Mapping Cork: Trade, Culture and Politics in Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland / Representing Ireland in Maps Before the Civitates Orbis Terrarum

- Elaine Harrington

- May 18, 2020

Student Exhibition, MA in Medieval History

Mapping Cork: Representing Ireland in Maps before the Civitates Orbis Terrarum: Ortelius and English Colonial Perspectives

The pioneering cartographer Abraham Ortelius asserted: ‘Historiae oculus geographia’ (meaning that ‘geography is the eye of history’). His Theatrum Orbis Terrarum or Theatre of the World was the first modern atlas. It was initially published in Antwerp in 1570, and continuously revised and extended until 1612. It was immensely successful and influential.

Ortelius included a map of Ireland in his 1573 edition of the Theatrum. Originating in an erudite Anglo-Flemish milieu, the map is oriented west-east and presents Ireland as ‘a British island’ partially under English control. Cities and towns are dotted along the island’s eastern and southern coasts, where English rule was strongest. Great wildernesses, mountains, woods, rivers and lakes cover much of the rest of Ireland, particularly Ulster and Connacht, where the indigenous Gaelic Irish were dominant.

The map also contains texts credited to Gerald of Wales’s late twelfth-century Topographia Hibernica or Topography of Ireland (1188). Gerald had revived and extended Graeco-Roman ethnic stereotypes of the Irish as exotic, barbarous and sexually deviant. The Geraldine texts incorporated in Ortelius’s map also emphasise that the Irish live on a remote oceanic island of marvels. These include Lough Erne, where the spires of churches may be seen beneath its waves: evidence that God had flooded the region because of its inhabitants’ bestiality.

The Theatrum was very well received by the English colonial elite in Ireland, whose views had helped to shape its representation of the country and its inhabitants. Because of the map’s inclusion in the Theatrum, their interpretation of Irish geography, history, culture and society now circulated in print among Europe’s intelligentsia and ruling classes.

Gerald presents the conquest under King Henry II of England as a civilising mission. The Irish are a ‘gens silvestris’ (‘a woodland people’): intelligent, handsome and untamed barbarians who spurn cultural progress for idle pastoralism in an uncultivated wilderness. The Topographia states that in contrast to the ‘literally barbarous’ Irish, ‘man usually progresses from woods to fields, and from fields to settlements and communities of citizens’.

This idea of human progress was inherited from ancient Greece and Rome. Gerald’s Latin conveys subtleties lost in English. A citizen (civis) lives in an association of citizens or civitas, giving us the word ‘city’. This settled, communal and interdependent way of life leads to civilitas: civility or civilisation. Gerald’s insistence on the literal barbarism of the Irish recalls Cassiodorus’s theory that the Latin word for a barbarian (‘barbarus’) comes from ‘barba’ (‘beard’) and ‘rus’ (‘countryside’). This matches Gerald’s description of the unkempt ‘flowing hair and beards’ of the wild, forest-dwelling Irish.

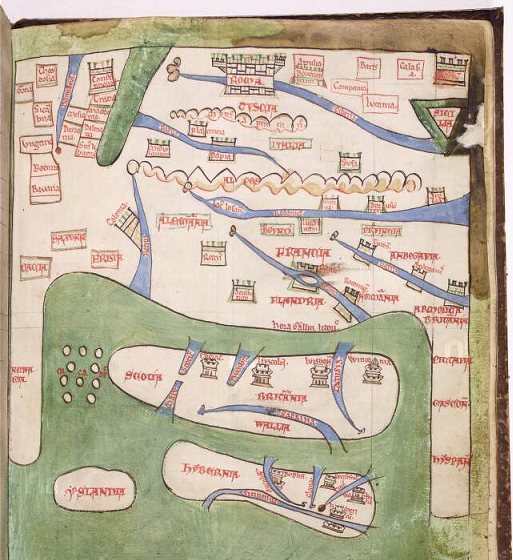

A map of Europe, oriented east-west, accompanies Gerald’s Irish narratives in a manuscript (c. 1200) owned by the National Library of Ireland. It emphasises Ireland’s remoteness at the western ends of the earth (Gerald argued that isolation from the wider world caused Irish primitivism).

