This Reading Life: Judy Kravis

For each of the seven days of National Library Week 2015 the River-side blog will host responses from a group of seven contributors who were asked to nominate seven ‘formative’ books. The project is curated by Fergal Gaynor. Today’s contributor is writer and publisher Judy Kravis.

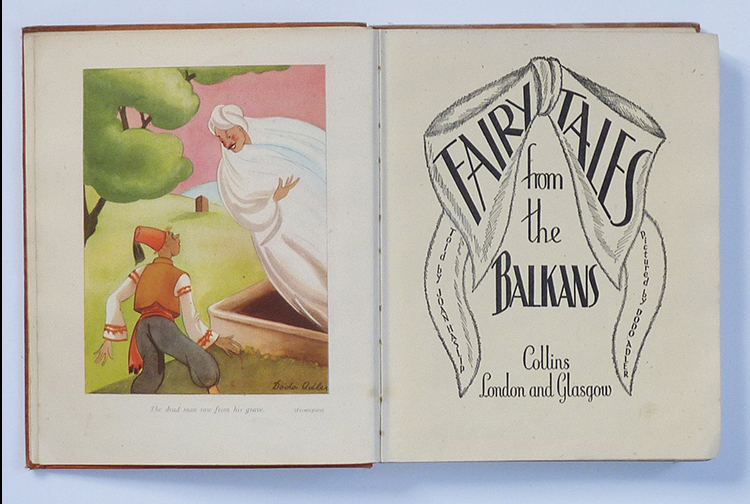

- Fairy Tales from the Balkans (Collins, 1943)

A Christmas present when I was maybe six, secondhand with soft orange cloth cover — it was OK to give presents that were secondhand, then — and my first reading challenge: a book based on text not on pictures. The stories rapidly formed a substrate of my imagination and my fear, such that a pair of birch trees outside my window today always recalls one story in which golden-haired twins are buried alive by a wicked mother-in-law and two trees spring up to mark the spot.

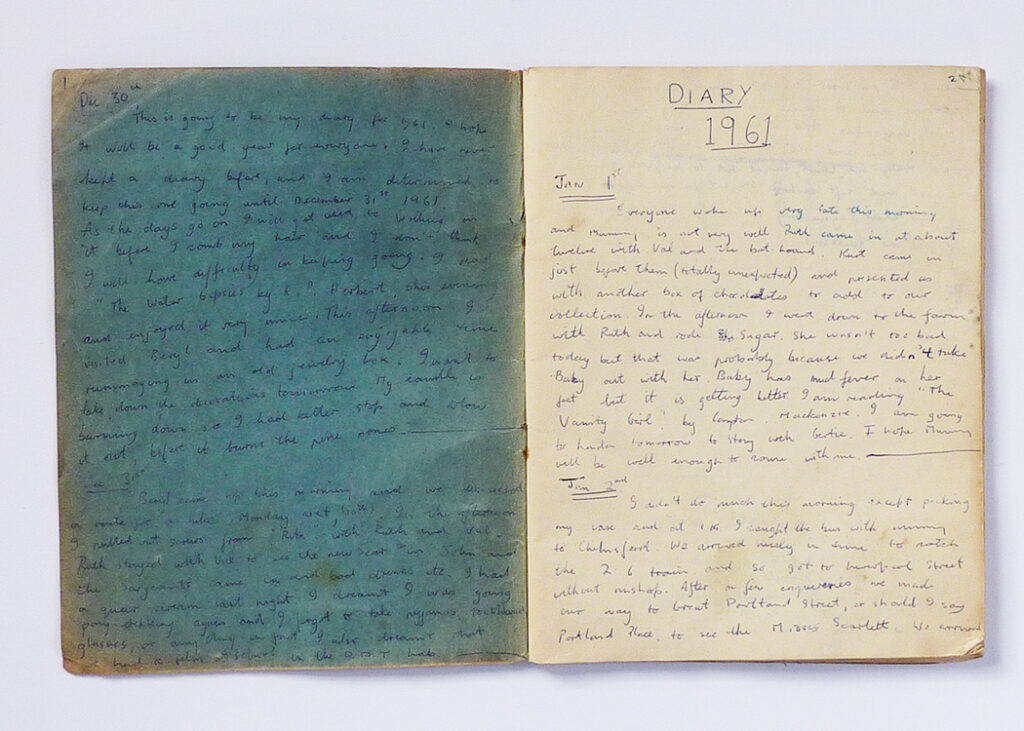

- Volume 1 of my Diary

An exercise book with thick smooth paper that I bought to honour a biro I’d been given , as well as my timely adolescent reading of The Diary of Anne Frank: this was the start of a very long shelf and represents an addiction unlike any other. First of all a writing book, then rapidly a book I read and reread in order to find the person I was creating and be reassured.

