Beggars and Artisans: A Cultural History of Cork’s Franciscan Friary / Franciscan Friars in Cork: From Their Arrival to the Dissolution

- Elaine Harrington

- May 27, 2021

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

Beggars and Artisans: Franciscan Friars in Cork: From Their Arrival to the Dissolution

The early thirteenth century saw dramatic social, economic, religious and cultural changes in western Europe. The rise of cities and the increased wealth of merchant classes paradoxically led to the establishment of new religious orders known as the mendicants (or begging orders), who devoted themselves to absolute poverty. One of the main mendicant orders was the Order of St Francis, also called the Order of Friars Minor or the Franciscan Order.

The Franciscan Province of Ireland was established in 1230 during the general chapter of the Order held in Assisi, when the body of the Order’s founder, St Francis (1181/82-1226), was transitioned to the basilica dedicated to the Saint. It was at this chapter that Friar Richard of Ingworth, a pioneer member of the English Province, was elected as Ireland’s first minister provincial. After about nine years in Ireland, Richard went as a missionary to Syria, where he ‘died happily’, according to the Franciscan chronicler, Thomas of Eccleston (fl. 1232-59).

The earliest Franciscan friaries in Ireland were established in the eastern and south-eastern parts of the island; these areas had been dominated by the presence of the Anglo-Normans since the later twelfth century. Linguistic affiliation and reliance on alms for their day-to-day subsistence meant that the friars originally settled in the towns and boroughs of the Anglo-Norman colony, and their first houses were staffed mainly by English and Anglo-Irish friars. However, the Franciscans also benefitted from the support of Irish patrons and recruited across the two ethnic groups.

The origins of the Cork friary, its date and the names of the founders remain unclear. Canice Mooney, a great twentieth-century historian of the Franciscan Order, suggested in his contribution to Franciscan Cork: A Souvenir of St. Francis Church, Cork, that the founder was Dermot MacCarthy, King of Desmond (d. 1229), married to the Anglo-Norman Petronilla Bloet. More than likely, the creation of the friary was a long process that required multiple benefactors, and in fact, the various foundation dates (1229, 1230, 1231, 1240) and the various names of the founders (MacCarthy, de Barry, de Burgo, Prendergast) reflect the complexity of the process: from the initial arrival of the friars, their establishment in the area, the start of the friary’s building to the actual dedication of the friary.

