Mapping Cork: Trade, Culture and Politics in Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland / From Rivers to Roads

- Elaine Harrington

- May 20, 2020

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

Mapping Cork: From Rivers to Roads

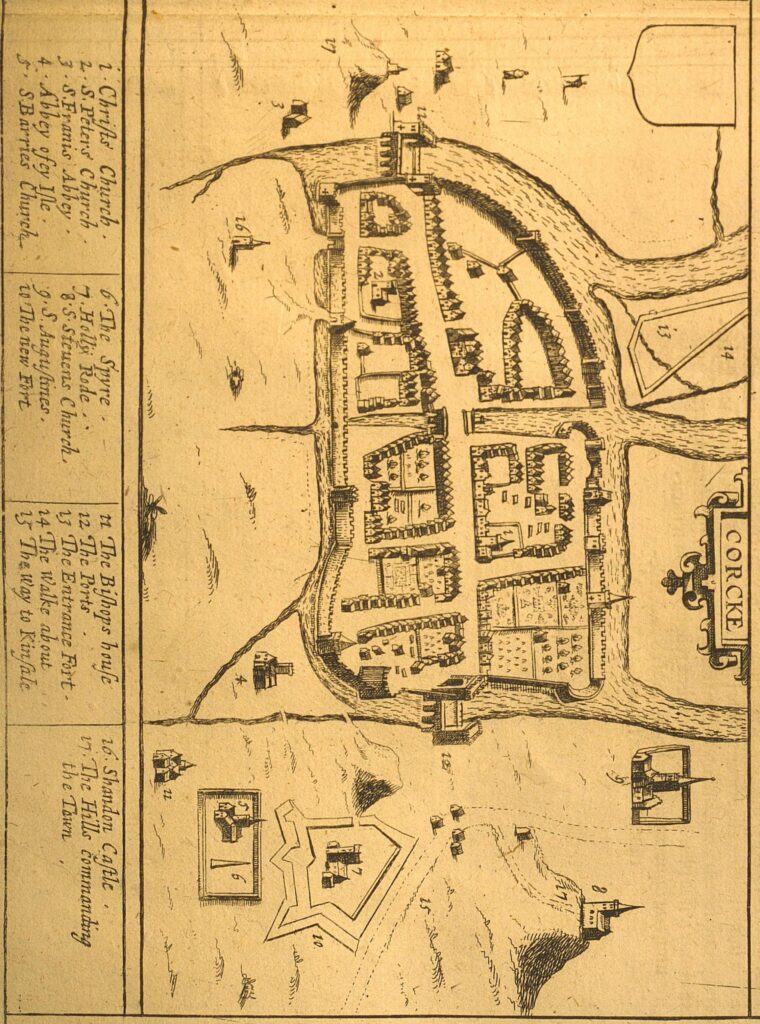

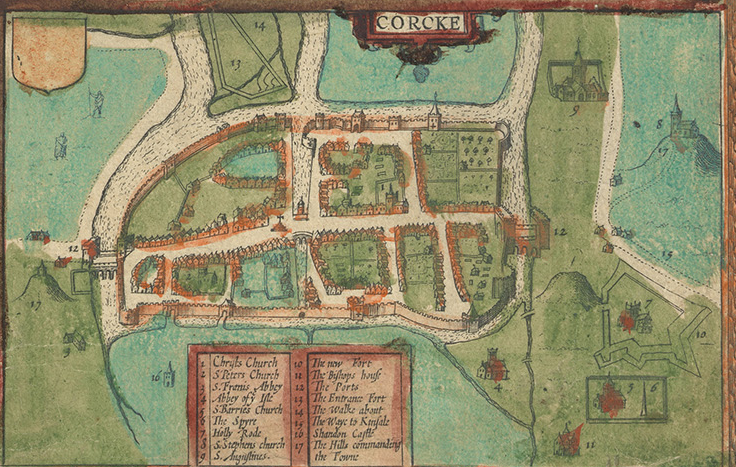

Like other Irish cities represented in the Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Cork was established as a harbour at the mouth of a river. However, more than these cities, Cork has been defined by its unique placement on the river Lee. Built originally on two islands within the river, the city has made effective use of the waterways throughout its history, whether for defence or commerce. Indeed, as a walled medieval town established on these two islands, Cork benefitted from having a waterway which flowed inside the walls. This allowed merchant ships to dock safely within the protection of the walls, instead of in the open water, which encouraged the growth of a wealthy merchant class and international trade. A 1306 will of Cork merchant, John de Wynchedon, is a witness to the wealth of the city’s medieval merchants. John’s generosity ensured the wellbeing of his family after his death, but he also took great care to offer his benefactions to over a dozen of Cork’s churches for the salvation of his soul as well as to the marginalized groups, including the poor and the lepers.

