This Reading Life: Trevor Joyce

For each of the seven days of National Library Week 2015 the River-side blog will host responses from a group of seven contributors who were asked to nominate seven ‘formative’ books. The project is curated by Fergal Gaynor. Today’s contributor is poet Trevor Joyce.

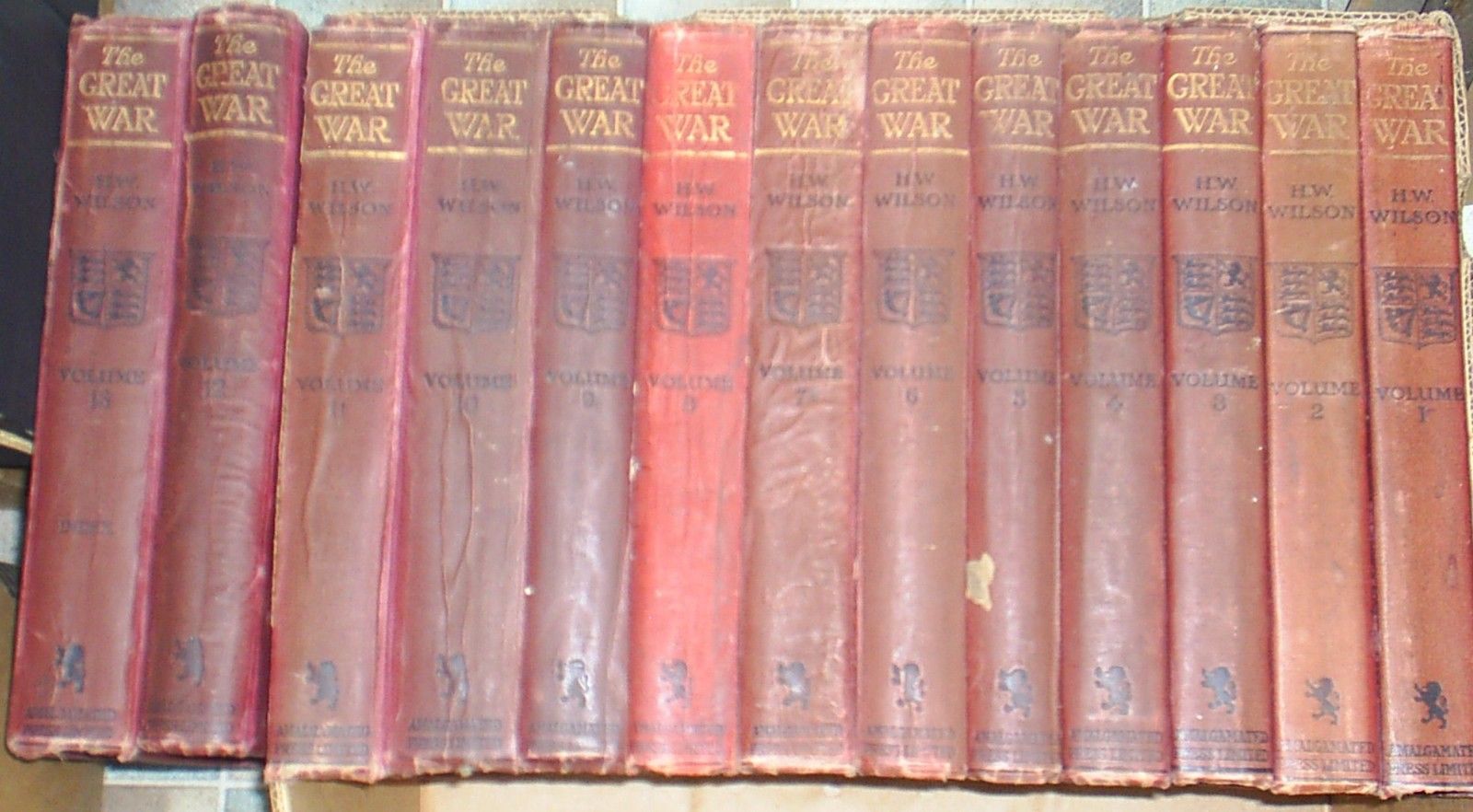

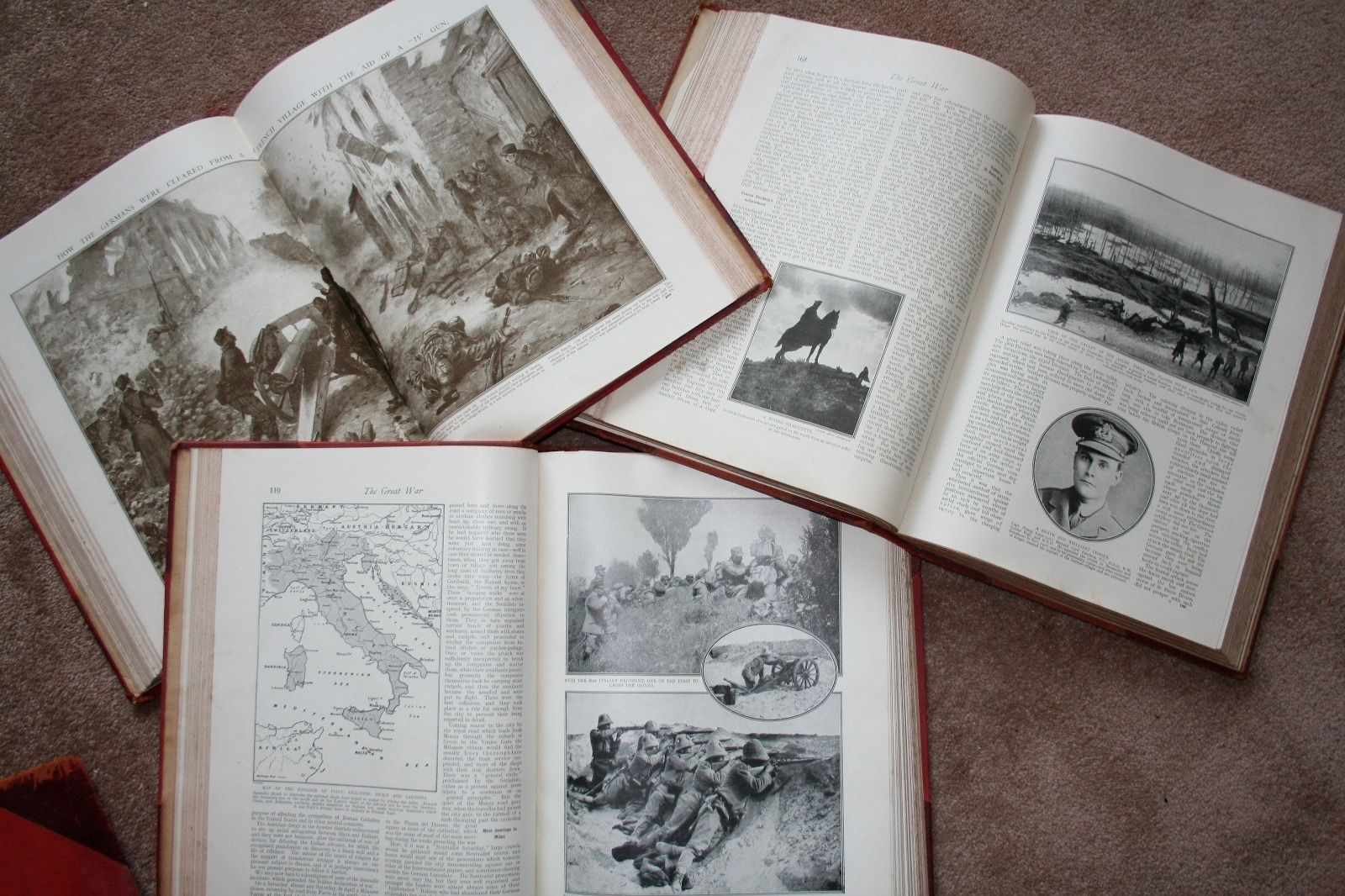

- The Great War (Amalgamated Press Ltd., 1914-1919)

I must have been about six or seven, I’d guess, when my father proudly brought home a set of thirteen very heavy books, all impressively bound in a sort or orangey maroon with gold lettering, and lots and lots of pages.

He’d spent WW I in the British Army, serving on the Western Front, and was obviously still haunted by it. I recall, when I was very young, climbing into bed with him some afternoon — he was probably trying to sleep off a hangover from the previous night, a Friday, I’d now assume — and asking him to tell me a story. He did. Several stories, in fact, but they all took place in a chaos of mud and explosions and the dismembered corpses of friends. I began to have nightmares, and never asked him again.

But these new books he brought home seemed utterly different, even though they were prominently named “A History of the Great War.” They were, fittingly, uniform, and looked very official and authoritative and, above all, orderly. He was never a great reader, and seemed quickly to lose interest in them himself, so I began to filch volumes to read when he wasn’t about.