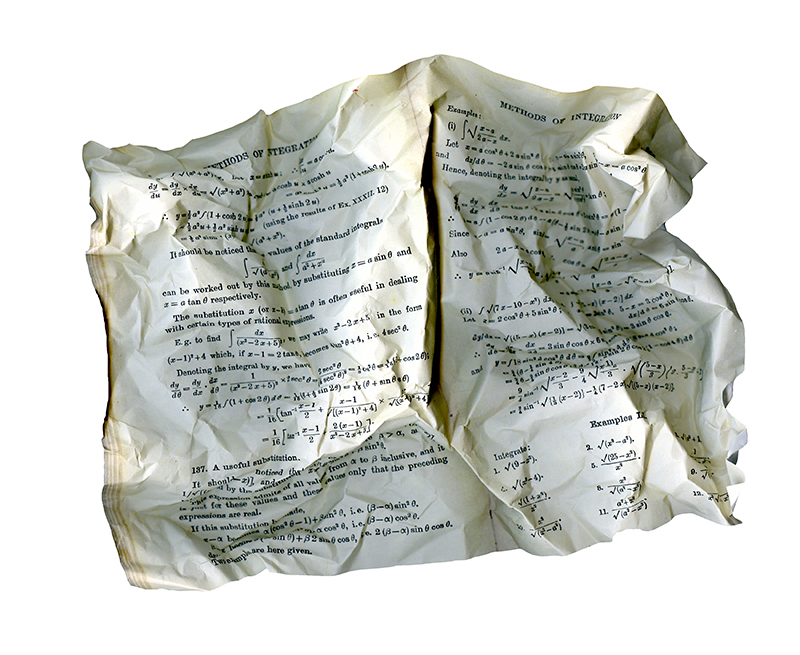

- G.W. Caunt: An Introduction to Infinitesimal Calculus (Oxford, 1914)

A sturdy book with a dark blue/green cloth cover, part of my father’s small collection of books from his late (interrupted by WW2) and unfinished study of engineering. I never opened it, but the title registered, especially the word ‘infinitesimal’, every time I walked past it on the shelves.

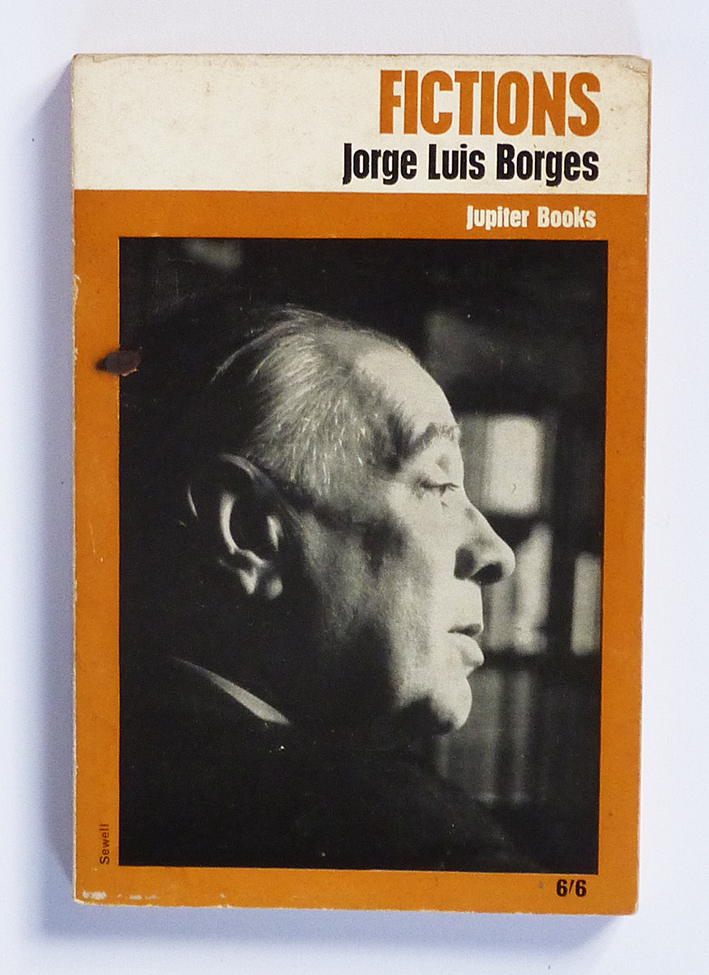

- Borges: Fictions (A Jupiter Book, Calder, 1965)

