Representing Historical Grief

- Barbara Diener

- October 3, 2024

Alen MacWeeney’s Northern Ireland photographs

written by Chiara Alessio

Alen MacWeeney Collection

The Northern Ireland series, shot by Irish contemporary photographer Alen MacWeeney (born 1939), resides in Special Collections and Archives in UCC’s Boole Library as part of the Alen MacWeeney Collection. It contains fifty-nine vintage gelatin silver prints depicting the Troubles during 1971. A Dubliner, MacWeeney immigrated to New York City in the 1960s, but came back to Ireland to depict border cities like Belfast and Derry in their most atrocious moments. After working as apprentice to renowned fashion photographer Richard Avedon, MacWeeney quickly found his own passion and style in Irish culture, people, and landscape. The photos are plentiful and diverse, showing posing IRA members with their faces squished against make-shift mesh masks, firefighters running to extinguish fires between the rubble left behind from the conflict, and the haunting personal and close-up portraits of people grieving their loved ones who perished during those times. It is exactly the concept of Grief that is the most, ever-present sensation that emanates from the images; the grief brought from the sensation of feeling lost, divided, fragmented from the inside out, as a cohort of the people of Northern Ireland saw their identities and habitats threatened by a colonising force. The struggle to preserve oneself, personally and culturally, between explosions, bonfires and raids is excruciating. Northern Ireland is more than a documentary analysis, but also a cultural, communal and personal outlook, giving insight on how the Irish identity was shaped and changed from the conflict.

Left: [Firefighters at work at a bombing site], 1971. Right: Grieving family-son/husband killed in raid-Falls Road area, 1971. Photographs above by Alen MacWeeney. Courtesy University College Cork © 2022 (All Rights Reserved).

On Documenting Historical Trauma

Alen MacWeeney’s self-extraction and emigration to the US allowed for him to return and capture this conflict from a point of view that was both removed and emotionally engaged at the same time. Fractured and destroyed, MacWeeney shows collective trauma through items that have morphed from their original form, such as a double-decker bus, which is depicted as nothing more than a melted steel skeleton, after it was set ablaze. Similarly, MacWeeney depicts the dark soot slithering out of the windows of a house after a fire, or somebody frantically leaning inside a burning car to retrieve personal belongings, or again a pile of bricks left as a memory of houses, buildings or businesses once standing.