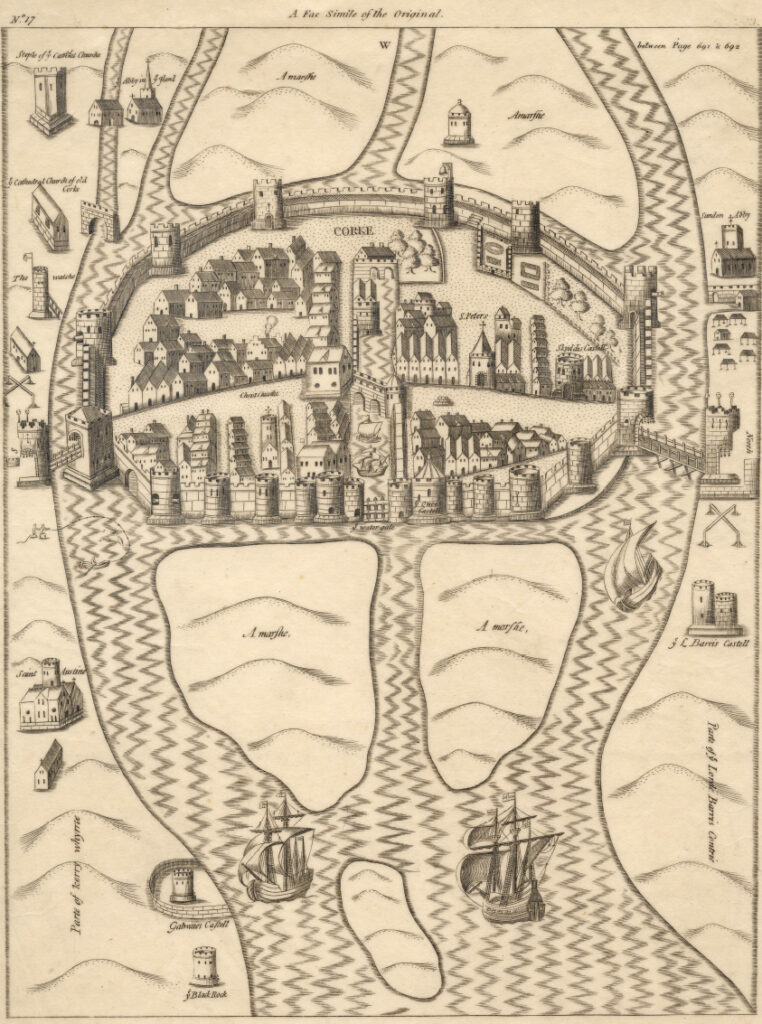

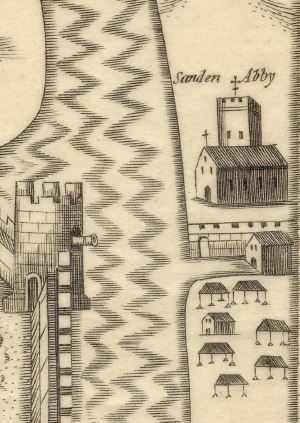

The MacCarthys continued to support the Franciscan Order in Munster throughout the Middle Ages. They patronised Timoleague friary, established in the thirteenth century, and in 1465 Cormac MacCarthy founded a Franciscan friary at Kilcrea, located opposite his castle. The location of Cork’s Franciscan friary in the area of Shandon just outside the city walls on the north side (see the next blog post) was a material manifestation of the friars’ preaching and pastoral care for the ethnically mixed communities of the townsfolk and the predominantly Irish inhabitants of the hinterland. As elsewhere, the friary acted as a stabiliser between the native Irish and the Anglo-Irish communities, however it was also a witness to racial tensions. The 1291 Franciscan provincial chapter held in Cork allegedly resulted in a physical confrontation between the native Irish and Anglo-Irish friars, and the killing of at least sixteen friars.

The liminal location of Cork’s Franciscan friary was balanced by the comparable position of the Dominican and Augustinian friaries, located outside the city walls on the south side. The friary benefited from the support of the royal exchequer, the nobility and the merchants. The will of a Cork’s merchant, John de Wynchedon, dated 1306, indicates his wealth and generosity for religious establishments, his own family and the city’s marginalized groups of the poor and the infirm, as well as the presence of intertwined social and religious networks in medieval Cork. John wished to be buried in the Augustinian friary, and his two sons were friars in the Dominican and Franciscan Orders respectively.

The medieval Cork friary held a prominent role in the Irish Franciscan Province as evidenced by a number of provincial chapters that met there and regular royal grants given for the purchase of friars’ habits. Cork friary also served as a studium or the place of studies. A late thirteenth-century Cork lector of English origin, whose name is unfortunately unknown, had trained in Paris and while in Ireland compiled a book of colourful stories (around 1275) that were used during sermons. One of the stories concerned a murdered widow from Carrigtwohill near Cork, who worked as a brewer and who, following her death, was eternally punished for leaving Mass too early.

From the fifteenth century, the Irish Franciscan friaries had been undergoing Observant reforms, which meant a return to a more austere lifestyle and the original ideals as envisaged by St Francis. Cork friars accepted the reform before 1518. A few decades later, in 1540, the friary was suppressed and a Cork merchant, called David Sheghan, received a lease of the friary’s weir, fishery and land; six tenants were allowed to rent the garden that had formerly belonged to the friary.

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the friars were scattered, some left the country and ended up in the Low Countries, Italy and Spain, some were imprisoned in Cork jail, while some continued their ministry from a place of refuge located in the city centre. Still, the memory of their original foundation in the Shandon area remained a powerful part of their identity as seen on liturgical objects commissioned by and for the Cork friars.

Photo: Małgorzata Krasnodębska-D’Aughton. ©UCD-OFM Partnership.

In spite of the friars’ dispersal and the destruction of their medieval friary, a number of chalices created in the early seventeenth century bear inscriptions that state how these precious objects were made for the Friars Minor of Shandon.

Małgorzata Krasnodębska-D’Aughton

Further reading

Fitzmaurice, E. B. and A. G. Little, ed., Materials for the History of the Franciscan Province of Ireland, 1230-1450 (Manchester, 1920)

Jones, David, Friars’ Tales: Thirteenth-century Exempla from the British Isles (Manchester, 2011).

Krasnodębska-D’Aughton, Małgorzata, ‘Me Fieri Fecit: Franciscan Chalices 1600-1650’ and ‘Catalogue’, in R. Ó Floinn, ed., Franciscan Faith: Sacred Art in Ireland, AD 1600-1750 (Dublin, 2011), 71-183.

Lafaye, Anne-Julie, ‘Reconstructing the Landscape of the Mendicants in East Munster: The Franciscans’, on Academia, accessed 25.05.2021.

McDermott, Yvonne, ‘Returning to Core Principles’, History Ireland 15/1 (2007), 12-17.

Mooney, Canice, ‘The Mirror of All Ireland. The Story of the Franciscan Friary of Cork, 1229-1900’, in Jerome O’Callaghan, ed., Franciscan Cork: A Souvenir of St. Francis Church (Killiney, 1953).

O’Sullivan, D., ‘The Testament of John de Wynchedon of Cork, Anno 1306’, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 61 (1956), 75-88.

Thomas of Eccleston, The Friars and How They Came to England; Being a Translation of Thomas of Eccleston’s “De adventu F.F. minorum in Angliam”, Done into English with an Introductory Essay on the Spirit and Genius of the Franciscan Friars, by Father Cuthbert (London, 2015, originally published in London, 1903).