This Reading Life: Fergal Gaynor

For each of the seven days of National Library Week 2015 the River-side blog will host responses from a group of seven contributors who were asked to nominate seven ‘formative’ books. The project is curated by Fergal Gaynor, who is also today’s contributor.

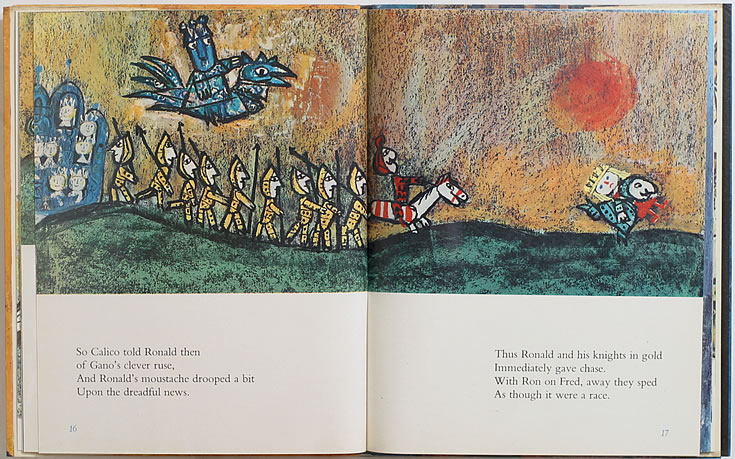

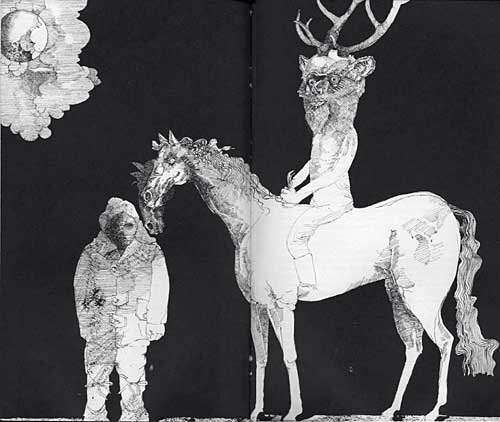

- Emanuele Luzzati: Ronald and the Wizard Calico (Armada Picture Lion, 1973)

Knights, wizards, great folk-modernist illustrations – what more could a young boy ask for? It must have been published – in translation? – very shortly before it was bought by my parents (at a book-fair held somewhere on the Mardyke? – I have a very vague memory of something of the sort).

Luzzati, I’ve just learned (from Wikipedia), was nominated for two Academy awards for his short films, and was an in-demand production designer for operas. He was Italian, but as a Jew decided to relocate to Switzerland in 1938. Strange to put that fact and the world of Ronald and his Golden Knights together.

- J M Cohen: Poetry of this Age (Grey Arrow, 1966)

Already mentioned on Day 2 by Trevor, this paperback of my father’s was more or less my introduction to modern poetry. Eliot, Yeats, Hopkins, Dylan Thomas, Thomas Kinsella and a few others I knew thanks to Soundings, Gus Martin’s Leaving Cert English course-book. And I’d come across Lorca and Rimbaud from dips into my Dad’s Penguin collections of national verse – but Cohen gave me a full spectrum.

The extracts from Mayakovsky and Rilke impressed me most, and I serendipitously came upon a Picador selected Rilke, with translations by Stephen Mitchell, in a Porter’s newsagents in Wilton Shopping Centre soon after (where I was also to buy Brave New World). Cohen’s ‘this age’ ended in 1965, and I was reading around 1985 – explains a lot.

- Carl E Schorske: Fin-de-Siècle Vienna (Vintage Books, 1981)

This entry was supposed to be about Beckett (yes, him again) – about the thin Faber editions of short plays like Rockaby that appeared in the late seventies and early eighties. I bought them, chiefly, because they were affordable for a teenager – and if you didn’t get too many words for your punt, every word you got was potent. They provided a real education in language. I would have mentioned, as well, that when I later spent a couple of years working in Waterstone’s I was shocked to realise that among the salesmen who periodically hovered at the cash-desk, usually suited, tired-looking and with anxious smiles, representatives of giant distribution companies, the one, well-spoken individual who stood out – short, older, and wrapped in woollen scarf and long-coat – was John Calder, still hawking his friend Beckett’s wares from shop to shop.