I was soon engrossed in the strangeness of the whole thing, quite unlike any books I’d ever spent time over before. There were long tedious accounts of events and encounters I didn’t understand, from which I cherry-picked the occasional fact or phrase which did make sense, and tried from that small seed to regenerate the whole thing in terms I already knew. The photographs were the most accessible element, but though the layout was often interesting, the images themselves were oddly washed out, within only a few clear details, which looked as though they’d been picked out with a pencil. The maps were wonderful, complex with strange notations, and entirely impenetrable to me.

One weekend there was a flurry of excitement in our small top-floor flat. Someone, I gathered, was expected to call, but my parents wanted to avoid them. A debt-collector? An unwelcome cousin? I’ve no idea, but they dressed themselves and my elder sister, and left the flat for a few hours. I had been ill with some sort of a mild fever, so I was left behind in bed, with strict instructions on no account to make a noise or answer the door if anyone came up the stairs.

I had beside me the entire thirteen volumes of The Great War, and was quickly immersed again in new sections of it. Suddenly, I came across an image I’d not noticed before. It showed a human figure outside the shell of a cottage, holding aloft something small and dark. The captioned explained that this was a French farmer who had returned to his home to find it destroyed by a shell, and he was holding up the only trace that remained of them, the heel-bone of one of his daughters. I quickly shut the book and tried to find another, less awful image. I began to hear, or to imagine I heard, footsteps mounting the stairs to our door, and I willed myself to stay silent. The page in front of me showed a huge building, over which loomed the unmistakable shape of a Zeppelin. Then I noticed that in the lit windows of the building, flames were flickering. I struggled to get away, but was held down by the weight of thirteen volumes. That was the first of only two times in my life when I fainted.

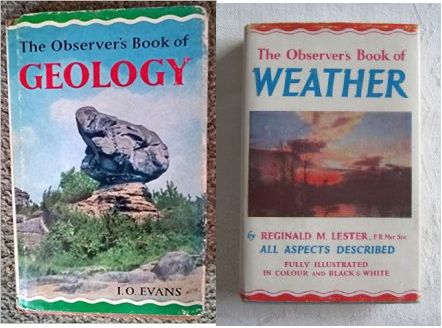

- Observer’s Books – Weather & Geology (Frederick Warne, New York, 1955)

These were two books I asked for one Christmas, and as I was lucky enough to get both of them, they fused together in my head in such a way that I’ve always thought of rocks and clouds as being pretty much identical ever since, whether boiling and erupting in violent storms, or stratifying and settling grey and immobile for lengthy periods. In later years I must have read most of the Observer’s series, which was a quick way to become a know-it-all in many subject areas, but weather and stone caught me early enough not simply to trigger information and classification, but to become an intimate part of the way I think and imagine.

- Willis Barnstone: Modern European Poetry (Bantam, 1966)

Soon after I started reading modern poetry, I picked up a used copy of J.M. Cohen’s Poetry of This Age. It was a real eye-opener so far as it went, but since it often gave only one poem per poet, it could frequently just be tantalising. Luckily, within another few months I came across this six-hundred page anthology of Modern European Poetry from Bantam, and it provided poems in plenty by most of the figures mentioned by Cohen.

It was divided into six sections, for French, German, Greek, Italian, Russian, and Spanish poetry. For most of these a variety of translators was used, but all the Spanish was translated by Angel Flores, and all the Russian by the Irish poet (and publisher of Beckett’s Echo’s Bones), George Reavey. There was a general introduction to each section, and a page or two of biography for each individual poet.

With this in my pocket, I had a way out of the narrowness of the local Anglophone poetry world, and I pretty much moved out for good. This was my introduction to Apollinaire and the French Surrealists, to Brecht and Celan and Bachmann, to Ritsos, Ungaretti, and Blok. It also gave Mike Smith and myself the additional poems we needed to confirm to us that the glimpse of wonders the Cohen book had suggested under the names Trakl and Vallejo was no illusion. In retrospect, I can see omissions, particularly of women poets and those in minority languages, but the gesture is unmistakeable, and it’s broad and generous.

I always find it odd when critics describe my own poetry as modernist, with or without some qualifying prefix. Add in Joyce, Beckett, and the great classical poets of China, and whether I fail or succeed, this is the company for whom and among whom I imagine myself as writing.

- Frederico Garcia Lorca: The Tamarit Poems (translated by Michael Smith)

Back about 1990 I took a few days autumn holiday near Ballyferiter on the Dingle peninsula. Despite feeling that poetry was, in some sense, how I could best make sense of, and in, the world, I had written only three poems since the mid-seventies that I was even half-way satisfied with, and felt that my way back to poetry was blocked by my antipathy to most of what was increasingly filling the book-shops and the review sections of newspapers.