However, the map of ‘Corcke’ in the Civitates, alongside other early modern maps of the city, reveals an even more subtle fashion in which the riverways shaped Cork. The map is oriented in an east-west direction, but by reorienting the map north-south and by paying attention to the channels of the river, features of present-day Cork become identifiable. It is also possible to spot the modern street patterns, many of which exist above the earlier river paths.

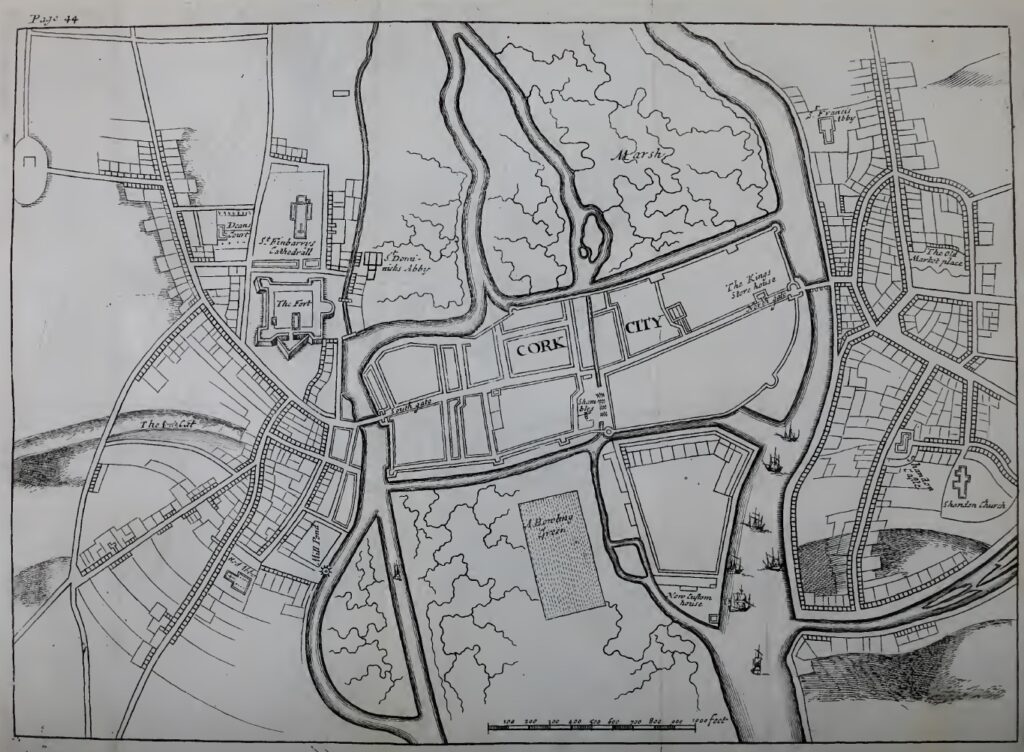

In the early maps of Cork, from 1600 to 1650, the city is depicted as based on two islands, separated by a waterway running across town and dividing the city into the north and south sides. By 1690, this inlet no longer appeared on the maps, a road now ran east-west through the walled town, where it formerly was. This road was situated roughly where the modern Washington Street is located.

