This Reading Life: Raymond Deane

For each of the seven days of National Library Week 2015 the River-side blog will host responses from a group of seven contributors who were asked to nominate seven ‘formative’ books. The project is curated by Fergal Gaynor. Today’s contributor is composer Raymond Deane.

- Fritz Halbach: Schnuppeldiwupp (Verlag Perthes, Gotha 1922)

The first book that has stuck in my visual memory is Schnuppeldiwupp, a German children’s book from which my father occasionally read to my sister and myself at bedtime. This is what I wrote in my memoir, In My Own Light:

‘Another tale, German this time, was delightfully entitled Schnuppeldiwupp, by one Fritz Halbach. Its full title is Schnuppeldiwup: Eine Geschichte für Kinderherzen. “A story for childish hearts” sounds very appealing, yet I can remember nothing about it. Perhaps this lack of distinguishing features explains why neither book nor author has stood the test of time – or perhaps it is the Kinderherzen that have vanished.’

- Charles Dickens: David Copperfield (1850)

Sometimes a small chest of books would arrive in our Achill Island home, delivered (if I remember correctly) by Castlebar Public Library, some forty miles away. Can this have been common practice at the time (early 1960s)? Its contents would have been carefully vetted by my mother, her eyes forever peeled for literary occasions of sin. From this treasure trove I was allowed to extract Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield, a hardback edition that I’ve never seen subsequently, and of which I’ve been unable to find an online image (perhaps the brown cover was supplied by the library?). I was completely enthralled by the book, but particularly by one brief passage: the runaway David’s encounter with ‘a dreadful old man to look at, in a filthy flannel waistcoat, and smelling terribly of rum’ who greets him, ‘in a fierce, monotonous whine’, with the memorable words ‘’Oh, my eyes and limbs, what do you want? Oh, my lungs and liver, what do you want? Oh, goroo, goroo!’’ If it’s characteristic of a child to fasten on to details that are marginal within the overall framework of a book, then perhaps my reading habits have retained a certain childishness.

- P. G. Wodehouse: Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves (Simon and Schuster, 1963)

Later, in Belvedere (a Jesuit school I attended in Dublin between 1964-7), I borrowed every available P. G. Wodehouse novel from the college library, a musty room that seemed to have retained the odours of generations of schoolboys. In my memory these books have blended into one inchoate but sparkling meta-book, full of ditzy aunts, cheery pigs, stammering fops, and improbable intrigues.

The very English nature of these last two choices should be noted, something that may not have delighted my theoretically Anglophobic parents, although my mother was addicted to Shakespeare, the romantic poets and Agatha Christie. Worse still would have been my enthusiasm for W. E. Johns’s novels about the gallant RAF pilot James Bigglesworth, known as Biggles, had it not been so tepid and short-lived. The fact that such things were to be found in Belvedere’s library was not unlinked to that school’s dedication to such imperial sports as cricket and rugby.

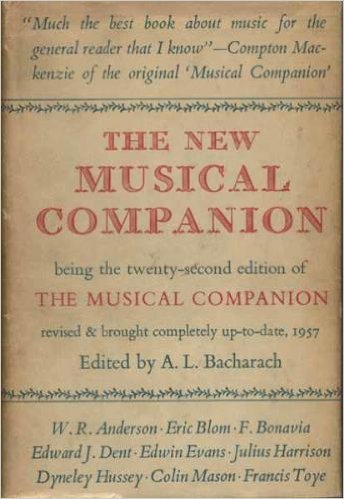

- The New Musical Companion (Gollancz, 1964 [22nd ed.])

Also very English was the New Musical Companion edited by A. L. Bacharach, presented to me in 1965 by the music-loving Fr. Murphy, Prefect of Studies of Belvedere Junior School, in honour of my year spent as school organist. The views put forward by the contributors to this compendium – Bacharach himself, Edward J. Dent, Eric Blom, etc., – were stolid in the extreme. Sibelius and Nielsen were supreme, but such British symphonists as Arnold Bax and Edmund Rubbra weren’t far behind them; the ‘twelve-note school’ was mentioned in passing and the likes of Messiaen and Boulez merited the merest sniff or two.

Nonetheless, I soaked up a great deal of information from the book, and the process of emancipating myself from it was an indispensable aspect of my musical maturation.

- Stravinsky in Conversation with Robert Craft (Pelican, 1961)

In or around 1966, when I was 13, my sister Patricia borrowed Robert Craft’s first collection of conversations with Igor Stravinsky from the library of her school, Loreto College on Stephen’s Green (Dublin). I appropriated it at once and practically memorised it – indeed I’m not sure that it ever found its way back to Loreto. While I disagreed with Stravinsky’s dismissal of my already beloved Scriabin (‘One is only influenced by what one loves, and I could never love a note of his bombastic music’ – in his early years Stravinsky was clearly influenced by Scriabin whose music is by no means all bombastic), the remainder of his strongly-expressed views became my views for several years.