I had brought with me on that trip just a few books, to prime the pump, as it were, including the little Penguin volume of Lorca’s poetry, with prose translations by J.L. Gili at the foot of each page. I had never been too keen on Lorca’s Gypsy Ballads, but towards the back of this book I found a few lyrics from the new collection he had just finished when he was murdered. One of them in particular, ‘The Casida of the Weeping’, resonated strongly with what I was myself trying to work through at that time, and suddenly, I found that the notes I was writing seemed recognizably to be forming a poem. I ended up that day with the poem, Strands, which later became part of my first published book in almost twenty years.

As soon as I got back to Cork, I phoned Mike Smith, who was always alert for things to translate, particularly from the Spanish. I kept on and on at him about how important this particular volume of Lorca’s was, and how there were none of the stock figures of the Gypsy Ballads floating around, but instead what I could only describe as a sort of ‘poetic algebra’, a symbolic language that permitted the expression and manipulation, with great grace and speed, of highly complex feelings and ideas. I suspect Mike remained sceptical of my high-falutin account, but the poems themselves convinced him.

Over the following months Mike translated and sent me drafts, and I adjusted or commented on them, while continuing to develop the mode I’d started in Dingle, which I hoped might reach some way towards paralleling Lorca’s ‘algebra’. It took another four years till my stone floods was completed, and Mike’s version of Lorca’s The Tamarit Poems didn’t appear till 2002, but I always like to think of them as twin volumes, trying in analogous ways to load the language up, and make it sing. An exploratory, quizzical, and occasionally plangent duet.

(For more on poet and translator Michael Smith, see http://aosdana.artscouncil.ie/Members/Literature/Smith.aspx)

- David Coxe Cooke: Famous Fighting Indians (Transworld, 1956)

There’s one particular knot of books I learned a lot from, but I can’t honestly remember which of them came first, or made the biggest impact. We had very few books in the flat when I started reading. Mainly they were grim 19th century volumes in dark binding, that I steered clear of for many years. I don’t think anyone else read them either, and I suspect they were there for show. One resource I did have, though, was an older sister. She was nearly four years older than me, and was already a voracious reader. She had very specific tastes and interest, though, and that’s what got my attention. In particular, she was fascinated by Native American culture and history, so that when a group of us kids were arguing whether John Wayne or Jimmy Stewart was the more deadly shot, she’d always side with the Indians against the cowboys.

She seemed to spend most of her pocket-money on books about them, and carried on a very adult correspondence with the U.S. Department of Indian Affairs, who sent her very impressive coloured magazines about how good life was on the reservations. I think I was just puzzled at first by what seemed, in the context of my childhood, very odd behaviour, but I was intrigued, and soon found myself following in her footsteps, reading her books whenever she put them down, and trying hard to understand the very alien world described in them.

There were two in particular whose names I remember. Death on the Prairie was a very worthy, but to me, aged eight or nine, slightly dull volume. I think I recall her buying it for ten shillings. The other book, which more immediately suited to my tastes, was a pulp paperback with a garish cover, called Famous Fighting Indians. As the author, David Coxe Cooke, also seems to have written on Fighter Planes That Made History, The Tribal People of Thailand, and on how to improve one’s baseball skills (thank you, Google), I gather he was more of an all-round jobbing writer than any sort of a specialist, which might explain why I can’t find any image of the cover online.

It was in that book that I first encountered Chiefs Roman Nose, Black Kettle, and Alligator-Stands-Up, and came to admire Chief Joseph and the long retreat of the Nez Perce. I’m sure, in retrospect, that it was full of orientalising clichés, but it made a space which allowed me later to think about other ‘exotic’ peoples and cultures, and recognize how, often, their worlds were being threatened and destroyed by mine. Knowledge of the Sand Creek Massacre is still a very useful tool for understanding the ‘developed’ world and its doings.

- Barbara Ehrenreich: Dancing in the Streets (Granta, 2007)

In the last couple of years, I’ve found myself making space on my shelves for a new category of books: ones that are aware of the corruption and repressiveness of capitalism and the cynicism of its attendant real-politik, but that contrive somehow to resist and see past it all.

Among these, I’d put David Graeber’s big history of Debt: The First 5000 Years and, very prominently, a whole bunch of Rebecca Solnit’s books. But there’s one in particular I find myself returning to, and using to think with when I need a jolt of energy and good cheer: Barbara Ehrenreich’s Dancing in the Streets, subtitled A History of Collective Joy. It’s part history, part anthropology, with a little dose of activism, and it ranges from Greek mystery cults through the Puritans and Fascists, to organized sports and rock ‘n’ roll.