The map’s depiction of cities in Ireland visually reinforces the texts’ emphasis on Irish rejection of urban life. The Topographic and Expugnatio make it clear that the cities shown on the map – Dublin, Wexford, Waterford and Limerick – were Viking foundations, surrounded ‘with fine trenches and walls’ against the Gaelic Irish. The ‘innate laziness’ of the Irish meant that they allowed the Vikings to build these cities for trading purposes; the Irish themselves ‘did not bother to sail the seas or have much truck with commerce’.

Two cities shown in the Civitates are absent from this map: Galway and Cork. The Anglo-Normans had not yet conquered Connacht and founded Galway. The omission of Cork may be deliberate, since Gerald knew that its origins were Gaelic Irish: ‘the land of St Finbarr’.

Gerald and other sources indicate that the Anglo-Normans seized Cork in the 1170s. In Ortelius’s time, it was a resolutely English city in its cultural affiliations and political loyalties. Ortelius’s map of Ireland shows Cork as an island in the river Lee, its urban status symbolised by an image of buildings surmounted by a cross. Westwards, the map displays ‘the grene wode’, mountains and open country.

The Civitates Orbis Terrarum: The City and Civilisation

Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarum gave Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg a model for the title and conceptual framework of their Civitates Orbis Terrarum or Cities of the World. This work was first published in Cologne and Antwerp, and appeared in six volumes between 1572 and 1617. Its maps, plans, profiles and bird’s eye views of cities and landscapes were mostly copied from existing publications, and its texts were written in Latin, though versions in French and German also appeared.

The Civitates provides an urban companion to the Theatrum’s survey of global geography. Both enterprises are interested in far more than the delineation of physical and political space. They are concerned with identity, culture, and society, manifested in appearance, clothing and behaviour, institutions, laws, customs, traditions, beliefs and myths, and the resources and wonders of the natural world that make the human experience possible and pleasurable. For Ortelius, and Braun and Hogenberg, geography is indeed the eye of history, understood as the study of human life in its multifarious aspects and contexts.

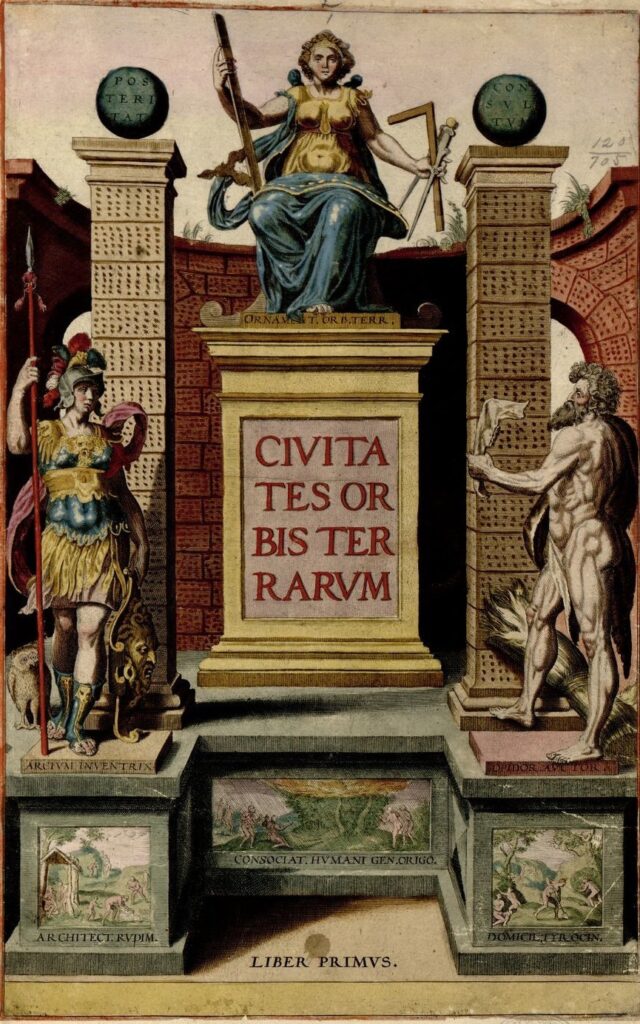

The idea of the city as the zenith of human achievement is central to the Civitates and Theatrum. The title page of the Civitates gives visual expression to this idea.