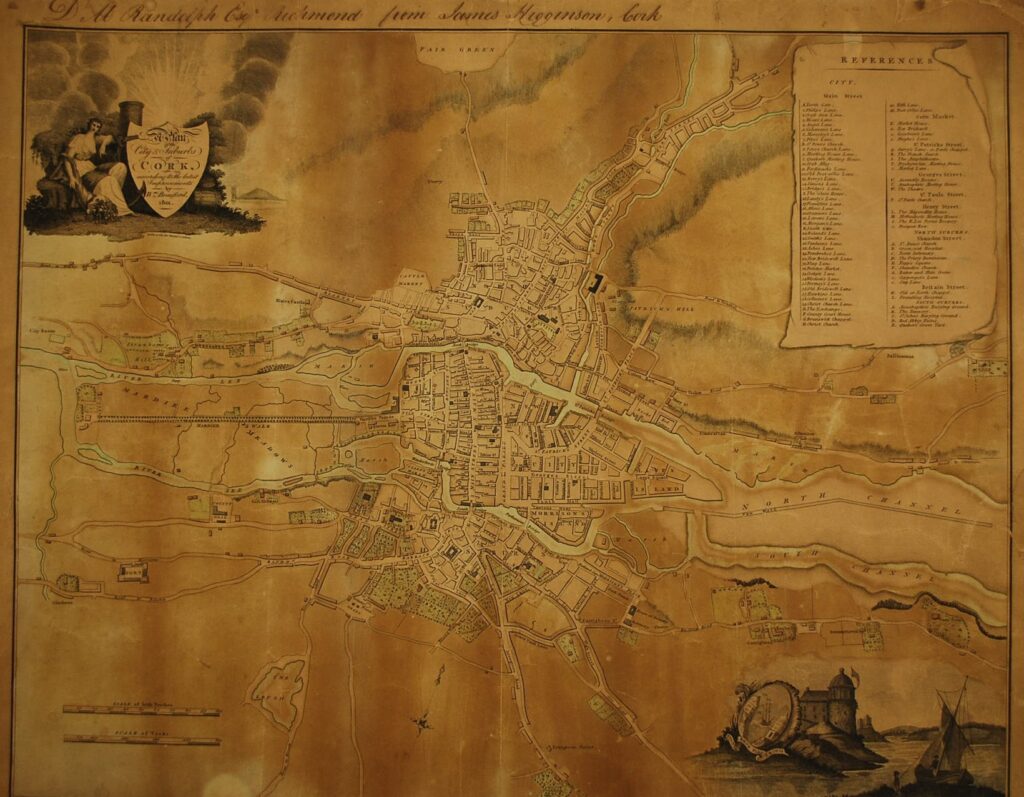

By the late seventeenth century the city had also begun expanding outside of the walls, into what would eventually become known as the Huguenot Quarter, north of present-day St Patrick’s Street. However, at that time water still flowed in channels, which correspond to the Grand Parade, St Patrick’s Street, Coal Quay Market, South Mall and the sections of Washington Street that were located outside the walls of the medieval city. Roughly fifty years later, the area presently known as Oliver Plunkett Street began to be developed; quays lined the waterside on the Grand Parade and the curve which later became St Patrick’s Street. The water channels were covered over between the Grand Parade and the Coal Quay Market. On the map of Cork from 1750, quays are also clearly evident along a spur of the river alongside, where the Opera House and Crawford Art Gallery now exist.

By the 1770s, most of the waterways beneath the present-day Grand Parade and the Coal Quay Market were covered, which greatly reduced the expanse of waterfront quays available in the eastern half of the city. The overall shape of modern Cork’s central island was established, the city’s development had already reached the easternmost point of the island at the confluence between the north and south branches of the river Lee. In the western part, the city had not yet expanded far beyond the medieval walls; Abbey Island, located to the south-west and near St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, was still surrounded by the separate channels of the river.

By 1801, St Patrick’s Street had completely replaced the older waterway, as had the Grand Parade, and much of the South Mall. Small spurs of water still remained at the locations of the Coal Quay Market and the Emmett Place, and water channels still separated Abbey Island from the rest of the city centre. The city was expanding both north and south of the river, and was beginning to grow westward.

By tracing the water paths shown in the early maps of Cork, such as that found within the Civitates Orbis Terrarum, it is possible to recognize the locations of many modern landmarks, because of the unique fashion in which the riverways were directly covered and converted into roads.

Emmanuel Alden

Further reading

Crowley, John and Murphy, Michael, Atlas of Cork City (Cork, 2005).

Johnson, Gina, The Laneways of Medieval Cork: Study Carried out as Part of Cork City Council’s Major Initiative (Cork, 2002).

O’Callaghan, Antóin, Cork’s St Patrick’s Street: A History (Cork, 2010).

O’Flanagan, Patrick and Buttimer, Cornelius G, eds., Cork History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County (Dublin, 1993).

O’Sullivan, D., ‘The Testament of John de Wynchedon of Cork, Anno 1306’, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 61 (1956), 75-88.