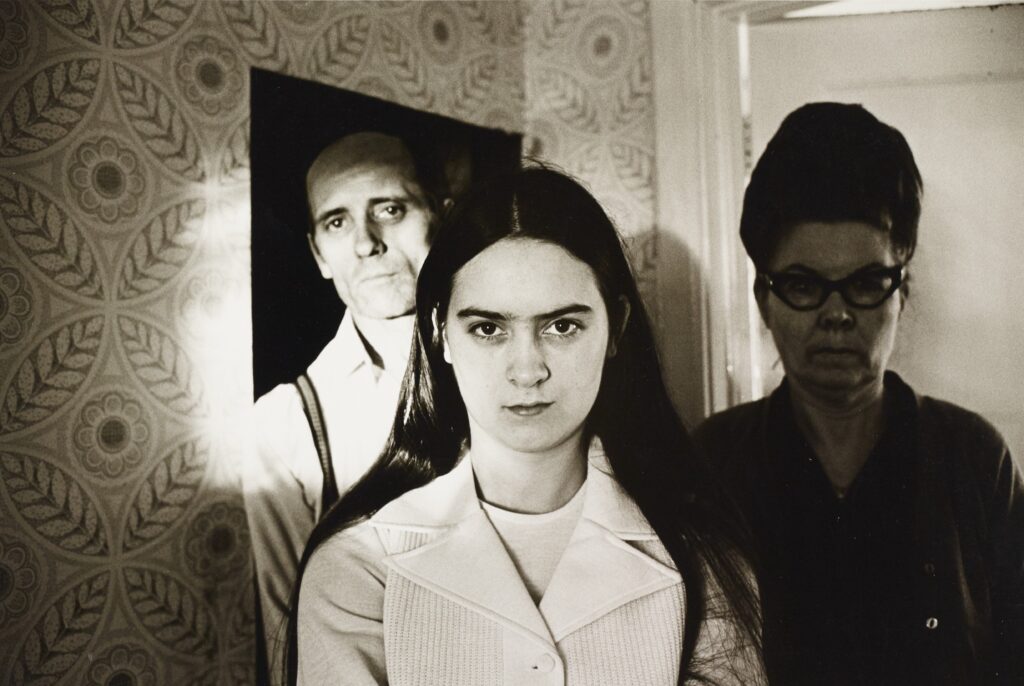

In contrast to the solidness of the objects, MacWeeney ultimately shows the social impact of the killing through depicting and immortalising people—from the British foot patrol roaming the streets of Derry, to a stop-and-search, where two Irishmen are stopped, put against a wall and patted down by British forces. Another haunting photograph shows a family peeking through their doorstep, surrounded by British military. Or, in one of the most famous and impactful photographs within the series, two women pictured after a British raid, disheveled, traumatised and tired. In this light, MacWeeney’s photographs have become an invaluable record of time, depicting historical facts and dynamics which show the conflict through the lens of the Irish people.

Left: Burnt out bus Belfast, 1971. Center: Two women after a house search, Belfast, 1971. Right: [British soldiers engaged in Stop and Search], 1971. Photographs above by Alen MacWeeney. Courtesy University College Cork © 2022 (All Rights Reserved).

Sinéad O’Connor and collective grief

In the words of late singer and activist Sinéad O’Connor, who, in her song Famine, made a great observation about collective grief and interpersonal trauma as she reflects on the effects that selective starvation had on the Irish people: “An American army regulation / says you mustn’t kill more than ten percent of a nation / ‘cause to do causes permanent psychological damage.” She is referring to the Irish population as suffering from collective “post-traumatic stress disorder”, which causes individual and social problems such as alcoholism, drug-addiction and ultimately, killing and murder (“massive self-destruction”). The pungent observations found within Famine can be backed up by current sociological research, in which studies on understanding how traumatic historical events, such as genocides and starvations, can impact an individual down to the genes, are being conducted. This shows how individual grief and health can be affected by large-scale historical events. Thus, MacWeeney’s photographs depict not only a time of historical change, but also a time of internal change, fragmentation and pain. O’Connor reiterates that in order to heal from such traumatic change individually and as a nation, remembering and grieving need to take place. It is apparent how O’Connor’s beliefs about the Famine can be extended and applied also to the Troubles as a time of collective social trauma.

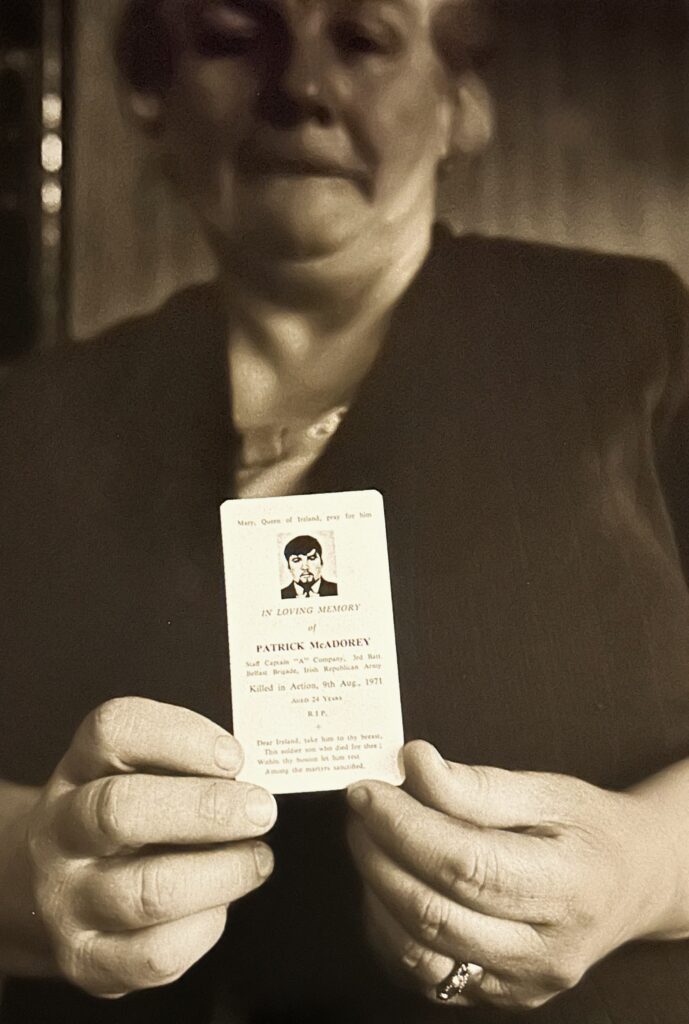

One picture within the series is perhaps particularly poignant and visceral: it is a close-up photograph of a funeral card, reading “In Loving Memory of Patrick McAdorey”, held up by an elderly woman dressed in black.