But then I heard that Carl Schorske had died – at the fine age of one hundred. So this is dedicated to him, and an intellectual and cultural history of Vienna at its neurotic height, that gave me great pleasure. And even inspired a poem.

- Anthony Blunt: Art and Architecture in France 1500-1700 (Yale UP / Pelican History of Art, 1999)

I have to include an art book in my list. My Gombrich’s Story of Art, that my Dad borrowed from the library here in 1978 and never returned (ahem – this is a bit of a running theme in these posts), and which I read perched in a leylandii in my grandparents’ garden some summer in the mid-eighties, is a candidate. The massive, illustration-rich books from the same university library that I read as an undergraduate (you could borrow them, which was like bringing a gallery home) – Edward Quinn’s book on Max Ernst being representative – have to be mentioned.

But I’ll go for Anthony Blunt’s classic, originally published in 1953, which I read during some hard months in 2006. The images of the early classical buildings – by the likes of François Mansart and Philibert De l’Orme – described with a careful clarity by the unfortunately named (and shadowy) Blunt – were something that could be held onto while other things slipped away.

- D. H. Lawrence: Complete Poems (Penguin, 1994)

I spent the best part of seven years working on a PhD, and such a span of intense reading (and much niggly textual processing, which is quite a different matter, pace ‘information literacy’) is bound to leave a mark. For my sins, I made the miner’s son from Nottinghamshire, D. H. Lawrence, the focus of my thesis. It was a time when the tide of his popularity was well below the high watermark of the sixties and early seventies (it hasn’t risen too much since).

My relation to his writing was odd enough – I would open something, not really in a state of eager anticipation, and within a few sentences find myself with a very distinct, familiar voice. What followed was like an altercation or protracted argument – it was certainly nothing like pleasurable consumption (Lawrencean pun not intended). I usually found, however, within a paragraph or two, that I’d missed these vivid, staged disagreements, and the opening of that otherwise absent, and brightly coloured world. Even at his most rhapsodic he was something of a gadfly, and even at his most irritating he could offer marvellous, ‘quick’ (a Lawrencean word) observation.

I became interested in his work through his spat with psychoanalysis, Fantasia of the Unconscious (noticed in Waterstone’s because of its Roland Penrose cover), and found myself most often in the orbit of that attempted epic The Rainbow – a hyperbolic Middlemarch drawing a narrative from Genesis, through Victorian life and thought, to a twentieth century of new, molten men and women seeking individual form (no less).

No. 6 on my list, however, has to be the fat Penguin ‘Complete Poems’, and the section dedicated to Birds, Beasts and Flowers (1923). ‘Snake’ is one of the first poems I remember my mother reading to me (along with Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind’) – though written in Sicily it managed to correspond to her memories of animals in Zambia (where she taught biology at a mission school in the mid-sixties). ‘Fish’ is my favourite – a masterpiece that somehow joins poetry and philosophy in a way reminiscent of those first questioners of the universe collected in Jonathan Barnes’ ‘Early Greek Philosophy’. And it has a fresh, modern idiom, whose visual appearance rehearses the turns, pauses and dashes of the unfolding poem. And I fish myself.

I have waited with a long rod

And suddenly pulled a gold-and-greenish, lucent fish from

below,

And had him fly like a halo round my head,

Lunging in the air on the line.

Unhooked his gorping, water-horny mouth.

And seen his horror-tilted eye,

His red-gold, water-precious, mirror-flat bright eye;

And felt him beat in my hand, with his mucous, leaping

life-throb.

And my heart accused itself

Thinking: I am not the measure of creation.

This is beyond me, this fish.

His God stands outside my God.

