largely forgotten, participant in the cultural revival of Ireland and his links to our collections here.

An exhibition on the Lusitania which includes Torna’s copy of Muirghéis will run in the Boole Library until the end of June 2015.

Notes

Tadhg Ó Donnchadha’s papers (U.115) are held in Special Collections. To request further information about them or to view them please contact specialcollectionsarchives@ucc.ie.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography contains further information on the people in this post.

Bibliography

An Claidheamh Soluis. (1902)

Butler, O’Brien. Muirgheis: The First Irish Opera, in three acts. English words by N. Chesson; Irish translation by Thadgh O’Donoghue; music composed by O’Brien Butler. New York: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1910.

Holloway, Joseph. Impressions of a Dublin Playgoer, 8 December 1903. NLI MS 1801.

Lady Gregory. Lady Gregory’s Diaries 1892 – 1902. Ed & introd. James Pethica. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1996.

Synge, John Millington. The Collected Letters of John Millington Synge. 2 vols. Ed. Ann Saddlemyer. Oxford: Clarendon P; New York: OUP, 1983-1984.

Tadhg Ó Donnchadha’s papers (U.115)

Yeats, WB. The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats. 4 vols. Ed. John Kelly. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: OUP, 1986-.

![Letter from Synge to Lady Gregory [28 Sept 1905] p.134 Vol 1](https://theriverside.ucc.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Synge-Esposito-1024x615.jpg)