Mapping Cork: Trade, Culture and Politics in Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland / Fashion and Rags

- Elaine Harrington

- May 19, 2020

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

Mapping Cork: Fashion and Rags

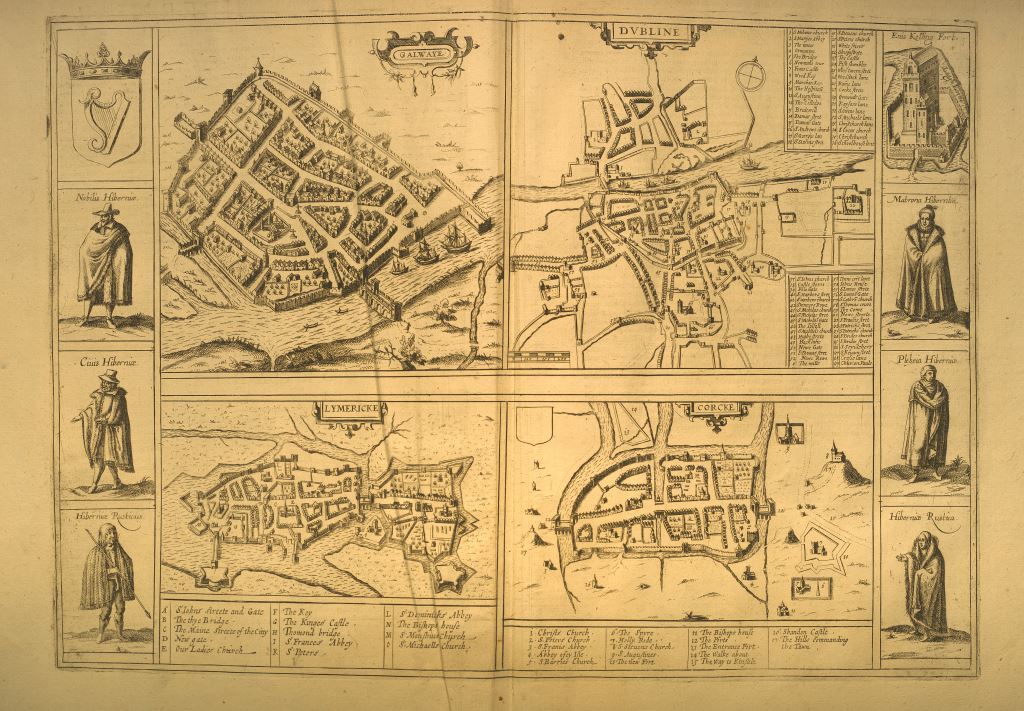

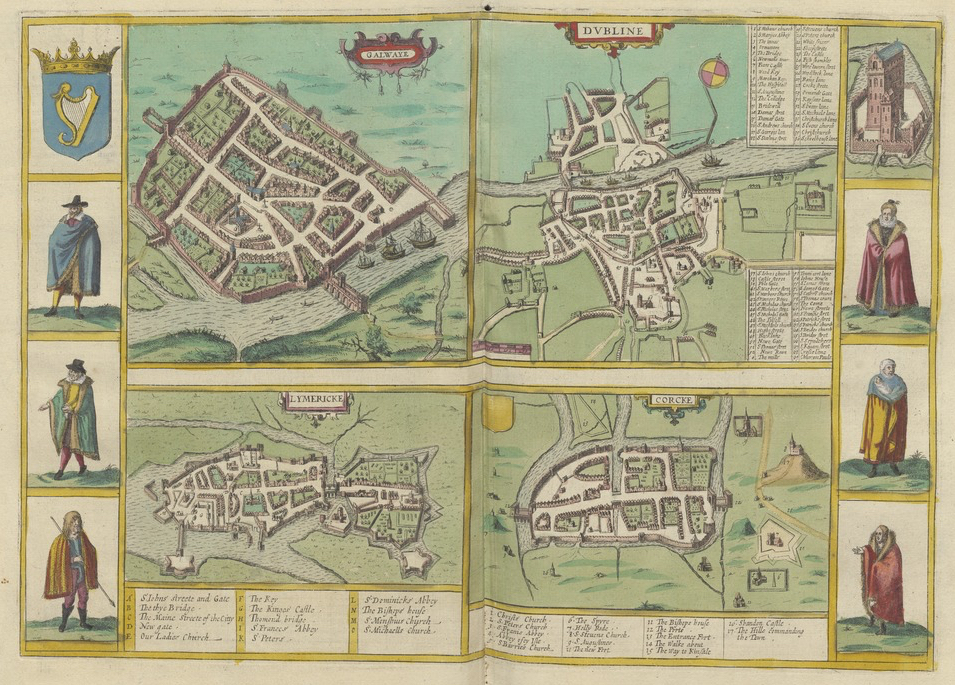

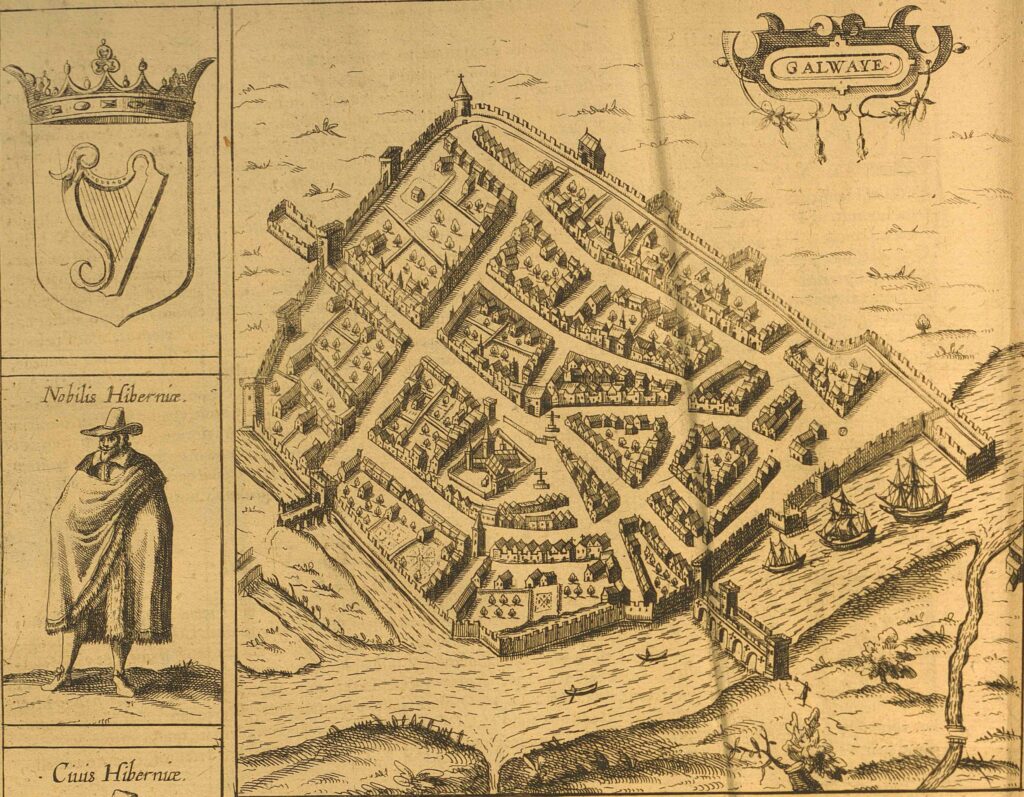

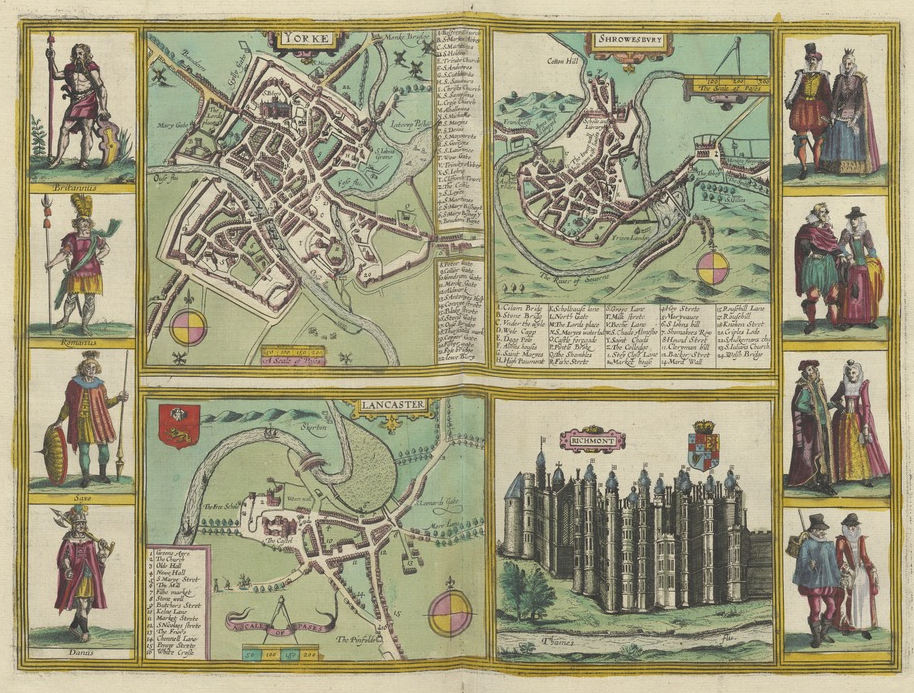

The Civitates Orbis Terrarum was a carefully thought-out tool to inform the reader about the chief cities of the known world, where individual pages were constructed from existing maps and costume books. Each detail contained cultural references that would have been understood by the early modern viewer. On the Irish page the maps of the four cities (Dublin, Galway, Limerick and Cork) are flanked by six figures representing Irish society. The order of the figures suggests a scale of affluence, the very richest are depicted on the top and the poorest at the bottom of the page.

The top pair includes an Irish nobleman on the left and an Irish matron on the right. Their clothes demonstrate what the fabulously rich and well adorned people wore, with the man sporting a splayed collar and a pointed hat, and the woman wearing a ruff and opulent fur-lined coat, which was the fashion of the time among the wealthy.

The middle pair consists of Irish town-folk, with a man on the left and a woman on the right, wearing more modest but very respectable attire.

The bottom pair on the page shows the rural Irish, once again placing the man on the left and the woman on the right. In direct contrast to the Irish nobility, the rural Irish wear functional clothing, including mantles.