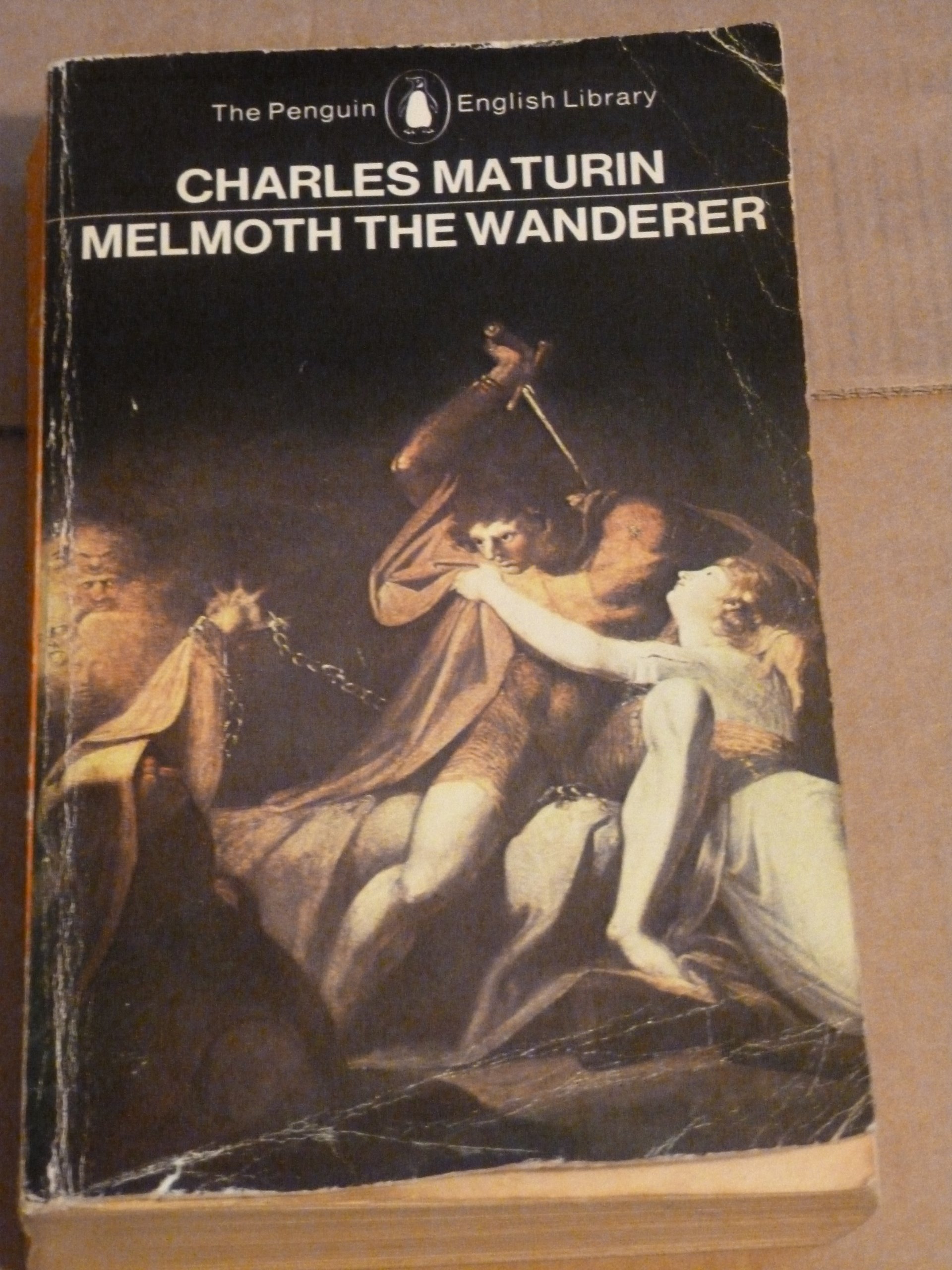

- Charles Maturin: Melmoth the Wanderer (Penguin, 1977)

Over a decade later I encountered what I still regard as one of the most remarkable Irish novels ever written: Melmoth the Wanderer, published in 1820 by the eccentric Dublin cleric Charles Maturin.

This work, an elaborate variation on the Faust theme, had a subterranean influence on French fiction throughout the nineteenth century. It inspired Victor Hugo’s early novel Hans d’islande (1823). In 1835 Balzac published a rather mediocre sequel called Melmoth Reconciled. Baudelaire loved it and thought of translating it. I’m convinced that the gloomy and mercurial character John Melmoth was reincarnated as Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo (and, in England, perhaps as Augustus Melmotte in Trollope’s The Way We Live Now). In Ireland, however, the book and author alike are almost completely unknown – although Oscar Wilde, Maturin’s grand-nephew, donned the name Sebastian Melmoth during his final years of exile. And yet, in its fragmentation, linguistic playfulness and gothic weirdness Melmoth is surely a landmark in the radical tradition of Irish writing that would flower with Joyce, Beckett, and Flann O’Brien. In the late 1970s I was preoccupied with the idea of turning it into an opera, and even drafted a libretto for what would have been a very, very long piece… It never happened, or hasn’t happened yet.

- David Lloyd: Nationalism and Minor Literature (California UP, 1987)

A few years later I was living in the German city of Oldenburg, and had joined its central public library. In my browsing I encountered a book of essays by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, of whom I’d never heard at the time. A decade later (the years accelerate with age) the Irish critic and poet David Lloyd’s Nationalism and Minor Literature (1987) was recommended to me as being relevant to something that I was writing at the time (I think it was the 2005 essay Exploding the Continuum). Already out of print, the book was unavailable at any but the most exorbitant price, but a little research located a copy in Pembroke St. Public Library, Ballsbridge. The book takes up Deleuze’s concept of minor literature, which had featured strongly in the German essay collection. Lloyd applied the notion to the 19th century Irish poet James Clarence Mangan, reading his resistance to the imposed cultural norms of a “major” nation (Britain) as a form of implicit political resistance. Apart from supplying me with some useful and suggestive concepts, the book reintroduced me to a poet whom I hadn’t previously taken seriously, and whose extraordinary poem Siberia would become the basis of my 5th String Quartet (2014).

Thus two public libraries in two European countries contributed to a constellation of reading that, for me, was productive on both literary and musical levels.