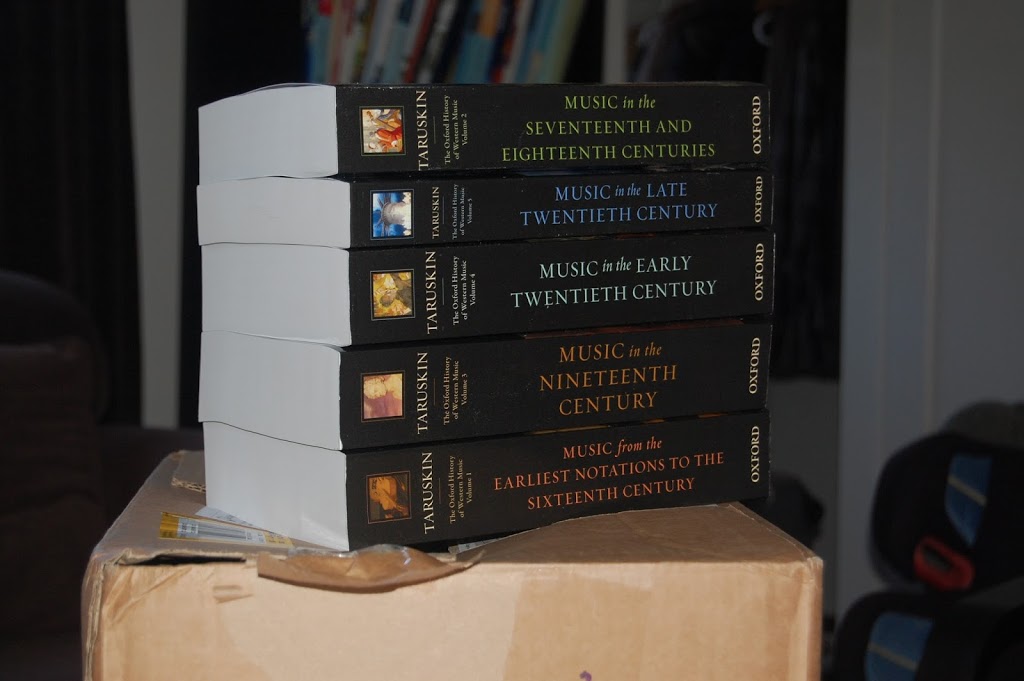

- Richard Taruskin: History of Western Music (Oxford UP, 2009)

My wife and I received the irascible Taruskin’s five-volume History of Western Music as a wedding present (now what kind of person would give a wedding present like that?). With a very limited ability to read music, and rudimentary knowledge of harmony, it’s been a struggle, but a highly rewarding one. Among other things it introduced the word ‘bobo’ (‘bourgeois bohemian’ – the patrons of US Minimalist opera in the seventies and eighties) into my vocabulary. And now I know what a ‘tone cluster’ is. But he’s not fair on Sibelius.

- Susan Cooper: The Dark is Rising (Atheneum, 1973)

So – Paul’s nabbed Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism already. I could plump for Between Past and Future or The Human Condition (‘The trouble with the modern theories of behaviorism is not that they are wrong but that they could become true.’), but I’ll leave Arendt with the single nomination. Philosophy-wise, E.M. Bernstein’s The Philosophy of the Novel: Lúkacs, Marxism and the Dialectics of Form (phew) was the unlikely starting point. It soon became all Germanic: Basic Writings: Martin Heidegger, Gadamer’s Truth and Method, Hollingdale’s Nietzsche Reader – a mind-assaulting Christmas present. Less loftily, I was one of those rural romantic sorts who went down the Tolkien rather than the science fiction path . . . Enid Starkie’s biography of my favourite poet, Arthur Rimbaud, stopped me writing for a decade . . .

However, I’m going to go back to primary school, and a book read by bands of streetlight in the back of a Fiat 124 parked outside the Uneeda Bookshop on Oliver Plunkett Street. It was an autumn evening, with shadowy shoppers passing the windows, and I was submerged in Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising, borrowed from Cork City Library. It was one of those off-shoots of a seventies Anglo-Welsh teenage culture of future-ancient weirdness that also produced Alan Garner’s novels and the HTV series Children of the Stones. If you’ve ever been a child walking a country road under an old, high estate wall – overshadowed by leafless elms and beeches – and a rook has taken to watching and following you – and you’ve wondered if there’s more than normal animal curiosity involved – then maybe it has something to do with the local barrow-graves and their ability, like Cooper’s book, to slip you into shadowy otherworlds . . .