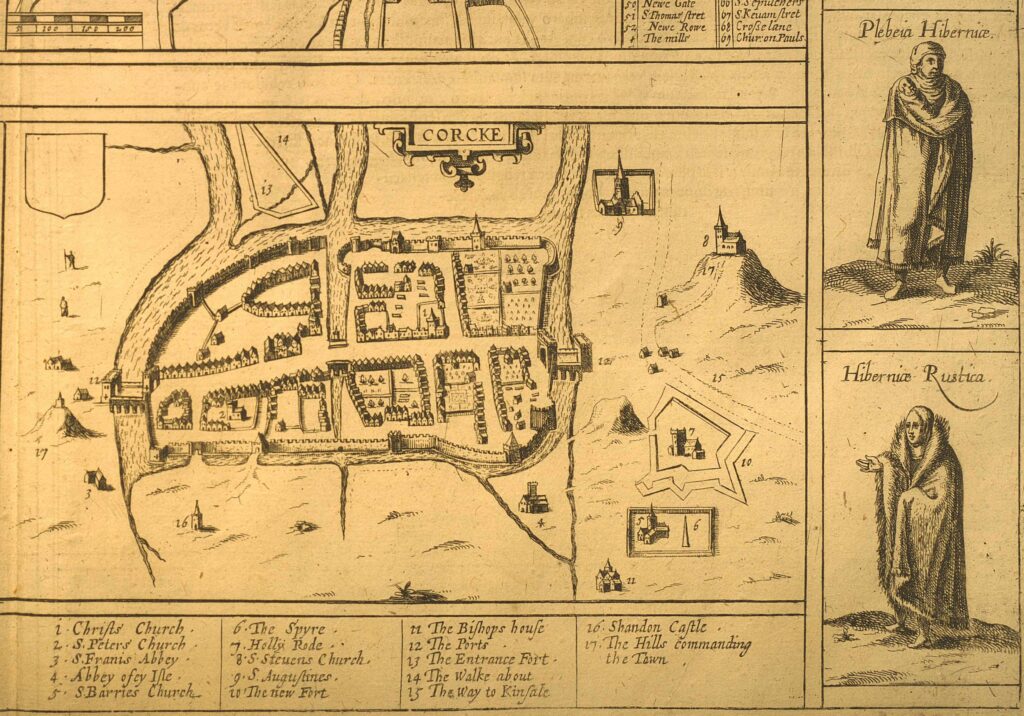

It is perhaps little coincidence that the poorest Irish people flank the cities that the map seems to represent as the least busy and rich. In comparison to the bustling city of Galway, with its dozens of buildings, impressive walls and a busy waterway, Cork may appear to be shown as sparse and lacklustre. There are fewer buildings and no ships sailing in its waters, which may suggest to the viewer a lack of trade and commerce, and little in the way of cultural vibrancy in Cork city. But as can be seen from other blog posts in this online exhibition, Cork acted as an important trade centre in the medieval and early modern periods.

For the rural Irish to be placed alongside the map of Cork was a means of conveying to the viewer the nature of Cork and its hinterland as uncivilised or at least simple and rather backward. The map reinforces this image through the use of the words ‘rusticus’ and ‘rustica’, Latin words for ‘a country-dweller’, to describe the Irish man and woman who are placed in the lower level of the page that also includes the map of Cork at the same lower level. While the word ‘rusticus’ can evoke uncivilised qualities of country-dwellers, it can also refer to their simplicity. Saint Patrick, for example, described himself as ‘the most simple country person’ or ‘rusticissimus’.

In the Civitates, the page with four maps of Irish cities is accompanied by a brief description of each city: Cork is described as not very big, yet densely populated and prosperous, with the surrounding area inhabited by seditious people. This description of the city, labels ‘rusticus’ and ‘rustica’ and the inclusion of the Irish mantles, would evoke to the viewer’s mind the cultural stereotype of the Irish as savage and uncivilised, more at home amongst the wilds. Such views of the indigenous Irish have their origins in the classical world with some writers describing the Irish as violent, incestuous and cannibalistic. In contrast the English rural dwellers, seen on the Civitates page with the images of the English cities, are presented wearing more elaborate clothing.

Following the late twelfth-century Anglo-Norman invasion, ideas of Irish barbarism became fully entrenched within the European mindset. The cleric Gerald of Wales (c. 1146 – c. 1223) drew upon ancient ideas of Irish barbarity in his widely copied books The Topography of Ireland and The Conquest of Ireland. Gerald’s texts, written in Latin, were the seminal points of reference for hostile early modern English views concerning the Irish people.

The depiction of Cork as a walled city, which needed multiple fortifications in its suburbs, suggested to the viewer the potential threat from the Gaelic Irish. The surrounding lands of Cork are bereft of roads and have scattered built structures in the countryside. Consequently, Cork’s hinterland appears dangerous and the city with its walls suggests potential threats from the uncivilised Irish. The English readership would identify any civilisation in Cork as a direct result of the Anglo-Norman conquest. The map and accompanying images revealed to the European mindset the dual nature of Cork as influenced by the medieval ideas of civility and barbarity. At the time of the map’s creation, the early modern Gaelic Irish were still viewed as wild and savage, akin to their medieval ancestors, as seen in the artwork of the famous German painter and craftsman Albrecht Dürer and the Flemish artist Lucas d’Heere.

Andrew Neville

Further reading

Ainsworth, Peter F., Jean Froissart and the Fabric of History: Truth, Myth and Fiction in the Chroniques (Oxford, 1990).

Davies, R.R., The First English Empire (Oxford, 2003).

Downham, Clare, Medieval Ireland (Cambridge, 2011).

Friedman, John Block, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge, MA, 1981).

McGettigan, Darren, Richard II and the Irish Kings (Dublin, 2016).

Morgan, Hiram, ‘Albrecht Dürer: First Superstar of Northern European Art’, History Ireland 14 (2006), online edition.