Photograph by Alen MacWeeney. Courtesy University College Cork © 2022 (All Rights Reserved).

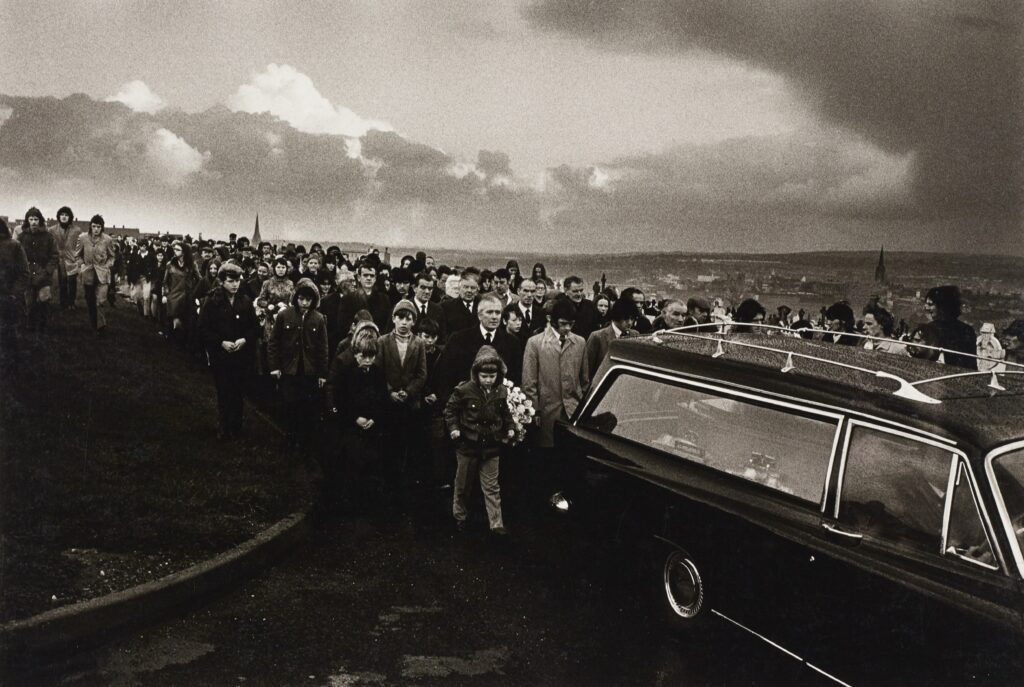

Within the Northern Ireland series, in fact, the personal and psychological hurt is apparent, as MacWeeney immortalises numerous funerals, funeral cards and portraits of grieving families. One picture within the series is perhaps particularly poignant and visceral: it is a close-up photograph of a funeral card, reading “In Loving Memory of Patrick McAdorey”, held up by an elderly woman dressed in black. McAdorey was only twenty-four years old at the time of his death. Another photograph shows a father holding up a picture of his dead son. The pain and hurt that transpire from his face is almost material, an object once again. The act of showing pictures of the victims of the conflict is to say to the viewer: “look at how young they were, how beautiful or ordinary. And yet, something happened. Somebody hurt them. And now I am here. They are not. But that is who they were.” It is a feeling of loss, of void, it is utterly personal. Beholden to the limitations of photography—capturing a fraction of a second at a time—MacWeeney only catches a glimpse of this moment in history, however, that is the true potential of the collection: its documentation serves as a visual way to remember, feel, hurt, and ultimately grieve, along with being a historical testimony.

Left: IRA Funeral, Londenderry, 1971. Right: IRA funeral, Londonderry [at the burial], 1971. Photographs above by Alen MacWeeney. Courtesy University College Cork © 2022 (All Rights Reserved).