How to preserve, cite, and design websites for the long-term future

- Deborah Thorpe

- June 8, 2023

The life and afterlife of webpages

by Deborah Thorpe, Research Data Steward, University College Cork Library

This is a three-part blog series, please click the link at the bottom of each post to proceed to the next

INTRODUCTION

I think it was kind of a cruel joke to call webpages pages because you would think of them as lasting a long time, you know, Gutenberg Bibles and all of that kind of thing, and nope. (Brewster Kahle, 2023)

What is the average lifespan of a website?

Back in 2003, Brewster Kahle of the Internet Archive put the figure at 100 days, quoted in The Washington Post. This figure has been cited persistently in other articles since, such as a 2015 article in The New Yorker. The exact figure seems to be debatable and/or possibly difficult to quantify due to the proliferation of web pages on the internet, but ‘there seems to be agreement that large portions of the web are very ephemeral’ (see The SAGE Handbook of Web History, p.16).

Web content may be changed, it may be moved to a different address or subdirectory on a website, or it may be deleted when it is left unmaintained and uncared-for. If actively maintained by website owners/administrators, users may be ‘redirected’ to moved content; however, in practice these redirects are often not put in place or not maintained for long. As well as being moved, old or out of date content is often removed (‘content rot’ or ‘404 – Page Not Found’), or simply updated with no way of viewing earlier versions (‘content drift’). One study, which inspired the creation of the service Perma.cc (more on that later), found more than 70% of the URLs cited in law journals from 1999-2011 did not link to the originally cited information.

Alternatively, content may be intentionally deleted for various reasons: in 2013 it was reported that the UK Conservative Party deleted a decade of political speeches from its website, including then-Prime Minister David Cameron’s speech praising the internet for making more information available. Computer Weekly‘s Mark Ballard told The Guardian that it, ‘shows how fragile the historic record is on the internet’. In 2017, we learned that the Donald Trump administration had ‘taken a hatchet to climate change language across government websites’. An entire section on climate change was ‘replaced by a perfunctory page entitled “An America first energy plan”’.

Websites developed by research projects often serve as a dissemination platform for interested stakeholders. Researchers use the website to share the objectives of a project; share the project progress as news and/or blogs; provide a calendar of events; host exhibitions; and/or link to interim and final deliverables such as publications. In many cases, notably humanities projects, an interactive web resource is the final deliverable for which the funding was given.

Once a project has ended, the web resource may remain available; the website might continue to direct visitors to your data and publications; and the website may serve as an important historical and cultural record. However, websites evolve over time and the purpose of that site is likely to not be the same after you have finished your project as it was during it. It may not be updated and maintained in the same way once funding and staffing have ended. Additionally, with the rise of cyber attacks, an unpatched server or a web application which isn’t regularly updated rapidly becomes a security risk and central university services are increasingly unwilling or unable to continue to serve unmaintained websites indefinitely.

The web, by its nature, ‘allows one to publish a work online and keep on updating it’ (my italics). When a user visits a website, they ‘want and expect good resources to be maintained. They expect the interface to be refreshed, corrections to be made, and content to be updated’. A defunct website; a website with errors or broken links; and/or a website that does not contain the content that the visitor is expecting is a big problem that becomes bigger as time passes. As an ephemeral platform by design, the web is not well suited for ‘the scholarly record’ without additional steps being taken by the creator, maintainer or a third part such as a web archive.

This blog post advocates for the necessity of planning for the end of and eventual retirement of online resources linked to a project as part of the process of devising the project itself; bearing in mind the technologies and services that have to be dealt with and can be utilised; what should be preserved and what cannot easily be preserved; and how web content should be cited in a way that is mindful of the fragility of content on the internet. A data management plan (DMP) and risk register cannot predict all potential pitfalls, but it can empower academics when the time comes to mitigate or prevent archiving-related disasters.

SERVICES

Lawyers love [the Wayback Machine] because they can use it to say, hey. You said this before, and now you’re not saying that. It’s the only record often. (Brewster Kahle, 2023)