It is dominated by an image of the Graeco-Roman Magna Mater or Great Mother deity, holding instruments vital for the design and construction of buildings. Accompanying texts and images indicate that humanity came together and progressed from barbarous isolation to civilised urban association via the discovery of fire, and the development of settled agriculture and the rudiments of architecture.

But the title page of the Civitates also cites classical and biblical myths linking cities and civilisation with violence. Athena, the patron goddess of wisdom, crafts and war, is described as the inventor of the citadel. Cain, the first murderer and builder of the first city (Genesis 4:17), is referenced as the founder of towns.

The Civitates Orbis Terrarum in Geo-Political Context

The Civitates appeared in an age of high civilisation and bitter wars. Most of its maps feature European cities in lands ranging eastwards from Ireland to Russia. Its city maps of Africa, Asia and the Americas tend to feature centres of spiritual, cultural, political, strategic and mercantile interest to Europeans. Jerusalem, for example, is shown in three separate maps, indicating its exceptional importance in the European Christian thought-world.

Later sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Europe was fractured by secular struggles for power and territory, merging with confessional struggles arising from the Reformation. The splintering of the Western Church into Catholic and Protestant denominations added to existing divisions between the West and Eastern Orthodoxy. The Civitates reflects these tensions, but nevertheless posits a common European religious and cultural heritage that faces an existential outside threat. Braun identifies the Ottoman Turkish empire as the mortal enemy of a Europe coterminous with Christendom. Writing only a year after the decisive battle of Lepanto (1571), when the Holy League routed the Ottoman fleet in the Mediterranean, he claims that Islamic prohibitions on the use of images means that the Turks cannot use the Civitates’s detailed urban maps and plans in their wars since they include representations of human beings.