- A.C. Graham: Poems of the Late T’ang (Penguin, 1968)

One of the problems of having a large library is that, one way or another, you lose a lot of books. Mice, leaking pipes, and the penetrating Irish damp have all played merry hell with my collection, but the biggest danger has always come from fellow readers. For me, it’s always been a major part of the camaraderie of reading that, if you find something that really engages and excites you, you try to pass on that pleasure by recommending that book to others and, most likely, underlining the point by loaning it.

The single volume that I’ve bought most often — probably over twenty times in all — and lost by either loaning, or simply giving away, is Angus Graham’s Poems of the Late T’ang. I picked up a copy in the late sixties, having no idea what sort of poetry I might find in it, and not even being able to make sense of the title. Books were so cheap then, that even if you were unemployed or in a low paid job, you could still afford to buy the occasional one.

The T’ang was perhaps the greatest of the Chinese dynasties, lasting from 618 to 907 C.E. About mid-way through, in 755, the An Lushan Rebellion brought on civil war and mass-disturbances that almost wrecked the empire. Suddenly, all changed, and in place of the bright, self-confident poetry of the High T’ang, the poetry written after the rebellion, in the late T’ang, tends to be very dark (in several senses) and difficult, and full of trepidation and inwardness.

Graham summarises not only this historical context in his introduction, but also gives an excellent potted survey of the history of translation of Chinese poetry into English. This supportive material extends throughout the book in the form of notes, sometimes quite extensive, on the poems. But the glory of the book is in the translations themselves, which bring over these artefacts of a very different culture, and make them into wonderful poetry in English, as fully at home as FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat, or even the King James Bible.

I gather that Roger Waters of Pink Floyd took some lines from this book for his songs ‘Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun’ and ‘Cirrus Minor’, and I’m not surprised. The poetry of Li Ho, Li Shang-yin and the late work of Tu Fu, in particular, is like nothing else I know, in the strangeness of its images, and the complexity of its language, even in Graham’s translation. Go borrow a copy.

(This volume is no longer in print from Penguin, but happily NYRB have republished it.)

7b. Patrick Galvin: New and Selected Poems (Cork University Press, 1996)

The annual SoundEye Festival in Cork got started almost by accident, as a one-off, and has survived, I think, only because of the intense pleasure it has at times given to myself, and to the others who now organize it. It’s been a window out onto the wider world of contemporary poetry; one through which we get to know what’s happening abroad in ways the arts pages of the newspapers will only catch on to years later, if ever.

It’s been a great gift, and an education, to watch younger poets develop their strengths at successive festivals, each it seems, taking their energy and example from a different poet visiting from Britain, the USA, Australia, or elsewhere. For me, though, the most sustained incentive has been to hear the work of fine poets, working at the height of their powers. Through SoundEye, I’ve got to know the poetry of Susan and Fanny Howe, of Nathaniel Mackey, Maggie O’Sullivan, Tom Raworth, and Peter Manson, and I wouldn’t be without any of those.

Looking back, though, I think the greatest impact on me was made not by a visiting poet, but by a native of the old City of Cork itself, Patrick Galvin. I was introduced to Paddy’s work back around ’72 by Mike Smith, and around that time we became, through New Writers’ Press, the first Irish publishers to bring out a volume of his poetry, The Wood Burners. Around then, also, I met Paddy for the first time, at a reading the three of us did together in Cork. It was so enjoyable a night that Mike’s car ran out of petrol on the way back to Dublin, and I spent the early hours cursing and shivering, with the gear-lever lodged uncomfortably near my kidneys.

Paddy’s New and Selected Poems came out in ’96, and it was from that he read on the one occasion he performed at SoundEye. It’s a worthy attempt at representing his poetry, though there are curious omissions, such as the title poem from his first collection, Heart of Grace. It’s a book I’ve always kept near me these last fifteen years, and particularly since Paddy’s death in 2011. There’s a sore need of a properly researched and edited Collected Poems for Paddy, but for the moment, this must do.

It reminds me often of Lorca, especially how it resonates with folksong, and also of Neruda, Hikmet, and the other great poets of resistance and of ordinary life from the last century. In the end, though, the force ringing through the lines is Paddy’s own, unmistakably.

Someone wears a royal crown

Kings and Queens march on the town /

And the old ones in the street

Ring the dead bell of defeat. /

Reason bleeding through the snow

Nowhere else on earth to go. /

Mother of God be our relief,

Close the world on all our grief.