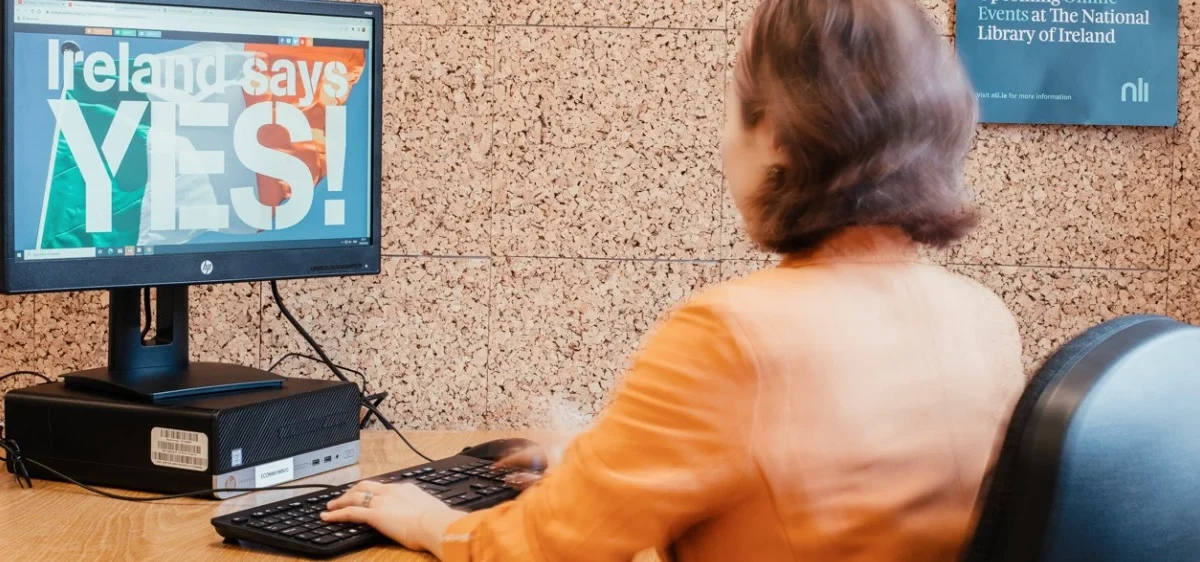

The National Library of Ireland’s Web Archive

The National Library of Ireland (NLI) is the library of record for Ireland. However, its collections extend beyond the photographs, manuscripts, maps and other physical material that you might associate with it due to its long history since its establishment in 1877. The NLI also has both digitised and born-digital content and also a growing collection of the archived Irish web. The NLI has been archiving Irish websites since 2007 working with a number of partners, including most recently the Internet Archive’s Archive-It service. As of 2022, there were over 2,300 sites in the Archive, many captured multiple times – and 44 TB raw data available in the NLI Selective Web Archive and preserved as part of the national collections of Ireland. Additionally, in 2007 and 2017, the NLI carried out broad preservation ‘domain crawls’ of the ‘.ie’ Country Code Top-level Domain (ccTLD), but these are not currently accessible for research or study.

The key word here is ‘Selective’. Certain content is captured using a ‘comprehensive’ approach, aiming to ‘capture an annual archive of government departments, higher education institutes and local authorities’. The NLI also broadens and diversifies this content by working with subject specialists and partners to select additional content. Website owners are notified of the NLI’s intention to archive, and there is a takedown policy. The NLI is awaiting legislative clarification before resuming more regular domain crawls. However, it should be noted that even annual crawling at a national level cannot capture all content on all websites and is therefore a complement to rather than a replacement of the selective, curated or event-driven approach.

Once selected, sites are collected by a ‘web crawler’, an automated piece of software designed to capture websites at a particular point in time, with the service currently being provided by Archive-it. The crawler scuttles into every corner of a website, clicking links and mapping out the contours of a page so that it can snapshot them. This ‘archiving phase’ takes upwards of 30 days and is then followed by quality assurance. In the final ‘access phase’, metadata is attached and is then made publicly available through the NLI’s portal. All websites that are archived by the NLI are preserved long term.

As an article written by staff of the NLI states, ‘efforts are also being made to work with communities to ensure wider representation in the web archive.’ The NLI Web Archive page includes a ‘Suggest A Website’ form. Proposers must specify if they are the owner/webmaster; their reason for nominating the site; and whether the website is at risk of deletion or substantial redevelopment. In terms of what will be selected for the archive, NLI’s Collection Development Policy guides collection development decisions, including those relating to the NLI Web Archive, and budgetary and other factors determine what can be archived each year.

The Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is a non-profit organisation that is building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form. One of its key services is the Wayback Machine, which makes over 26 years of web history accessible. Anyone who creates a free Internet Archive account can upload media (such as video, audio and images). Even without an account, users can capture a web page as it appears and it will be viewable for the long term using the Wayback Machine, as long as the Wayback Machine is available.

As an article in The New Yorker states, the webpages captured in the Wayback machine are the ‘dead web’ rather than the ‘live web’ and thus they do contain errors. For instance: ‘in October, 2012, if you asked the Wayback Machine to show you what cnn.com looked like on September 3, 2008, it would have shown you a page featuring stories about the 2008 McCain-Obama Presidential race, but the advertisement alongside it would have been for the 2012 Romney-Obama debate’. In addition, there are limits as to what the Internet Archive can collect in the first place: it does not, for instance, archive pages that require a password to access, or pages on secure servers. Furthermore, use of the Wayback machine is through URL search, requiring the person to know the URL of the resource that they want to find in the archive.

The Wayback machine’s ‘Save Page Now’ function, where the user enters a web address and that page is instantly added to its overall collection, is most suitable for individual users intending to capture a small number of pages. Organisations that are interested in archiving entire web sites or creating large collections of content would find the subscription service Archive-It more appropriate. A key difference for users is that archived websites available through Archive-It, such as those in the NLI Selective Web Archive, have full text searching whereas sites in the Wayback do not.