Contexts for the Representation of Ireland in the Civitates Orbis Terrarum

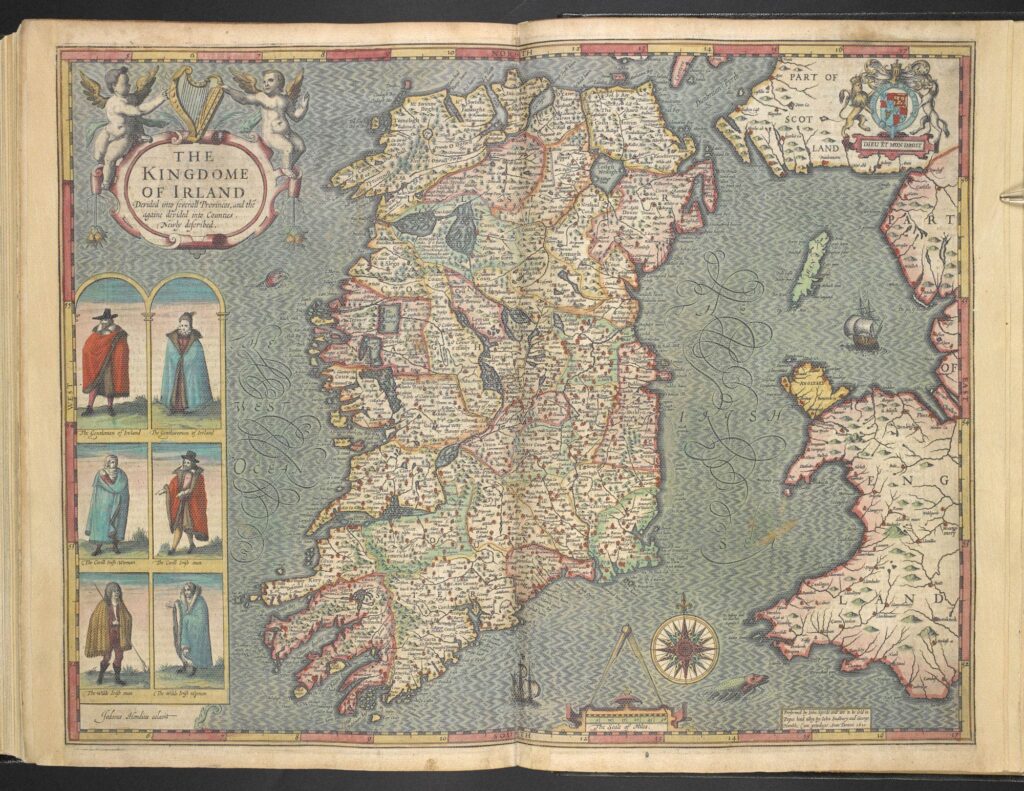

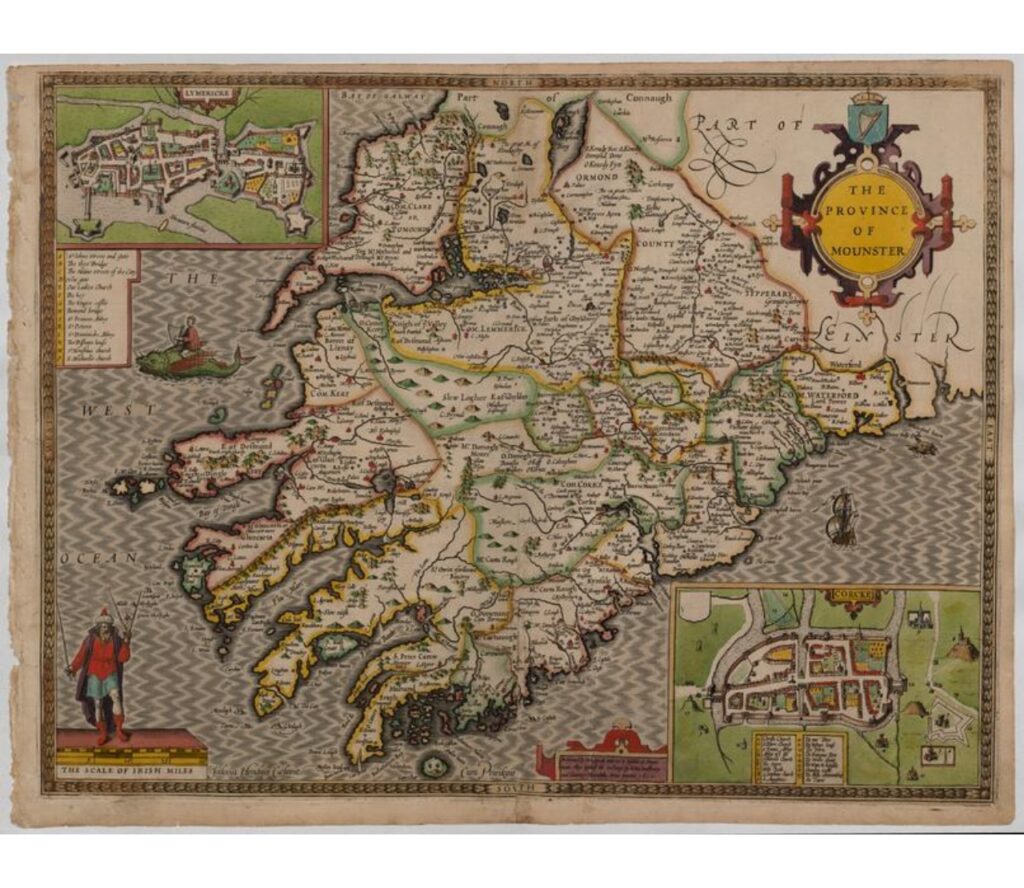

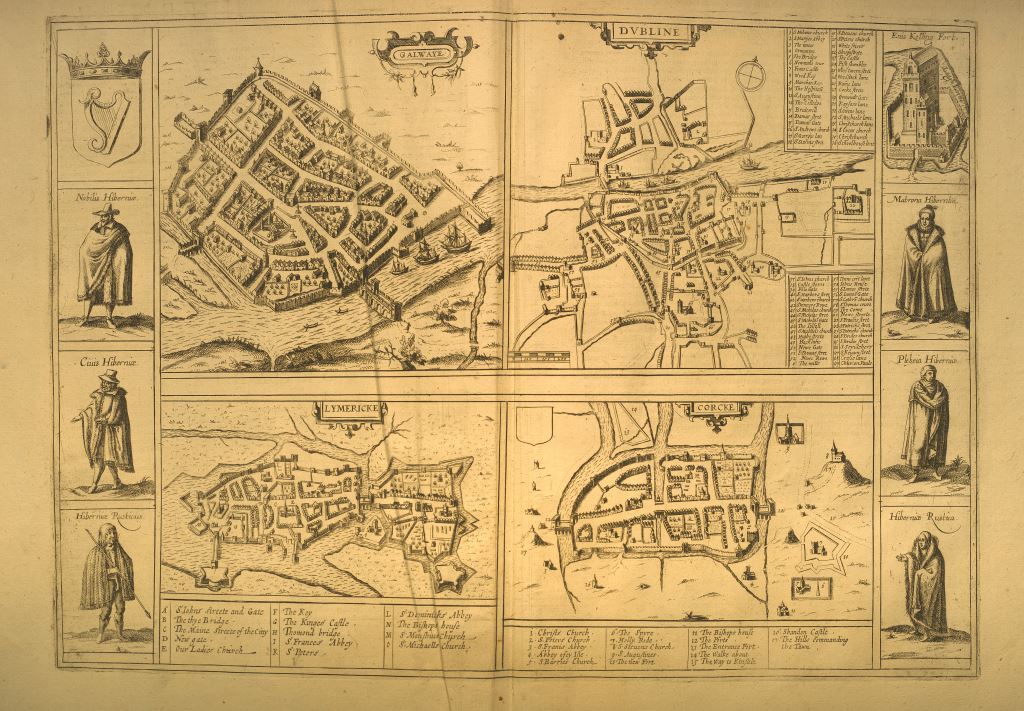

The Civitates map of Cork and the cities of Dublin, Galway and Limerick, and its representation of different social groups in Ireland, also reflects contemporary conflicts, and related ethnic and cultural stereotyping. The materials concerning Ireland appear in the atlas’s sixth and final volume, and offer an imperial English vision of the island within a British context. The extended title of the Civitates’s source, and its allusion to Ortelius, is instructive: The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, Presenting an Exact geography of the Kingdomes of England, Scotland, Ireland and the Iles Adionying.