Recommended by a friend when I was about 22, and the first book I read in the same way I ate dessert as a child, slowly, wanting there always to be some left. As indeed there would be for years. Borges confirmed my taste for books I couldn’t entirely understand: circularity, the infinite, words/letters as indecipherable, a language perhaps known only to the gods, as in Homer.

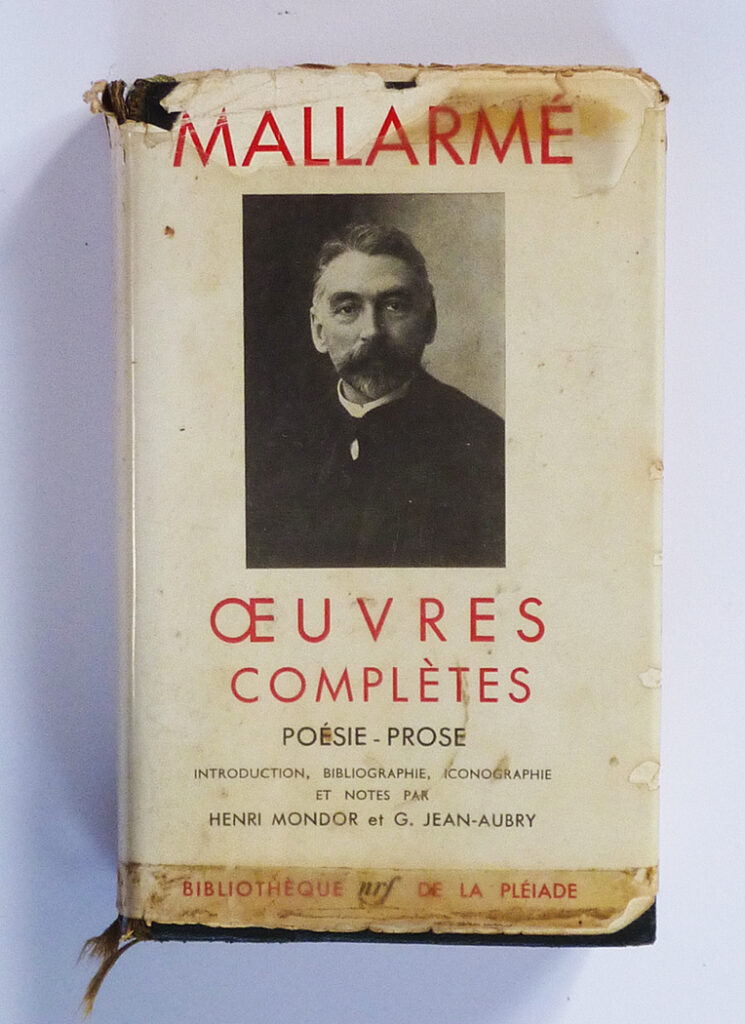

- Mallarmé: Oeuvres Complètes (Nouvelle Revue Française, 1945)

A Pléiade edition I read so exhaustively for my PhD that some of the fine India paper pages loosened. It was a privilege, an intimacy beyond most others, to know so many thin pages so well, to get to the heart of difficulty and stay there. Many years later, I couldn’t open it without wanting to burst into tears, especially if listening to Schubert at the same time.