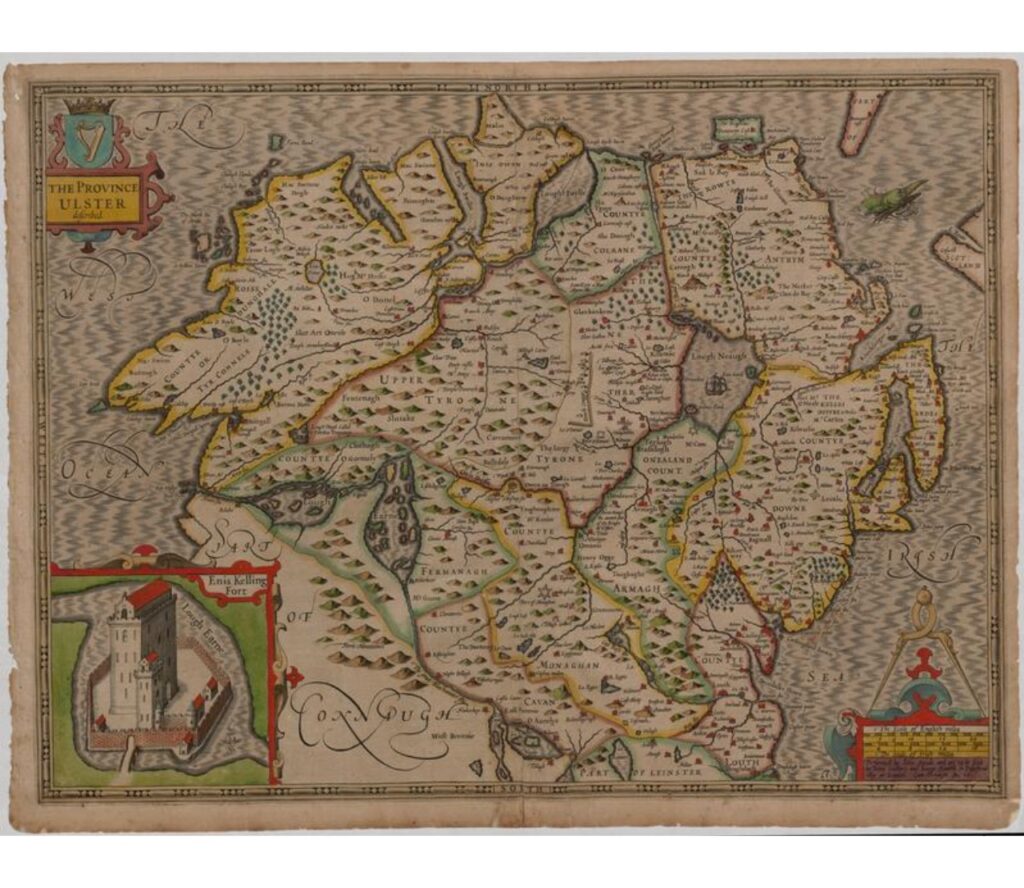

When the cartographer John Speed produced this atlas (1611-12), the English Crown had achieved hegemony over the entire archipelago. Speed dedicated his work to James I and VI of England and Scotland, ruling as ‘an Imperiall Maiestie’ with the new title of ‘King of Great Britaine’. James I and VI was also King of Ireland. In 1541, Ireland had been declared a kingdom under Henry VIII, who began to reassert English control over the island.

The Irish wars of the late Elizabethan period saw the Crown overwhelm Gaelic Ireland with unremitting violence, atrocity and famine. The poet Edmund Spenser, settling on confiscated lands in North Cork, supported this policy of terror and devastation, and described its impact on the people of Munster in his View of the Present State of Ireland (1596): ‘they looked like anatomies of death, they spake like ghosts crying out of their graves … in the shorte space there were almost none left, and a most populous and plentifull country suddanly made voyde of man or beast.’

The Harp and the Fort

Visually, Ireland appears to feature in the Civitates as an integral part of mainstream European civilisation: a Christian kingdom with cities and an agricultural base, under English rule but with distinctive regional variations from England in terms of clothing and personal grooming, particularly in the case of its country people.

If anything, the country looks even more soberly normative than the Ireland of Speed’s Theatre. Speed’s map of Cork city is embedded in his map of the province of Munster. Omitting Munster, the Civitates loses the sea-monster glimpsed off the Waterford coast and the boy-harpist riding another great monster in the ocean beyond Kerry.

But indications of violence and Irish otherness emerge from deeper engagement with the Civitates’s images and texts, and the cultural stereotypes that they contain. To conclude with a single example: consider the forbidding image in the upper-right panel next to the map of Dublin (below). It is directly opposite the crowned harp depicted in the upper-left panel next to Galway: a symbol of Ireland under the English Crown.

The upper-right panel displays ‘Enis Kelling Fort’: a tall, moated and fortified structure in ‘Lough Earne’. This image is taken from the Theatre’s map of Ulster, which Speed presents as mountainous, wooded and scarcely urbanised, and – no coincidence – the last stronghold of Gaelic Irish resistance to English rule. The English had captured Enniskillen Fort in 1594: a significant achievement in their advance across Ulster and one that enabled them more easily to defend their gains and suppress further resistance in the surrounding lands.

Enniskillen Fort’s inclusion in the Civitates, and its alignment with the crowned harp, indicates how English power over Ireland was achieved and maintained. The walls and fortifications of Dublin, Galway, Limerick and Cork, seen in the maps of those cities, were built with good reason.

Diarmuid Scully