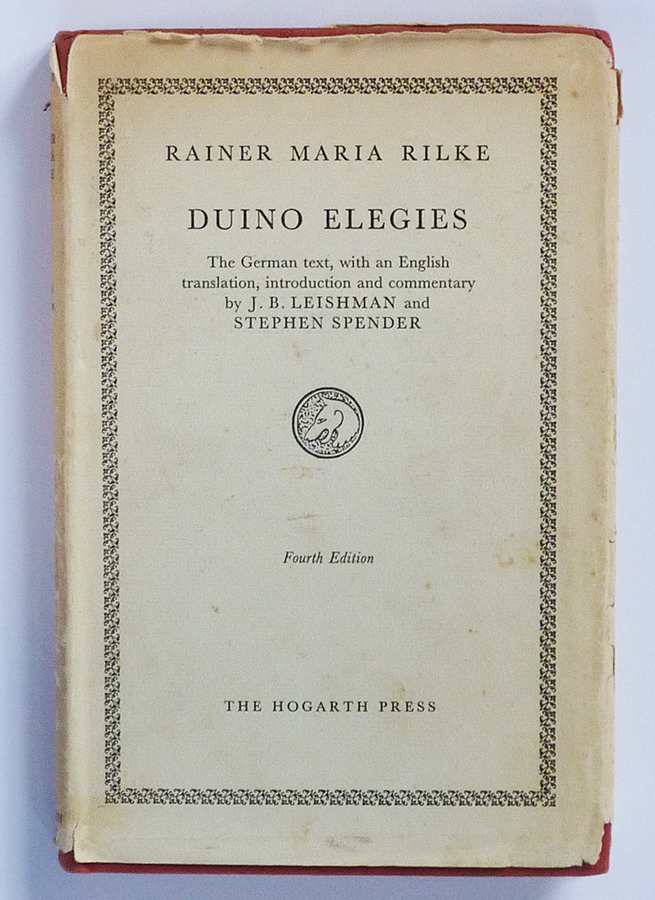

- Rilke: The Duino Elegies (The Hogarth Press, 1939)

I read the English then the German, whose relative unfamiliarity and shorter music confirmed that another’s words could correspond to my deepest fears/desires and convert them into a breathless pleasure. ‘Nowhere, beloved, can world exist but within.’

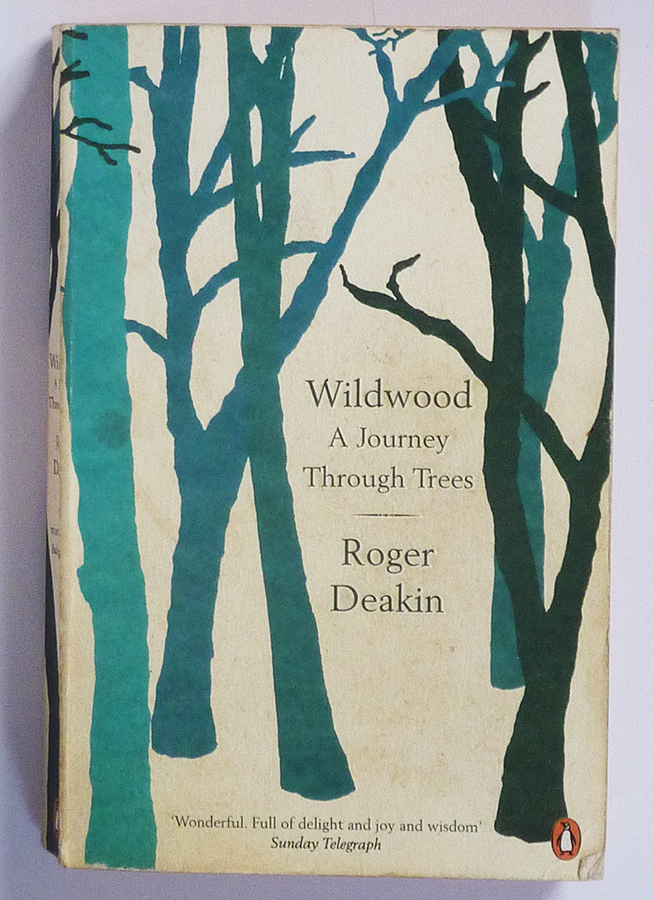

- Roger Deakin: Wildwood (Penguin, 2008)

Nowhere, beloved, can world exist but without: among the apple trees of Kazakhstan and the walnut woods of Uzbekistan. This is the centre of the world as I construe it, corresponding both to the geography of Fairy Tales from the Balkans – whose most splendid princess, the Tzarevna Loveliness Inexhaustible, lived beyond the lands of Thrice Nine in the empire of Thrice Ten, which was surely in the direction of Central Asia – and to much later concerns with ecology and environment.